Please note that this summary was posted more than 5 years ago. More recent research findings may have been published.

Summary

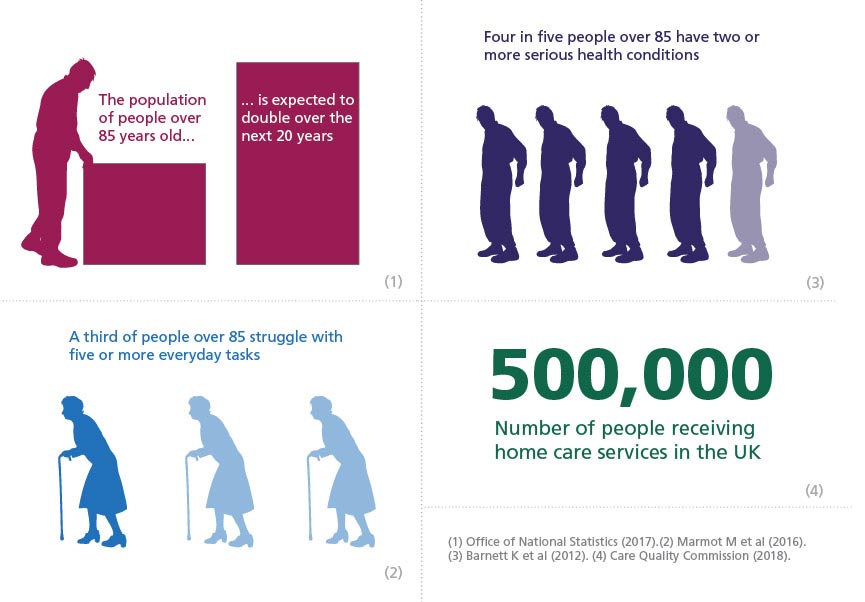

More people are living longer with complex conditions and needs. Technology can help people to stay living well and safely at home as they get older. But technology is changing rapidly and it can be challenging to get the right technology for the right person with the right support. There has been considerable investment recently in developing and evaluating assistive technologies for older people. But this is a relatively new field and there are important gaps in what we know.

This review presents a selection of recent research on assistive technology for older people funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and other government funders. This has been selected with help from an expert steering group. In this review we focus on research around the use of technology in the home, remote monitoring systems and designing better environments for older people.

Using technology

We need to understand more about how technology is used by older people in their home. We know that many devices are never used and more are not used fully or as intended. Research helps to understand the reasons for this. Insights include the timing of introducing new technology – often too late, at the point of crisis or advanced illness. The health of older people is often unpredictable and demands of technology may be too much at times. Research also shows real ways in which people use devices and services, including workarounds and adaptations. Under-investment in training to support longer term use of technologies in the home is an issue, and the human element of support is essential. Studies also highlight the need to motivate staff such as community nurses in the benefits of telecare and other initiatives. Based on research, a toolkit has been developed to guide those designing and implementing telecare systems.

Remote monitoring

A number of studies have explored integrated monitoring and response systems to check the health, wellbeing and safety of older people living at home. Some of these are focused on particular groups, like those with dementia. They range from systems using sensors, alarms or wearable technology to cameras, smart televisions and service robots. Some collect data on health status, movement or eating and drinking. Other systems are more interactive. A selection of studies also looks at the use of home technology, from telephone to social networking devices, to combat social isolation in older people. Much of the research to date has focused on developing prototypes and systems. There is little real-life testing or evaluations showing impact on falls, hospital admissions or quality of life.

Designing better environments

Occupational therapists play a crucial role in assessing the home and adapting the environment for older people. Research includes developing smart solutions for bathrooms, where many falls happen. There is also research to inform design of future kitchens to make it easier to cook with limited function. Other studies have focused on the wider neighbourhood, with teams involving clinical and public health researchers working with engineering, housing, architects and urban planning experts. These include better design for those with mobility issues or confusion. There has also been more basic research, for instance on navigation issues for people with dementia, which should inform design of future homes and care homes.

Future directions

This review gives a flavour of recent research which has tested and developed technology to help older people live longer at home. There are challenges in doing this research, from recruiting older people into studies to the rapid pace at which technologies change. Research has focused more on high-end digital technology than evaluation of more basic devices to help toileting, mobility, vision and everyday tasks. In terms of systems and technologies featured in this report, there has been more research effort in developing prototypes than real-world testing in the home. Little is known about actual use of technologies over time and their impact in preventing falls, reducing isolation, or anticipating health crises or emergencies. More research is needed using mixed methods to evaluate technologies in use and share learning across sectors.

Introduction

Why is assistive technology important for older people?

More people are living longer, but with complex needs which require more health and social care resource. At the same time, people want to stay in their own homes as long as possible. It is in everyone’s interests to find ways to support people living well and independently at home. Assistive technology can play a part in this, helping people to manage complex health conditions and to live with dignity at home while staying connected to others. The right technology solution may also help family carers to support a person’s everyday activities around the house. In this way, it can help to reduce the risk of unplanned hospital admissions or permanent moves into residential care. National strategy underlines the importance for the health and care system as a whole of keeping older people with mild frailty healthy and socially active. Different forms of assistive technology in the home can help in achieving these goals – ageing well in place.

Since 2014, there are also new formal responsibilities for local authorities based on the Care Act in England and the Social Services and Wellbeing (Wales) Act. There is a requirement to provide care and support for those older and disabled people who meet their eligibility criteria, to prevent deterioration and reduce demands on other services. Meeting these needs includes adaptations to the home and provision of technologies.

What is assistive technology?

There are many different terms to describe technology used to support the care of older people. Common terms include telehealth, digital health and telemedicine, all with particular meanings. Assistive technology covers anything which helps people stay independent, manage their health or compensate for a disability. This includes everyday aids like walking frames or wheelchairs to more advanced digital technology like robots and the internet of things (where everyday household appliances and devices ‘talk to’ each other). Assistive technology is also under the control of those individuals themselves and so does not include implants or other embedded devices. This report, though, does include telecare and telehealth systems, where health professionals may respond at a distance to data collected from sensors, such as motion detectors or wearable devices monitoring heart rate, or to people activating alarms within the home.

What is the purpose of this review?

This review provides a selection of recently published research funded by the NIHR and other government funders related to the use of assistive technology to help older people live independently at home. A number of research projects are highlighted which should be of particular interest to those delivering, planning or using adult health and social care services. These have been identified with input from an expert group of relevant stakeholders listed under Acknowledgements. Our approach to identifying and selecting relevant studies is given in the Search strategies section.

Related links:

- A more complete inventory of all research on assistive technology funded by the UK government.

- NIHR themed reviews are available on related areas such as care homes, stroke and frailty.

Understanding technology in use

It is well known that much technology to help older people in the home is abandoned or not well used. Some research has suggested that as much as 40% is never used (Federici 2016). Research can help us to understand more about individual preferences and needs and the ways in which devices are integrated (or not) into everyday habits and routines.

Not just the device

We know that making technology useful and ensuring it is used needs an understanding of the individual and the wider context in which services are delivered. This includes the role of the family, the occupational therapist, social worker, community nurse, homecare support or voluntary sector staff working with older adults. Some research studies have looked at how technologies are used – or not used – by older people and the way in which they are supported. Without this understanding, technology will not realise its potential to enable older people to live well for longer at home.

