This is a plain English summary of an original research article. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and reviewer(s) at the time of publication.

Enhanced labels for alcoholic drinks include pictures to demonstrate their strength, plus an explicit statement of drinking guidelines. New research found that these labels could improve public awareness and understanding of the Government’s Low Risk Drinking Guidelines.

Government guidelines recommend a weekly maximum of 14 units of alcohol. However, public awareness of the guidelines is low, and they are not widely followed. Estimating numbers of units is challenging.

The researchers recommend the enhanced drinks labels, which they say would give the public clearer information to make informed choices. Levels of alcohol-related diseases are rising in the population and reductions in drinking are needed.

What’s the issue?

Alcohol consumption is a major public health issue. It is associated with more than 200 conditions, including heart disease, liver disease, and cancer. Greater consumption leads to more severe illness.

The UK government has published Low Risk Drinking Guidelines, which recommend a weekly maximum of 14 units of alcohol. But these guidelines are not well known and the harms of drinking are not well understood. Less than one in four (8-25%) of the population know what the guidelines say. More than 10 million adults drink more than the recommended weekly limit.

The guidelines describe ‘units’ of alcohol. A unit is approximately two teaspoons of pure alcohol. But alcoholic drinks vary widely in their strengths and serving sizes, and people find it difficult to estimate how many units they have drunk.

A new design of drinks labels, with pictures of units and a statement of the guidelines, may help. It could increase awareness of the guidelines and improve understanding of recommended limits.

What’s new?

Researchers carried out an online survey to compare six enhanced label designs against the industry standard. This current label does not state the guidelines.

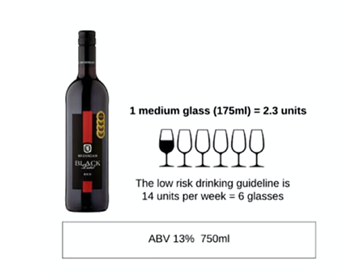

The enhanced labels all included the size and number of units in a serving (such as a glass of wine) or container (the bottle). They also related the units to the weekly limit. So, one label - shown below - stated that a medium glass of wine (175ml) is 2.3 units or one-sixth of the weekly upper limit. Beneath a diagram of six glasses (one filled, five empty) is the phrase, “The low-risk drinking guideline is 14 units per week = 6 glasses”.

Example of an enhanced label.

More than 7,000 volunteers each saw one type of label on various drinks (beer, wine, spirits). 500 participants also saw a health warning.

The researchers looked at how the type of label affected (1) knowledge of the guidelines, (2) understanding of how many servings and containers would take them to the upper limit, and (3) the perceived risk of drinking and their motivation to drink.

The researchers found:

-

- All enhanced label designs improved knowledge of the guidelines compared to the standard label. The best-performing designs showed a picture of containers, servings, or a pie-chart with the guidelines in a separate statement underneath. Knowledge of guidelines was more than doubled (increased from 22% to around 50%) with these best-performing labels.

- Participants underestimated how many servings (glasses) they could drink; the enhanced labels increased their accuracy.

- They overestimated how many containers (bottles) they could drink. Enhanced labels decreased accuracy and people seeing enhanced labels overestimated even more than others.

- Participants judged the alcohol content of beers more accurately than wine or spirits. This could be because people often drink from the bottle, so the serving and container size are the same.

- Enhanced labels did not affect the participants’ perceived risk of drinking, but slightly decreased their reported motivation to drink.

- A smaller group of 500 people also saw ‘Warning: Alcohol causes cancer’ under each design. It had no effect on their perceived risk of drinking, or their motivation to drink.

Why is this important?

The enhanced labels improved knowledge and understanding of the UK Low Risk Drinking Guidelines. Current drinks labels do not include the recommended limit of 14 units. The researchers would like to see labels changed along the lines of the best-performing labels: an explicit guideline statement, ideally under a picture.

The enhanced labels did not change people’s perceptions of risks, and slightly decreased participants’ stated motivation to drink. The findings suggest that enhanced labelling alone is unlikely to change behaviour on a large scale. However, enhanced labels can inform choices. The public has the right to accurate information and clear advice about the health risks of alcohol.

What’s next?

It remains to be seen whether the results of this survey will hold true in real-world situations. In busy supermarkets, for example, people are under time pressure and have other distractions.

This study suggests that labels relating to servings (glasses), rather than bottles, may work best. However, people at home tend to pour bigger drinks than standard servings in pubs and restaurants. Interventions to improve their understanding of a ‘unit’ may help them accurately track how many servings they are drinking.

Participants lacked understanding of the alcohol ‘unit’ on which the guidelines are based. They tended to underestimate the suggested maximum limit. It is possible that improved understanding of the guidelines could lead to an unintended increase in alcohol consumption. The researchers say it is important to stress that the risk of health conditions increases with the total amount drunk. The guidelines are not a threshold for ‘safe’ drinking and nor are they a weekly ‘target’.

You may be interested to read

The full paper: Gold N, and others. Effect of alcohol label designs with different pictorial representations of alcohol content and health warnings on knowledge and understanding of low‐risk drinking guidelines: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction 2020;116:6

The story by the IAS is based on findings from the Alcohol Health Alliance (AHA) UK report: Drinking in the Dark: How alcohol labelling fails consumers.

Funding: This study was supported by the NIHR School of Public Health Research, the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) Northwest London, and Public Health England (PHE).

Conflicts of Interest: The study authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer: Summaries on NIHR Evidence are not a substitute for professional medical advice. They provide information about research which is funded or supported by the NIHR. Please note that the views expressed are those of the author(s) and reviewer(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

NIHR Evidence is covered by the creative commons, CC-BY licence. Written content and infographics may be freely reproduced provided that suitable acknowledgement is made. Note, this licence excludes comments and images made by third parties, audiovisual content, and linked content on other websites.