This is a plain English summary of an original research article. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and reviewer(s) at the time of publication.

In the UK, cervical screening is offered by GPs and other community services, but in the future, people could take their own samples at home. Research has shown that self-sampling for cervical screening had a lower carbon footprint.

Researchers suggest that cervical screening programmes could offer people the choice to take their own sample, which would reduce carbon emissions and could improve uptake.

More information on cervical screening can be found on the NHS website.

The issue: how to reduce carbon emissions from cervical screening?

In the UK, more than 3,000 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer each year. Cervical cancer is caused by persistent infection with human papillomavirus (HPV). At a screening appointment, a healthcare practitioner puts a tube-shaped tool (speculum) into the vagina to see the cervix, and uses a soft brush to collect cells from the cervix. The sample is sent to be tested for HPV.

An alternative screening method is for women to take their own swab at home (vaginal self-sampling). This method is currently offered in 17 countries, but not in the UK. Another potential method is for women to take a urine sample at home; this is currently being evaluated in the UK. Research suggests that taking a urine sample is widely acceptable and might encourage groups of women who are less likely to attend, particularly in minoritised groups, to take part in routine cervical screening.

The environmental impact of clinic-based screening relates to patient travel and use of the clinic’s resources, such as gas and electricity. By 2045, the NHS aims to release no more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than it offsets (net zero). Self-sampling could help achieve this aim.

This study compared the carbon emissions from different cervical screening methods.

What’s new?

The researchers compared carbon emissions associated with 3 cervical screening methods: samples collected by a healthcare professional versus vaginal and urine self-samples. They included all steps in each approach (from invitation to lab sample preparation). They collected data themselves and used other information sources (manufacturer materials, for instance).