Older people may have concerns that technology might be used to replace face to face care. This was one finding from an international study in four countries, including the UK, which used citizen panels and observational research to explore ethical and social dimensions of telecare systems for older people. Researchers noted that installation was often wrongly seen as a one-off event, rather than an ongoing process for getting the best out of the technology. Overall, this study found that users of telecare often struggle to understand and engage with the technology in their homes. An important insight was that “telecare does not perform care on its own.” Telecare systems require human input and understanding of the older person and their needs. Most depend on existing networks, including family carers and volunteers. Researchers engaged in this initiative suggested principles for more ethical telecare development. These included greater involvement of service users and carers with on-site evolution and adaptation of technology in the home, rather than one-off installation. (Study 1)

Silver surfers?

The benefits of everyday internet-enabled technology are not shared equally across all age groups. Of the 10% of people in the UK who have never used the internet, four out of five are over 65 years old. But this is changing – for instance, latest figures show that tablet use has increased from 15% in 2016 to 27% in 2018 in the over-75 year age group (Ofcom 2018). Overall though there are risks of digital exclusion for older people and we need to factor this into new developments.

Realities of using technology

Sometimes it is not clear whose job it is to provide ongoing support for older people using technology. A qualitative study of people with dementia, carers and GPs on the use of assistive technology generated some useful insights. Participants were using devices such as GPS tracking systems, community alarms and reminiscence tools. Doctors often did not feel well informed about the availability of technology and noted a lack of clarity about who was responsible for issues like responding to alarms, maintaining systems and training users. The role of the voluntary sector was mentioned, for instance for patients and carers to try out new devices at dementia cafes and peer support groups. (Study 2)

One NIHR study (Study 3) aimed to identify design principles for effective technology solutions in the home. This research combined interviews with technology providers and service staff, together with observational research to understand how people living with multiple illnesses use and experience technology in their everyday lives. This generated useful insights into the nature of living with complex illnesses which may be unpredictable, the demands of using technologies, and the workarounds and pragmatic approaches of individuals to these challenges. Many of the installed assistive technologies did not meet user needs and had been abandoned or disabled. ‘Off the shelf’ devices were rarely useful to the individual, but needed to be adapted or customised – in a process that researchers called ‘bricolage’ – by carers and those who knew their daily routines and limitations. Working together, users and researchers identified some important principles for future telehealth and telecare systems.

Principles for designing telecare systems

Working together, users and researchers identified some important principles for future telehealth and telecare systems which need to be:

- ANCHORED in a shared understanding of what matters to the user

- REALISTIC about the natural history of illness

- CO-CREATIVE, evolving and adapting solutions with users

- HUMAN, supported through interpersonal relationships and social networks

- INTEGRATED through attention to mutual awareness and knowledge sharing

- EVALUATED to drive system learning and future development

(Greenhalgh 2015)

The timing of introducing devices may be important, with many informants in one study seeing it as a ‘last resort’ measure, rather than a preventative measure. This insight emerged from a qualitative research study with older people to understand why individuals might not use devices. (Study 4)

The difficulties of introducing new technologies to people at an advanced stage of impairment or distress has been identified through research. Particular devices like heat extreme and smoke detectors or gas shut-offs helped older people to cook for themselves safely at home. But not all devices were used or useful. A mixed methods study looked at the experiences of 60 frail older people using telecare in two regions over time. The study sites had both developed integrated systems linking elements such as pendant alarms and bed and chair sensors or fall detectors in the home with a community response service. Home care workers and others noted the importance of users having control and choice over the type of technology installed, but this was not always achieved. The qualitative research provided useful insights into how older people experienced the technology. Many telecare systems had been introduced following a crisis like hospitalisation and it took time to realise the benefits. One helpful insight from a human factors perspective was to ask designers of telecare systems, ’Who is this not designed for?’ and ’What do we do when this goes wrong?’ These kinds of questions were often overlooked when investing in and implementing high cost telecare systems. (Study 5)

Beyond installation

Navigating complex partnerships between agencies may be challenging and there is a need for resilience and flexibility in dealing with setbacks and change. These lessons come from 2016 research on the implementation of a large-scale telehealth programme (Study 6). This delivered a range of digital health and wellbeing technology to 169,000 people in four communities across the UK. There were sometimes constraints for commercial providers in maintaining awareness of their brand when technology was adapted and customised for local use. Approaches to product design and marketing were very different in healthcare and in digital technology. There were also often problems of interoperability and information governance in sharing health and other personal information across sectors.

Information and support is often limited for those introducing and implementing telecare systems. One study used research to develop a toolkit with practical guidance for those planning new systems. Past evidence shows that the promise of small-scale telecare pilots are often not realised at scale. This is partly because of local contextual issues which are not properly identified or anticipated. This resource uses the analogy of preparing for a race, frontloading effort in training and preparation work before the system goes live. Piloting and points for reflection are also important. This resource should be useful for managers, practitioners and technical staff. (Study 7)

Get the small things right

As a patient, I consider that getting user views is crucial in order to find out what the user really wants or needs, and hence what problems the technology is designed to solve.

The topics selected for research and development are not necessarily those that are important to the user. After I came out of hospital with a broken ankle and couldn’t move around my home easily, I realised the importance of relatively small items, such as cups with spill-proof lids and non-slip mats. Technology is only part of the solution, and the role of occupational therapists is crucial.

From my experience of diabetes-related technology, if service users do not benefit from the more advanced technology such as user-enabled remote monitoring by clinicians, the service user may decide not to use it and hence the tele-monitored data will not be available to the clinicians. For other tele-monitoring technologies, the user may decide to turn it off, with the same effect.

Brenda Riley, service user

Services and systems

The level of investment by local authorities in training for telecare assessment and use may be insignificant compared with the large sums spent on telecare devices, and much of it is provided by telecare companies. The duration of this training was also very short. These were amongst the findings of an NIHR-funded national survey of local authority adult social care managers providing telecare services. The most common devices in use were emergency pendants, fall detectors, bed and chair sensors and smoke alarms. Around a quarter of respondents estimated that use of this technology had reduced costs but found it difficult to provide hard evidence of efficiencies. A third of respondents reported that telecare investment was informed by research. Only a quarter had developed telecare strategies for older people with the NHS and other partners. This survey highlights useful ways in which planning could be more joined up and investment focused on areas of need, including staff training and ongoing support for users. (Study 8)

Attitudes of staff are important to successful implementation. Qualitative research helped to identify some important insights into the views of frontline community nursing staff using telehealth to monitor the health of older people with heart failure and lung disease in four study sites. This study indicated that staff acceptance of telehealth is a slow and fragile process. There was uncertainty about the use of technology and how it might affect the relationship between clinician and patient. Early wins and demonstrated patient benefits appeared essential to ensure buy-in. Further participatory research highlighted the ways in which changes in technology and wider services affected staff motivation and implementation success. (Study 9)

A recent review of evidence on the use of digital technology of all kinds (for remote monitoring, entertainment and care) in care home settings noted the poor quality of research overall. Existing evidence suggests that cost, ease of use and the demands placed on staff could be both barriers and facilitators to supporting use of technology by residents. (Study 10)

We are all potential consumers of technology to help us live at home in old age. One study investigated barriers and enablers to developing a consumer market in assistive technology. It found that public awareness of assistive technology was poor and concluded that the consumer market is not well-developed in the UK. Although there was a willingness to use and buy assistive technology, potential consumers could not find where to go for advice. (Study 11)

Remote monitoring

How is technology used to monitor the safety and wellbeing of older people in their homes?

