This is a plain English summary of an original research article. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and reviewer(s) at the time of publication.

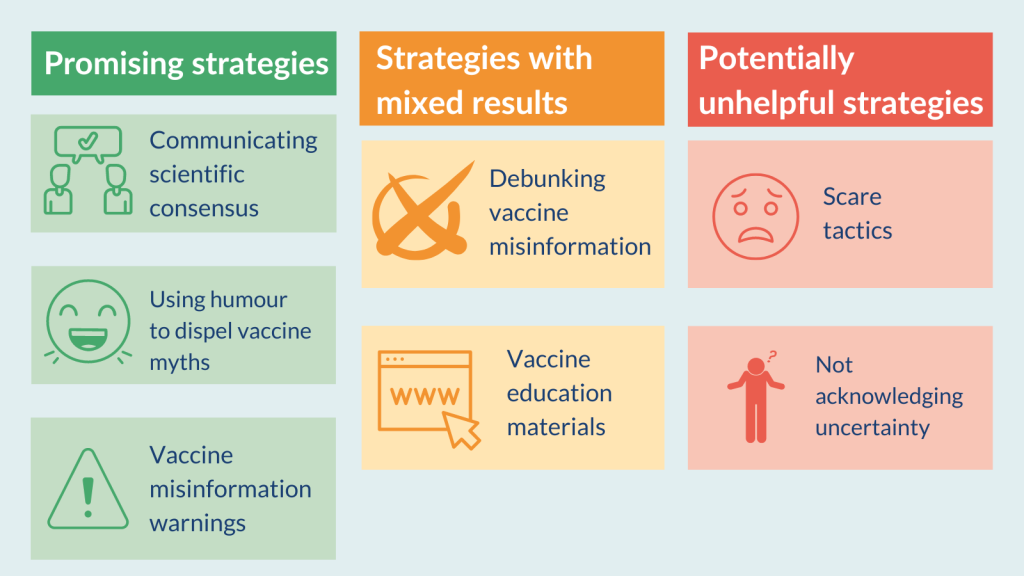

Communicating the scientific consensus that vaccines are safe and effective, and using humour to dispel vaccine myths, may tackle misinformation effectively. Scare tactics, and failing to acknowledge uncertainty, could be unhelpful. These and other findings come from a review of 34 studies into communication strategies to tackle untruths about vaccines.

Promising strategies

- Communicating scientific consensus

- Using humour to dispel vaccine myths

- Vaccine misinformation warnings

Strategies with mixed results

- Debunking vaccine misinformation

- Vaccine education materials

Potentially unhelpful strategies

- Scare tactics

- Not acknowledging uncertainty

The analysis informs public health communicators and policy makers about promising strategies to tackle vaccine misinformation. It also warns about strategies that could backfire, or have mixed results. Communicators will be able choose and tailor strategies for different audiences.

Further research is needed on how effective these strategies are in the real world and whether they increase vaccine uptake.

Information about vaccines is available on the NHS website.

What’s the issue?

Misinformation (inaccurate information unintentionally presented as fact) and disinformation (deliberate spread of false information) have been linked to lower levels of vaccine uptake. Both were widespread during the pandemic. But even before COVID-19, the World Health Organization (WHO) had identified vaccine hesitancy as a top global health threat.

Effective strategies to counter vaccine misinformation are crucial in encouraging vaccine uptake for COVID-19 but also for other diseases.

Researchers reviewed evidence on communication strategies used to tackle vaccine misinformation and to promote changes in people’s behaviours and attitudes to vaccination.

What’s new?

The review included 34 studies, including 25 randomised controlled trials. Most (21) were conducted in the US. The studies examined the effect of different communication strategies on people’s intention to get vaccinated, their vaccine-related beliefs, knowledge, and attitudes. They did not measure the impact on vaccine uptake.

The most promising strategies

- Scientific consensus - how many scientists or doctors agree that vaccines are safe. Presenting the weight of evidence reduced people’s belief in incorrect information in 2 studies.

- Humour - tweets using humour to dispel vaccine myths, for example. Humour increased confidence in vaccines and tackled misinformation in 3 studies.

- Vaccine misinformation warnings – a line at the top of vaccine-related Google searches, for example. In 2 studies, these warnings decreased belief in misinformation and improved vaccine knowledge and attitudes. Another study looked at the effect of the warning combined with vaccine education materials, so the effects of the warning alone were less clear.

Strategies with mixed results

- Debunking misinformation – websites and pamphlets that present common vaccine myths with corrective facts, for example. In 4 studies, these interventions were effective and reduced people’s belief in incorrect information. But in 2 studies, they increased these beliefs, and in another 2, had no clear effect.

- Education materials – vaccine facts on government websites, for example. Education seemed to improve vaccine knowledge, though 3 of the 4 studies were small. But most of these strategies had mixed or no effect on attitudes to vaccines.

Potentially unhelpful strategies

- Scare tactics – such as photos of children with vaccine-preventable diseases. These were largely ineffective; they sometimes backfired and could even increase the perceived risk of vaccine side effects.

- Not acknowledging uncertainty – messages about vaccine effectiveness that did not acknowledge risk, for example. This approach seemed to backfire. In 2 studies it made people more hesitant and reduced their intention to receive a vaccine. Communicating uncertainty, by acknowledging that some information is still unknown, reduced vaccine hesitancy (compared with messaging that did not acknowledge uncertainty).

Why is this important?

The analysis may help public health communicators and policy makers develop strategies to tackle vaccine misinformation and target their communications effectively.

Some studies found that certain strategies were effective among some groups but not others. For example, humorous corrections of misinformation were more effective among people who believed vaccine myths. Those who were more positive about vaccines preferred logic-based messages. This highlights the need to tailor communication strategies depending on the attitude of the audience.

Most of the studies were conducted in the US, which may limit the applicability of the findings to the UK.

What’s next?

The studies in this analysis explored the effect of communications on people’s attitudes and behaviours to vaccination; they did not assess the impact on vaccine uptake. In addition, communication strategies in practice may differ from those in the studies. The researchers suggest that future research could assess communication strategies deployed in the real-world to increase vaccine uptake.

Future studies could explore how to address the spread of misinformation on social media platforms. Online report tools flag misinformation to platforms; research could explore whether such tools reduce the spread of inaccurate information.

You may be interested to read

This summary is based on: Whitehead HS, and others. A systematic review of communication interventions for countering vaccine misinformation. Vaccine 2023; 41: 1018–1034.

Advice from the WHO on having conversations about vaccines.

A guide about dealing with vaccine misinformation from the United Nations Children's Fund.

A communication toolkit about increasing vaccine uptake from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

An e-learning module on how to address online vaccine misinformation from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

Vaccination leaflets, videos, posters, infographics, record cards, stickers and publications from The Health Publications website.

Funding: This study is funded by the NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in Vaccines and Immunisation.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors had no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer: Summaries on NIHR Evidence are not a substitute for professional medical advice. They provide information about research which is funded or supported by the NIHR. Please note that the views expressed are those of the author(s) and reviewer(s) at the time of publication. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

NIHR Evidence is covered by the creative commons, CC-BY licence. Written content and infographics may be freely reproduced provided that suitable acknowledgement is made. Note, this licence excludes comments and images made by third parties, audiovisual content, and linked content on other websites.