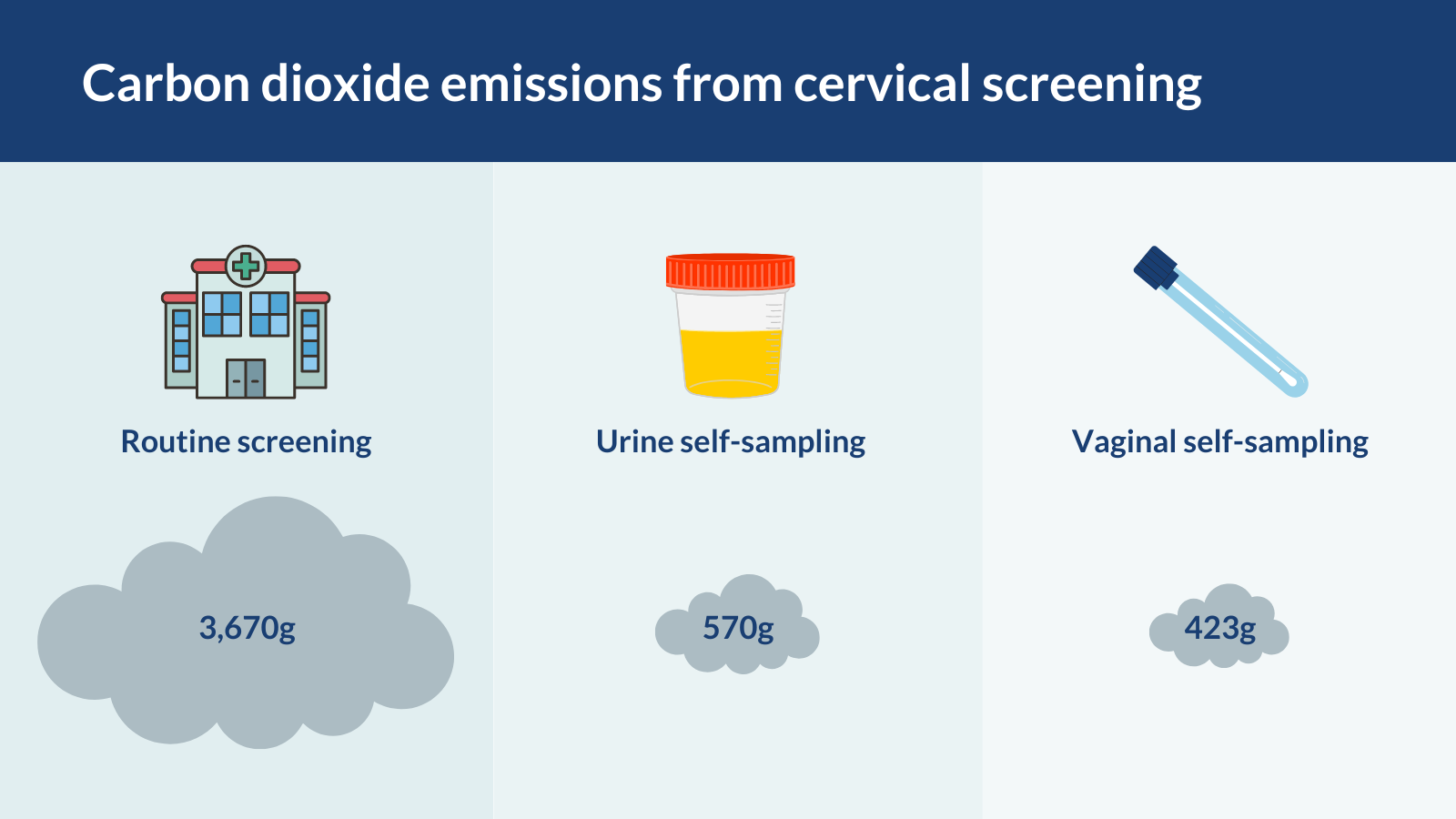

They found that routine screening at a healthcare service produces:

- 8.7 times more carbon dioxide (3670g) than vaginal self-sampling (423g)

- 6.4 times more carbon dioxide than urine self-sampling (570g).

In routine cervical sampling, most of the emissions came from running the appointment at a healthcare facility (2758g). Differences between self-sampling methods were minimal.

Why is this important?

NHS carbon emissions account for 4% of the UK’s carbon footprint; self-sampling could help reduce this. Self-sampling on a national scale could reduce carbon emissions by 4,076 tonnes, the researchers project. They hope their study inspires more research on how healthcare systems measure the environmental impact of diagnostic pathways and treatments.

Only 2 in 3 people (69%) take up the offer of cervical screening, and numbers are decreasing. Barriers include difficulty accessing appointments and the embarrassment, discomfort and sometimes painful nature of the speculum examination. As well as its positive environmental impact, self-sampling could avoid these issues and encourage more people to be screened. Research suggests that at least half of women would choose self-sampling if it were offered.

The researchers caution that if an in-person appointment for screening is not needed, the clinician is likely to see another patient instead. So emissions from patient travel, heating premises and so on, will continue. Over time, as more appointments become virtual or are changed to reduce their carbon footprint, overall emissions could be reduced.

The researchers made several assumptions about how self-sampling would work in practice and could not account for some outcomes (such as posting sample kits that were not returned).

What’s next?

If self-sampling is offered in the UK, people will need information about the benefits and downsides to each approach, including the environmental impact, to make an informed decision about how to be screened.

This study was part of a wider project exploring urine self-sampling for cervical screening, including test accuracy, acceptability and cost-effectiveness. Further research is needed to evaluate real-world implementation of self-sampling for cervical screening.

You may be interested to read

This is a summary of: Whittaker M, and others. A comparison of the carbon footprint of alternative sampling approaches for cervical screening in the UK: A descriptive study. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2024; 131: 699–708.

A report on reducing carbon emissions in healthcare by the Health Foundation.

A study on urine testing for cervical screening: Davies JC, and others. Urine high-risk human papillomavirus testing as an alternative to routine cervical screening: A comparative diagnostic accuracy study of two urine collection devices using a randomised study design trial. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2024. DOI: 10.1111/1471-0528.17831.

Cost-effectiveness study of self-sampling and clinician-sampling for cervical screening: Huntington S, and others. Two self-sampling strategies for HPV primary cervical cancer screening compared with clinician-collected sampling: an economic evaluation. BMJ Open 2023; 13: 1–13.

Funding: This study was supported by an NIHR Advanced Fellowship and the NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre.

Conflicts of Interest: One author runs a sustainability consultancy.

Disclaimer: Summaries on NIHR Evidence are not a substitute for professional medical advice. They provide information about research which is funded or supported by the NIHR. Please note that the views expressed are those of the author(s) and reviewer(s) at the time of publication. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

NIHR Evidence is covered by the creative commons, CC-BY licence. Written content and infographics may be freely reproduced provided that suitable acknowledgement is made. Note, this licence excludes comments and images made by third parties, audiovisual content, and linked content on other websites.