The last 20 years has seen a rapid growth in the systems and technologies to monitor people at home. This may include pendant alarms linked to an emergency response centre for people in their own home or in sheltered housing. Other systems are based on collection of vital signs and health markers for those with long-term or complex conditions, with an alert when action is needed by a health professional.

A Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE) review of use of video and monitoring technology in health and social care noted that the evidence was limited (SCIE 2008). Available research highlighted potential for staff efficiencies, monitoring large numbers of people through fall sensors and other devices. But there are trade-offs and tensions between privacy and safety which have not always been fully explored. And the impact of using these technologies to help people to live longer at home is poorly evidenced.

Keeping well

There is potential for systems to help people living with chronic or disabling conditions by responding to prompts about deteriorating health or other concerns. An NIHR Cochrane review in 2015 of 41 published studies showed that technology including remote monitoring by health professionals of data like heart rate and blood pressure could reduce deaths and hospital admissions for people with heart failure. (Study 12)

Indeed, the studies focused on remote monitoring indicated a reduction in all types of death of 20% and a reduction in hospitalisation related to heart failure of 29%. This suggests potential gains for people with long-term conditions through tracking changes in health and wellbeing which might need action by a health professional.

A large NIHR trial is looking at whether a tailored telecare package, including sensors or devices like carer alerts, helps people with dementia to remain living in their own homes for longer. The study will test whether people receiving the technology are less likely to move into residential care over a five year period. (Study 13)

Another smaller NIHR study worked closely with older people with heart failure and their families to develop and adapt a monitoring system. This involved sharing data with specialist cardiology teams on medication, blood tests and clinical episodes and was found to be acceptable and practical to patients in their homes. A follow-on trial has tested further whether tailored alerts and personalised feedback to patients improve outcomes. (Study 14)

One important aspect of older people’s wellbeing is what they eat and drink. Poor nutrition and hydration is associated with many risks, from falls to delirium. But it is common for older people, particularly those living alone, to forget to eat or not eat enough. It is estimated that one in ten older people is at risk of malnutrition, particularly those living at home (Age UK 2015). One study validated a touchscreen device for older people who had not used computers before to report regularly what they were eating. This appeared easier and more acceptable than food diaries using pen and paper. Individuals also reported physical activity and mental alertness in this way, without the researcher being present. (Study 15)

Joining up devices around the home

A number of large international research collaborations over the last ten years have developed and tested integrated monitoring and response systems in older people’s homes. These have included use of interconnected home security cameras, tablets, smart televisions, sensors and wearable wristband devices to check activity levels and wellbeing. These have often ended with assessment of prototypes in laboratory conditions. Few studies have taken this further with real-life testing in the home or summative results of impact, such as preventing falls, emergencies or hospital admissions. It can also be hard to locate published and accessible outputs for research projects in this field.

Among studies which included some element of real-life testing was an integrated monitoring and communication system in demonstrator sites in the UK, Greece and Israel. There were interesting differences in laboratory and home settings – for instance, smart watches which needed charging every day were not always worn by older people at home. In both settings, smart televisions appeared unobtrusive and well accepted, but active use of the health portal through the television declined in the home without the support of a facilitator. Further work is needed to build on these preliminary findings reported piecemeal in 2015. (Study 16)

An earlier EU project reporting in 2011 combined home security, personal and environmental monitoring and communication. This was developed with older and disabled people and tested in laboratories and through a trial which included 62 users, 45 carers and 14 staff delivering home and residential care. (Study 17)

Another UK study which did real-life testing assessed a remote monitoring system in a sheltered housing complex in London (Study 18). This combined sensors to response systems with health care professionals, social workers, friends and family. It picked up problems from information collected by sensors, such as people spending an unusual length of time in the bathroom.

Other studies have included some feedback loops to develop and adapt the prototype. A large EU assistive technology project focused on the need for remote monitoring systems to be tailored to individual needs and to allow some control for the user. This included for instance decisions about number of reminders and when to escalate concern if medication was forgotten. Another feature which was adapted during development was to make the user interface more like a television remote with numbers instead of icons, as this made it easier to use. (Study 19)

Similar adaptation was seen in another study of older people connecting wearable sensors, devices in the home and mobile phones to care workers. During the study, touchscreens were made bigger so that they were easier for older people to use. Emerging findings from early prototype testing suggested good usability (Study 20).

Using robots to support care

An interesting development is the use of robots to support older people. Many of these projects are at ‘proof of concept’ or early stage research. One project looked at a wide range of uses for people with early stage dementia, including playing music, contacting friends and family, reminders of medication,tracking individuals’ movements and linking to smart devices in the home. (Study 21)

A similar project is designing robots to help older people to stand up from a chair or bed, move around and carry objects in the kitchen and elsewhere. The robot would respond to voice commands and interact with other devices and sensors in the house. Friends and family could also be kept informed of individuals’ health status and wellbeing. (Study 22)

One large research programme is focused particularly on the interactions between older people and robots in the home. Researchers are looking at how elderly people, or their carers or relatives, can make robots learn and respond to activities and sensors. (Study 23)

Keeping safe

A number of projects have focused on the particular needs of people with dementia. This includes the challenge of keeping people safe who may be confused but able to move around.

One study addressed the problem of older people with early stage dementia waking at night and being confused and disorientated. Having tracked typical patterns and risks working with people with dementia and carers in their homes, the researchers developed some prototypes. This included use of software, bed sensors and cues for light, music and other technology which could provide reassurance or alerts for response services. (Study 24)

One qualitative study of people with dementia and carers explored the acceptability of GPS tracker devices as part of a wider study to develop a new safe walking device. GPS trackers can be used to enable people with dementia to keep active by walking, without risk of wandering or getting lost and keeping others informed of their whereabouts. Although small in scale, this part of the research suggested positive support for such devices, with little concern about the ethical issues or stigma of ‘tagging’. However, there were practical suggestions about the design, including the need to be discreet, easy to operate and charge. (Study 25)

Looking at wearable technology, another project on remote monitoring brought together different disciplines to design a prototype for smart clothing for older people walking outdoors. The research team included experts in textiles, design, electronics and care of older people. The clothes included electronic tags and sensors of heart rates and activity levels. (Study 26)

The majority of people with mild to moderate dementia are looked after by family carers. One interactive system was directed to carers of people with dementia. This consisted of a smart television, with information and advice on everyday caring challenges, social networking platform with other carers and remote monitoring, with the carer uploading information which might trigger intervention by the health team. Initial findings from the small study suggested improvements in carer quality of life for those using the system, but no significant reduction in demands on carers. This was tested in a small pilot trial involving thirty carers in three pilot sites across Europe, including the UK. (Study 27)

Staying in touch

Social isolation and loneliness pose real risks to health. This is particularly true for older people. Technology can play a part in supporting social contact – seen in some of these integrated monitoring schemes which allow older people to stay in touch with family and friends. One large NIHR study is testing a web-based social networking tool. This is supported by trained facilitators who help people identified as being at risk of loneliness to map their existing social networks and identify interests and preferences. Facilitators then use online resources to match individuals to relevant activities and community groups in their area. The ambitious trial should deliver useful evidence for those planning services. (Study 28)

But these schemes can be difficult to deliver. Another NIHR study wanted to test a telephone befriending scheme for older people delivered by trained volunteers. This involved one to one telephone calls followed by group telephone sessions with peers. The pilot study never moved on to a full trial, as the voluntary organisations failed to recruit enough volunteers. (Study 29)

Technology can also be used to stimulate and encourage mental wellbeing, as well as make connections with others. One study in care homes had small groups of residents with a facilitator using technology to access photographs, videos and music by a touchscreen. Results from a before-after test suggested improvements in memory and quality of life which were sustained over some months. These promising results need further testing. (Study 30)

While technology will never replace the human touch of caring, enhancing care through new technologies can offer real benefits to older people and their families. We need the right research to know which technologies for which people will really help them stay well at home.

Alice Roe, Professionals & Practice Programme Officer – Age UK

A recent international review looked at various technologies to encourage social interaction in care homes. What evidence there was suggested that interventions to bring residents together and digital aids or companions like robotic pets appeared to have a positive effect on loneliness and social isolation. But there was no evidence to suggest these might be better than other non-technological solutions to make people feel more connected (Study 10).

There is more interest now in the role of technology in helping to reduce loneliness and social isolation as well as improve the health of older people. This is currently under-used. A recent survey (Study 8) found that almost no local authorities were using telecare to address loneliness in older people. Future systems and services are likely to give social wellbeing as much importance as health outcomes in assessing the impact of particular initiatives to support ageing well at home.

Designing better environments

Local authorities are required to make reasonable adjustments to homes to help older and disabled people to live independently. The role of the occupational therapist is critical, assessing the individual and the home to see what changes and assistive technology might help. There are different kinds of adaptations that can be made to help older or disabled people live at home. These include a range of equipment from simple aids to help with everyday living tasks to more complex adaptations, such as wet rooms and domestic lifts. There are also changes which can be made to streets and neighbourhoods to make them safer for older people or those with dementia and other conditions. A number of research projects in the last ten years have explored different ways in which homes and neighbourhoods can be made more age-friendly through good design.

This review will help occupational therapists understand recent research which has tested and developed technology to help older people live longer at home. It is important to realise that you don’t have to be a specialist in the field to incorporate everyday technology into practice. To support health and care needs, occupational therapists should ask technology related questions within the assessment process such as; “Have I asked my service user if they use technology at home? Would they be interested in using technology to help or support them?” in order to realise the full potential that digital technologies may offer and match the right technology to the needs of the person.

Dr Gillian Ward, Research and Development Manager, Royal College of Occupational Therapists

Bathroom

Problems with bathing and toileting present major challenges for many frail older people. It is also the place where many falls happen. One project reporting in 2011 worked with older people (and using older aged researchers to capture views and experiences of older people) to develop a prototype Future Bathroom. This involved a ‘living lab’ to study how older people get in and out of baths and showers, then developing and testing solutions. This included flexible equipment and adaptations, as needs and abilities change over time. (Study 31)

Bathing adaptations are one of the most common demands for equipment. There are often long waiting times to assess and meet these needs. To date, there has been no good evidence on the effect of bathing adaptations on function, health and wellbeing of older people and the impact of delays. One NIHR study is testing the feasibility of a trial to compare the effects after three and six months of people getting immediate adaptations with those waiting. (Study 32)

I was interested in reading about the research on changing kitchens and bathrooms with special devices. But it made me think – why not make all designs disabled user friendly, so no adaptations are needed!

Kate Brown, service user

Kitchen

Another critical space in the home is the kitchen. Making it easier for older people to cook and prepare food is important to maintaining independence. One study used observational and qualitative research with 48 older people to understand how they used space in their kitchen and what could be improved. Researchers identified problems with vision and lighting, including difficulties in reading controls on ovens or food packaging instructions. Surfaces and appliances were often at the wrong height and cupboards were difficult to access. People with arthritis and other conditions had limited strength and dexterity to open jars or lift heavy dishes. There were other challenges around the space and layout of typical kitchens, especially for those with limited mobility or using wheelchairs. Researchers looked at ways the traditional ‘cooking triangle’ (pattern of moving between sink, fridge and cooker) could be adapted for older people with limited function. As a result of this research, solutions for adaptations and for newbuild kitchens suitable for older people have been shared with users, designers and manufacturers. (Study 33)

Outside the home

Other research has looked outside the home to the neighbourhood and wider environment. One study looked at older people’s experience of mobility and challenges in the built environment. This focused on particular transition points, including when people stopped driving or lost sight or hearing. Research projects included tracking accessibility for mobility scooters and the implications for town planners, and use of a prototype app to customise walking routes for people with particular mobility challenges. (Study 34)

It is important to start with the needs and experiences of older people in their community. Qualitative research with older people experiencing confusion and memory loss identified some of the activities people found most enjoyable and which technologies might be helpful to adapt the environment to these needs. (Study 35).

Indeed, some projects are using researchers from fields like neurosciences to understand better how people with dementia navigate spaces inside and outside the home. This includes use of visual cues to help people reach the right door or room. (Study 36) This early research could lead to useful insights on technologies and design features for adapting homes and care homes for people with advancing dementia. (Study 37)

Another project looked at the building and technology design of care homes to maximise independence and social interaction for residents. The research involved architects as well as experts in design, ergonomics, ageing and engineering. Outputs included software to help architects involve residents in designing and planning homes and prototype systems, including monitoring technologies and sensors. (Study 38) In Sheffield, a similar mix of architects, urban planners, landscape designers and public health researchers worked with older people and housing and care staff to look at ways of adapting or designing housing and neighbourhoods to maximise mobility. Outputs varied from prototypes for new build houses to neighbourhood renewal schemes. (Study 39)

A similar tool was developed in 2010 to help architects to make building modifications or design new homes to meet the needs of older people. This is intended for extra care housing, sheltered housing and adaptations of regular houses. (Study 40)

Future directions

What do we know already?

This review has highlighted some recent UK-based research on aspects of assistive technology for older people. This is a field of rapid growth with developments worldwide. We have emphasised some of the learning on using and implementing devices and technology systems and their place in keeping older people safe and well at home.

The state of knowledge is emerging in this field. To date, one of the largest research investments has been in the large-scale trial starting around ten years ago of a telehealth and telecare scheme in three demonstrator sites across the UK. There were different strands of work in this complex programme of evaluation. Early results suggested some impact for those with chronic disease in reducing the number of deaths and hospital admissions (Steventon 2012) but, overall, the telecare initiative did not appear effective (Steventon 2013) or cost-effective. (Henderson 2014).

These kinds of large evaluations have been useful in managing expectations about expected efficiencies or immediate improvements. It is often said that technology is not a ‘silver bullet’ for addressing complex problems. It also highlights the need for a range of research approaches to understand how best to realise the gains of technology to improve everyday life for older people. Trials are largely designed to answer simple questions - ‘ does it work?’, ‘does x work better than y?’ In this field, a range of approaches is needed to understand not just the impact on particular outcomes, but also how technologies are used and the ways in which they might lead to improvements for individuals in particular contexts. Even simple technologies should be considered as complex interventions. Research to date underlines the limitations of a ‘plug and play’ mindset when implementing technology systems for older people.

What do we still need to know?

We have not carried out a systematic analysis of gaps in research. However, our expert group has identified some important areas of uncertainty. We need more high quality evaluations of impact and outcomes in using technology in the home. This report has shown much descriptive and developmental work to produce prototypes with lab-style testing. More work is needed to provide summative assessments of technology in use.

Much of the evidence to date has been informed by technology ‘push’, rather than the ‘pull’ of user need. Future research has to involve older people and carers in the design and testing of solutions and in prioritising the problems to be addressed. Future research should see solutions which are co-designed by those with lived experience of the challenges of ageing at home.

A priority for future development is collaborations between researchers, users and industry to see how everyday technology – from smartphones to virtual assistants, like Amazon Echo – can be adapted for the needs of older and disabled people. Given the common issue of an ageing population, there is an urgent need for large technology providers to address issues of disability and ageing.

The needs and abilities of carers will be different from the individuals they look after at home. Research to develop and test bespoke technology for carers is needed. This might include technologies to reduce isolation for carers, building on more general evidence such as an NIHR trial of support for dementia carers. (Livingston 2014)

In terms of future research, the World Health Organisation set an agenda in 2017 for future global research on assistive technology. There were two important guiding principles. One was that research should be user-driven. But secondly, a social or environmental approach, rather than a medical model, is appropriate to understand individual needs and use of technology. This means that researchers would need to consider the acceptability and appropriateness of technologies for the individual and their social contexts. It also has implications for the range of methods needed to develop and evaluate these technologies.

Research is also needed which addresses the ethical and moral issues around use of assistive technology. This is a dimension that should be considered in designing all studies in this area, as well as a research topic in its own right.

This review has highlighted a number of recent studies from an emerging and relatively new field of knowledge. We still do not know enough about the extent to which the right technologies can help older people to stay living longer safely and well at home. This review has underlined the importance of understanding the needs and experiences of older people and providing ongoing support from trained staff to make the most of technologies in their everyday lives.

This is an emerging and important field, which will be strengthened in coming years. NIHR has a role to play in this, not only through national programmes to deliver relevant research to health, social care and public health services but also through a dedicated stream to bring researchers and industry together to develop useful new technologies (i4i). NIHR is supporting a number of calls relating to new research on digital technologies to improve health and care. This is just one of many opportunities for new research in this area. In March 2018, the government announced £300 million as part of its Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund to address the challenges of healthy ageing in the UK. This is an area of rapid growth, where high quality interdisciplinary teams are needed to develop workable solutions to help us all to live at home as well as possible as we get older.

Questions arising from this evidence

Questions for commissioners of assistive technologies

- How can technology help us to support older people living with complex conditions at home? What benefits can we realistically expect?

- What assistive technology could we consider here, for instance remote monitoring and support for older people with heart failure?

- Have our technology solutions involved service users in their testing and design?

- How are these initiatives being monitored and evaluated?

- Have our staff had the right training to match technology to individual needs and to support their ongoing use in the home?

- What housing and neighbourhood designs do we need to create an ageing-friendly environment?

Questions for health and care professionals working with older people

- Have I received training to assess the needs and abilities of older people and the technologies that could help?

- How do I keep up to date with new technology?

- Have I asked my service users what technology they use at home and what for?

Questions for older people and carers

- What tasks and activities around the home do I find difficult?

- Which matter most to me?

- What devices or technologies might help?

- What support would I need to feel confident in using this every day?

- Who can I call if I need more help?

Disclaimer: This independent report by the NIHR Dissemination Centre presents a synthesis of NIHR and other research. The views and opinions expressed by the authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. Where verbatim quotes are included in this publication, the view and opinions expressed are those of the names individuals and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR of the Department of Health and Social Care.

Study Summaries and References

EFORTT: Ethical frameworks FOR Telecare Technologies

Published, 2013, Mort

This qualitative study used observations of telecare-in-use and citizens’ panels to develop an ethical framework for telecare systems. It took place in England, Spain, the Netherlands and Norway between 2008 and 2011. Researchers observed practitioners’ and managers’ meetings; local telecare call / monitoring centres; installation visits in older peoples’ homes; needs assessments; training events and conferences. Researchers conducted interviews with older people and technology companies, and held 22 citizens’ panels across the four countries, comprising older people and carers. Respondents felt strongly that telecare is not a substitute for human carers, it has care limitations and creates additional work, involving new workers and relying on social networks of friends, family and neighbours. Telecare requires users and carers to weigh up potential reductions in privacy with gains in freedom. Some telecare systems promote independence; others increase dependency. Older people may not use the telecare as intended, for example not wearing falls sensors to avoid triggering them, or ‘over-using’ telecare to increase social contact with staff. Users, carers and staff sometimes worked together to make devices more practically useful. The authors concluded that telecare has limitations, users and carers should be engaged in decision-making throughout, and systems adapted to meet individual needs.

Mort M, Roberts C, Pols J, Domenech M, Moser I. Ethical implications of home telecare for older people: a framework derived from a multisited participative study. Health Expectations 2015 Jun; 18(3): 438-449. First published 06 August 2013.

https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12109

Funder - European Union FP7 Science in Society Programme

Published, 2016, Robinson

This qualitative study involved semi-structured interviews with GPs (n=17), people with dementia (n=13) and family carers (n=26), in the North East of England between 2013 and 2014. All participants had practical experience of assistive technology, including fall alarms, notice boards, pill dispensers and easy to use telephones. GPs, people living with dementia, and carers, were all uncertain about how to find information on assistive technology. They all saw voluntary sector organisations as important, trusted resources. People with dementia and their family carers, rather than health and social care services, appeared to be the main drivers of increasing awareness and use of assistive technology in dementia care. GPs felt that assistive technology was not a core part of their role in dementia care. Responsibility for dementia care spreads across different services and professionals, highlighting an urgent need for more integrated working. Participants suggested a single point of access for information and support, such as a dementia adviser or nurse specialist. Future research could usefully be carried out over a more varied geographical area, and involve perspectives of the wider dementia care team, and of people with dementia and their carers who are not already engaged in local support networks.

Newton L, Dickinson C, Gibson G, Brittain K, Robinson, L. Exploring the views of GPs, people with dementia and their carers on assistive technology: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2016; 6:e011132. doi 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011132

https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/6/5/e011132

Funder - NIHR Professorship

Published, 2015, Greenhalgh

This qualitative study in London and Manchester involved three stages: (i) interviews with seven technology suppliers and 14 service providers; (ii) ethnographic case studies of 40 people aged between 60 and 98 with multi-morbidity and assisted living needs; (iii) 10 co-design workshops with users, carers, suppliers and providers of assistive technology. The researchers identified six themes of “quality” telehealth or telecare: Anchored in a shared understanding of what matters to users; Realistic about illness and progression; Co-creative; Human, supported through personal relationships and social networks; Integrated, with effective information sharing; and Evaluated (the ‘ARCHIE’ principles). They concluded that although technological advances are important, they should be based on a user-centred approach to design and delivery. Telehealth relies on the ability of the person to use the equipment and / or help from family and friends. The focus should move from assistive technology products in general, to how products perform practically to meet individual needs over time, and how different components can combine for flexible use across devices and platforms. The authors also recommend a shift away from standardised care packages towards a more personalised commissioning model.

Greenhalgh T, Procter R, Wherton J, Sugarhood P, Hinder S, Rouncefield M. What is quality in assisted living technology? The ARCHIE framework for effective telehealth and telecare services. BMC Medicine 2015;13(91). https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-015-0279-6

Funder – TSB Assisted Living Platform and NIHR Senior Investigator Award

Published, 2016, Mountain

This small qualitative study comprised semi-structured interviews with 22 people who did not currently use telecare, but for whom it could be relevant. Fourteen participants were aged 65 or over. The researchers noted a weakness in that participants were self-selected, and only one had previously refused telecare. They defined telecare as technology that remotely monitors changes in an individual, and is distinct from telehealth, which involves a health-care professional providing remote care using a digital network. This study focused mainly on alarms triggered by the user (e.g. pendants), and sensors (e.g. temperature sensors) which detect conditions and trigger alerts automatically, rather than on recently emerging technology which can monitor lifestyle, such as Global Positioning System tracking. Barriers to telecare use included financial cost to the individual, stigma, and perceived reduction in independence. Decision-making was also affected by the design and suitability of telecare, the impact of changing health, opinions within an individual’s support network including ‘peace of mind’, and information about available telecare. Individuals often perceived telecare as a last resort. The researchers recommended raising awareness of telecare, and suggested that adapting technology that is already widely accepted, such as mobile phones, might be more popular than carrying separate devices.

Bentley CL, Powell LA, Orrell A, Mountain GA. Making Telecare desirable rather than a last resort. Ageing & Society 2018; 38(5)926-953. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Published online December 21, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X16001355

Funder - NIHR CLAHRC Yorkshire and Humber

Advancing Knowledge of Telecare for Independence and Vitality in later life project (AKTIVE)

Published, 2014, Yeandle

This mixed methods study looked at the everyday experiences of 60 frail older people using telecare in Leeds and Oxfordshire, and prone to falls or living with memory loss or dementia. It comprised repeat visits over six to nine months, interviews with relatives, care workers and neighbours, and workshops with response centre staff and manufacturers. Telecare in participants’ homes included pendant alarms, door sensors, gas leak detectors, medication reminders and tracker devices. Results indicated that design, comfort, ease of use and understanding how the technology worked were important. Various practical issues caused concern, such as setting off false alarms, lack of direct communication between the monitoring centre and the user, and lack of routine maintenance. Frailty had a serious impact on the 60 participants’ daily lives, and many felt lonely. When the right equipment was provided, telecare was successful not only in providing safeguards, but in helping people get out and about, increasing their vitality and reducing family tensions. If telecare was not appropriate to their needs, people rejected it. The researchers concluded that telecare is not an intervention but a ‘tool for living’. It is best to introduce technology early, before a crisis. Individual circumstances, which can change rapidly, should determine the timing of upgrades. At its best, telecare can enhance networks of support.

http://www.aktive.org.uk/conference2014-presentations.html

Funder – TSB

Published, 2016, Mair

The Delivering Assisted Living Lifestyles at Scale (dallas) programme is a large-scale, UK-wide technology programme that aims to deliver a broad range of digital services and products to the public to promote health and well-being. Four multi-agency partnerships, involving public, voluntary and private organisations, aim to deliver services to 169,000 individuals across remote, rural and urban areas. Technologies include interactive, person-centred websites, telecare, electronic personal health records and mobile applications. This implementation study used qualitative methods, over time, to identify challenges. Data collected included interviews with stakeholders involved in service design and delivery at the start (n=17) and midway through implementation (twelve to fourteen months later, n = 21), barrier and solutions reports, observational logs, and evaluation interviews with project leads (n=5). The study identified five key implementation challenges: establishing large, multi-agency partnerships; needing resilience to cope with set-backs and external changes; a tension between involving users in design, and also delivering quickly and widely across the UK; branding and selling digital health services to the public; sharing data between organisations and ensuring different technologies can work together, which may seem threatening to commercial partners. The authors concluded that the dallas programme is building up an extensive network of expertise.

Devlin AM, McGee-Lennon M, O’Donnell CA, Bouamrane M, Agbakoba R, O’Connor S et al. Delivering digital health and well-being at scale: lessons learned during the implementation of the dallas program in the United Kingdom. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2016 Jan; 23(1): 48–59.

https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocv097

Funder - NIHR, Innovate UK, the Scottish Government, Scottish Enterprise, Highlands and Islands Enterprise

Ready, Steady, Go: A telehealth implementation toolkit

Published, 2012, Brownsell and Ellis

This toolkit provides a detailed framework for the implementation of telehealth at local level. It is based on a systematic review of studies evaluating telehealth implementation, and the authors’ own experience of telehealth implementation and change management. Many projects worked well at a small scale, but struggled when deployed more widely. Local context made a significant difference. The toolkit has five phases: understanding the vision, preparation and securing support, testing and training, focus, and endurance. After implementation, review and reflection is required to decide whether to close down the service, keep it as it is, or expand it. A later qualitative study considered the key qualities of a successful telehealth implementation toolkit, and assessed the usability of the ‘Ready, Steady, Go’ toolkit. The study experienced recruitment challenges. It comprised interviews (n=13) and a focus group (n=10) with telehealth experts from academia, the NHS, industry and a UK and European local authority. The results highlighted the importance of considering staff workload and time needed to use the toolkit, layout, inclusion of case studies, having a practical focus and services being fully ready before implementation. These results will inform the development of a web-based version of the Ready, Steady, Go toolkit.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B3-SF4FxenwJdmhGNnBHV1ZZNGc/view

Powell LA, Ellis T and Mawson S. What makes a successful telehealth implementation toolkit: A qualitative study exploring the usability and perceived value of the “Ready, Steady Go” Telehealth Toolkit. Academic Report 2015. NHS Sheffield Clinical Commissioning Group, the University of Sheffield and NIHR CLAHRC Yorkshire and Humber; 2015.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B3-SF4FxenwJaWxjR0R4Z2tGX1E/view

Funder - NIHR CLAHRC South Yorkshire and EC

Published, 2018, Woolham

This study aimed to understand how and why local authority Adult Social Care departments in England are using telecare to support older people. It comprised semi-structured interviews with telecare managers and stakeholders (still to be published), and an online survey of telecare managers in all local authorities in England (n=152) between November 2016 and January 2017. The survey achieved an overall response rate of 75% (n=114). It found that only 24% of respondents had developed their telecare strategy in collaboration with local NHS and other partners. Many adult social care departments said telecare saved money but found it difficult to evidence this claim. Assessments for telecare were not always done, and not always done in people’s homes. Most training was brief and provided by manufacturers or suppliers. Small numbers of telecare suppliers were used. The most commonly provided telecare items were wearable pendant alarms and fall detectors. A 24/7 response service was not always used and sometimes, if unpaid carers were not available around-the-clock, telecare was not provided. The researchers called for better matching of need to telecare through greater investment in training, deploying a wider range of devices, and widening strategic focus beyond risk management, for example using telecare to improve social contact.

Woolham JG, Steils N, Fisk, M, Porteus J, Forsyth K. The UTOPIA project. Using Telecare for Older People In Adult social care: The findings of a 2016-17 national survey of local authority telecare provision for older people in England. London: Social Care Workforce Research Unit, King's College London; 2018.

https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/files/87498580/Utopia_project_report.pdf

https://www.sscr.nihr.ac.uk/projects/P89.php

Funder – NIHR SSCR

Study 9 published

Overcoming the Barriers to Mainstreaming Assistive Living Technologies (MALT)

Published, 2015, Taylor

These qualitative studies explored why the UK has not embraced telehealth as quickly as anticipated. Previous studies suggested acceptance by frontline staff was a key barrier. The researchers conducted case studies of four community health services in England that use telehealth to monitor patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Chronic Heart Failure. They interviewed nursing and other frontline staff (n=84), and managers and key stakeholders (n=21) between May 2012 and June 2013. Attitudes towards telehealth ranged from resistance to enthusiasm. Early negative experiences had a long-lasting impact. Early successes helped overcome barriers, as did reliable and flexible technology; dedicated resources; ongoing training with time to experiment; ‘local champions’; targeting the right patients; and a partnership approach. The authors concluded that telehealth will not become embedded within mainstream health services until clinicians see demonstrable patient and clinical benefits. They also conducted ‘action research’ with 57 staff and one patient, in which they supported each service to increase telehealth adoption, from July 2013 to April 2014. Services were able to make planned changes to telehealth, and to share learning across stakeholders. However, continual changes to service provision hampered adoption, implementation and staff motivation, as did technological barriers and uncertainties about goals.

Taylor J, Coates E, Brewster L, Mountain G, Wessels B & Hawley MS. Examining the use of telehealth in community nursing: identifying the factors affecting frontline staff acceptance and telehealth adoption. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2015 Feb; 71(2): 326-337.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jan.12480

Taylor J, Coates E, Wessels B, Mountain G & Hawley MS. Implementing solutions to improve and expand telehealth adoption: participatory action research in four community healthcare settings. BMC Health Services Research 2015; 15(1): 529.

https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-015-1195-3

Funder - Assisted Living Innovation Platform, with support from the TSB and the ESRC

Innovation to enhance health in care homes: Rapid evidence synthesis

First Look Summary published, 2018, Hanratty

This study reviewed published research about enhancing health in care homes. It focused on four key areas: use of technology, workforce, community and engagement, and evaluation. 65 studies from high-income countries, published between 2000 and 2016, were included across the four categories. The authors concluded that there is a lack of large, high quality research studies, particularly from the UK. Digital technology has many potential uses in care homes, and experimental studies have investigated a range of technological interventions. However, a majority of studies are pilot or feasibility trials, and not large enough to detect clinically significant outcomes. Studies frequently identify cost, ease of use and staff demands as both barriers and facilitators in the use of technology. The evidence base about impact on residents’ well-being does not allow firm conclusions to be drawn. Resident and family participation is essential in future research.

https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/157705#/

Funder – NIHR HS&DR 15/77/05

Study 11 published

Consumer Models for Assisted Living (COMODAL)

Published, 2016, Ward

This mixed methods project aimed to understand the barriers to market development of electronic living technologies. People aged 50-70, approaching retirement and older age, helped to create business models led by consumers, rather than based solely on needs, to reduce potential stigma. Consumers, industry and non-governmental organisations and charities worked together. There were five work programmes: understanding consumer needs; developing solutions and consumer led business models; developing an industry support system for practical implementation; developing a guide for industry based on consumer insights; spreading the messages. The research included focus groups and street surveys with people aged 50-70, joint work with consumers and industry, and interviews, workshops and a telephone survey with industry representatives. The top three barriers for consumers were cost, knowing how to choose a product, and lack of awareness of helpful products. The top three enablers were believing a product would make a difference, be affordable and make life safer at home. Consumers would like to test products out in practice, and would like products and services to link together to meet their independent living needs as a whole. The project developed four business models – ‘complementor’, ‘diversifier’, ‘independent advisor/broker’, and ‘insurance’ – which it has presented to industry.

COMODAL COnsumer MODels for Assisted Living: Project Summary and Findings http://www.comodal.co.uk/

Ward G, Fielden S, Muir H, Holliday N, Urwin G. Developing the assistive technology consumer market for people aged 50-70. Ageing and Society 2017 May; 37(5):1050-1067. Published online February 22, 2016.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X16000106

Funder - Innovate UK

Structured telephone support or non-invasive telemonitoring for patients with heart failure

Published, 2015, Inglis

This Cochrane review examined evidence from 41 randomised controlled trials that compared heart failure management delivered through structured telephone support and non‐invasive telemonitoring with usual post-discharge care, to people living in the community. Participants were aged 18 years and over. Two of the studies involved the UK, and over half were conducted in the USA. 25 of the studies evaluated structured telephone support (total of 9332 participants), and 18 evaluated telemonitoring (total of 3860 participants). Two studies evaluated both interventions. The authors concluded that, compared to usual care, implementation of structured telephone support and non‐invasive home telemonitoring can reduce mortality and heart failure‐related hospitalisations, and improve quality of life, heart failure knowledge and self‐care behaviours. For the eighteen studies focused just on telemonitoring, there was a 20% reduction in mortality and a 29% reduction in heart-failure related hospitalisation. There was not an important effect on all-cause hospitalisations. The quality of evidence ranged from very low (all-cause hospitalisation) to moderate (all-cause mortality and heart failure-related hospitalisation). Most participants, including the elderly, learned to use the technology easily and were satisfied with the interventions. The authors noted that, in most cases, the equipment was provided as part of the study, and therefore there may be implications for purchase, installation and maintenance of equipment during everyday practice.

Inglis SC, Clark RA, Dierckx R, Prieto‐Merino D, Cleland JGF. Structured telephone support or non‐invasive telemonitoring for patients with heart failure. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 10. Art. No.: CD007228. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007228.pub3.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD007228.pub3/full

Funder - Cochrane: Cochrane Heart Group

Protocol published, 2013, Howard

ATTILA is a pragmatic, randomised controlled trial involving 500 participants. It compares outcomes amongst people with dementia who receive assistive technology and telecare, and those who receive equivalent community services without technology. The trial will test whether fewer people in the technology group enter institutional care over a five-year period. It will consider care costs for participants, quality of life, and caregivers’ levels of stress. All participants will receive a needs assessment from their local authority. The technology group will then receive an individually tailored, dementia-specific, technology package, decided on by the local authority. This technology may include monitored sensors (e.g. property exit sensors, bed exit sensors) and stand-alone systems (e.g. automatic lights, carer alerting devices). The control group will receive equivalent community services without technology, apart from non-electronic items such as walking frames, smoke and carbon monoxide detectors, and simple pendant alarms and key safes, if required. The trial plans to report results in Spring 2019.

https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/105002/#/

Funder – NIHR HTA - 10/50/02

Study 14 published

Seamless User-centred Proactive Provision Of Risk-stratified Treatment for Heart Failure (SUPPORT-HF)

Published, 2015, Rahimi

This study developed a home tele-monitoring system for patients with heart failure. Fifteen patients took part in an initial co-design workshop, and 52 participants with heart failure (average age 77 years) then tested the system over six months. The researchers used patient observations, interviews and analysis of the remote data, to improve the system’s ease of use. The system operated via a tablet PC application that wirelessly collected information on weight, blood pressure and heart rate. It enabled participants and the study team to exchange messages, and had built-in alerts. Almost half of the participants had very little or no previous experience with digital technologies. It took participants 1.5 minutes to complete the daily monitoring tasks. 46 participants completed the final survey, of which 93% said they found the system easy to use, and 38% asked to keep the system after the study ended. The system did not involve active intervention by clinicians, but patients felt connected and reassured. A follow-up randomised trial (SUPPORT-HF2), explored whether integrating the home monitoring system with electronic health records and personalised feedback improved its effectiveness. It recruited 202 patients with heart failure from seven UK hospitals. The primary outcome was the use of recommended medical therapy. The trial has completed and data analysis is underway.

Rahimi K, Velardo C, Triantafyllidis A, Conrad N, Shah SA, Chantler T, et al. A user-centred home monitoring and self-management system for patients with heart failure: a multicentre cohort study. European Heart Journal - Quality of Care and Clinical Outcomes 2015 November; 1(2):66–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjqcco/qcv013

https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/13114102/#/

Rahimi K. Home monitoring with IT-supported specialist management versus home monitoring alone in patients with heart failure: Design and baseline results of the SUPPORT-HF 2 randomized trial. American Heart Journal. Available online 25 September 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2018.09.007

Funder – NIHR HS&DR - 13/114/102, NIHR Oxford BRC Programme and NIHR Career Development Fellowship

Study 15 published

NANA - Novel Assessment of Nutrition and Ageing

Published, 2018, Astell

The Novel Assessment of Nutrition and Ageing toolkit collects information over time about older people’s health and behaviour via a touchscreen computer, on which people enter information about themselves. Two studies explored six items for measuring self-reported mood and appetite as part of this toolkit. One was conducted in a supervised laboratory setting with community-living older adults (n=48), and compared the computerised items with established paper measures, in three individual testing sessions over a week-long period. The researchers concluded that the computerised items were a valid and reliable way of measuring participants’ mood and appetite, and there was significant correlation between the computerised items and established methods. The second study was conducted in people’s own homes (n=40), unsupervised, over three periods of seven days each. Participants were also assessed at home and in clinic before and after the measurement periods. The computerised methods worked well at home. Limitations included most participants being relatively high-functioning, with previous experience of using computers. Adaptations would be needed for people with visual impairment. The researchers concluded the toolkit can be effective in identifying people who are experiencing changes in mood or appetite, and in understanding more about the links between mood, appetite and health.

Brown LJE, Adlam T, Hwang F, Khadra H, Maclean LM, Rudd B et al. Computerized self-administered measures of mood and appetite for older adults: the Novel Assessment of Nutrition and Ageing toolkit. Journal of Applied Gerontology 2018 Feb 1; 37(2): 157-176. First published online February 10, 2016. DOI: 10.1177/0733464816630636.

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0733464816630636#

Timon CM, Astell AJ, Hwang F, Adlam TD, Smith T, Maclean L et al. The validation of a computer-based food record for older adults: the Novel Assessment of Nutrition and Ageing (NANA) method. British Journal of Nutrition 2015 Feb 28; 113(4):654-64. doi: 10.1017/S0007114514003808

https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S0007114514003808/type/journal_article

Funder – NDAP

USEFIL: Unobtrusive Smart Environments For Independent Living

Published, 2015, Clarkson

This project aimed to develop low-cost applications to monitor activity, physical health and emotion, for older people living at home. It added software to off-the-shelf devices such as smart watches, tablets and smart TVs. A ‘smart mirror’ monitored users’ emotions and health indicators, such as pupil size. Users, family and friends, carers and health professionals logged in to an online project portal to see monitoring data and communicate with each other. A ‘decision support system’ analysed users’ data and flagged up problem trends in health. The system was tested at three sites in the UK, Greece and Israel, in the laboratory, and in the homes of thirteen older people aged over 65 who had had a stroke, were living with mild cognitive impairment or had chronic conditions (without dementia). Users completed questionnaires and took part in interviews, but full results are not available. Challenges included maintaining the system in users’ own homes. Early findings suggested differences in perception between the laboratory and the home. Overall, users found monitoring much more invasive at home, and harder to use without a facilitator there. Although smart watches felt less like monitoring devices at home, their use declined since they required daily charging.

https://usefil.eu/pudeliverables/USEFIL_WP8_D8%204_End_of_Project_Volume_v3.0.pdf

Funder - EC

The Mainstreaming on Ambient Intelligence (MonAMI) project

Published, 2012, Damant

This project aimed to develop computer technology to deliver care services for older and disabled people using mainstream devices, such as mobile phones and personal computers. Services included local and remote home monitoring and appliance control, safety and security alarms (such as visitor validation), and planning and reminder applications. Users first tested the technology in laboratories in six European countries: the UK, France, Germany, Slovakia, Spain and Sweden. A trial then took place in three communities in Slovakia, Sweden and Spain. 62 users (average age 79 years, 73% women, 90% living alone) tested the services in their own homes over a three-month period. Researchers conducted semi-structured interviews at the start and end of the trial-period. Results demonstrated that users with more disabilities, compared to those with fewer disabilities, found the services had a positive effect on their perceptions of security, and ability to manage pain. Overall, more than half of users rated the acceptability and usefulness of the services highly. However, users who were more independent and had better self-rated health benefited from the services more than users who were less independent and were in poorer health. The researchers concluded that this developmental model showed potential to improve the quality of life of older people with care needs.

Damant J, Knapp M, Watters S, Freddolino P, Ellis M, King D. The impact of ICT services on perceptions of the quality of life of older people. Journal of Assistive Technologies 2013; 7(1): 5-21. https://doi.org/10.1108/17549451311313183

Funder – EC

Published, 2011, Darlington

This project developed and tested a system for monitoring the elderly living at home, informed by an earlier study. It used motion sensors, and shared data between all those involved in the elderly person’s care, such as carers, the health professionals, social workers and friends. Researchers tested it in practice with 16 residents and their carers, as well as four medical professionals, in a sheltered housing complex in London. Five sensors were installed in each dwelling, in the kitchen, bathroom, living area, hall and bedroom. Carers could monitor over the web when, and how often, residents moved between different rooms. The researchers reported that all those involved, including residents, found the system easy to use and supportive. On several occasions during the trial, monitoring data revealed a problem, such as spending an unusually long time in the bathroom, which led to helpful intervention. Six participants chose to continue using the system after the trial ended.

https://gtr.ukri.org/projects?ref=TS%2FH000135%2F1

Funder - EPSRC

SOPRANO: Service Oriented Programmable Smart Environments for Older Europeans

Published, 2010