This is a plain English summary of an original research article. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and reviewer(s) at the time of publication.

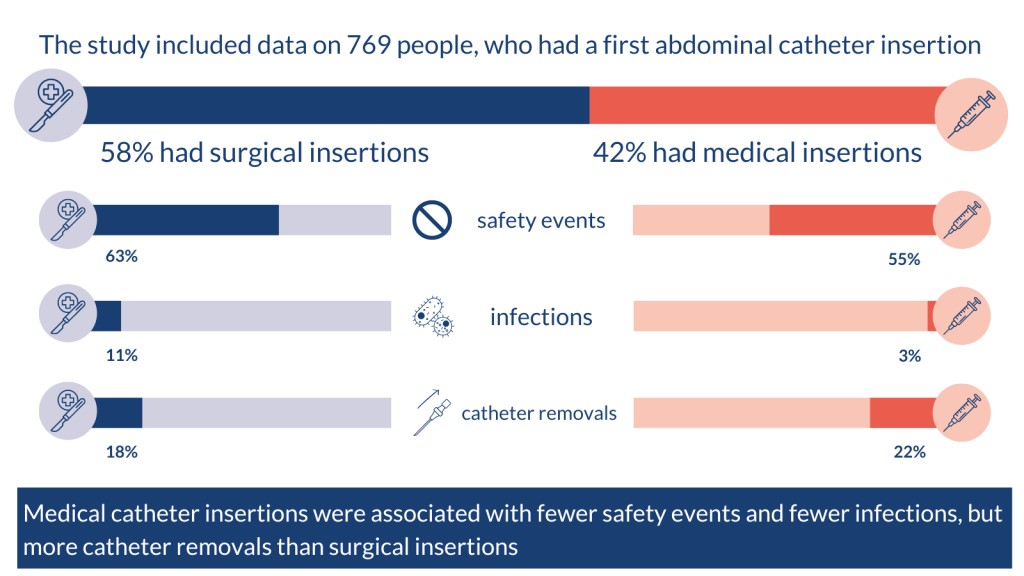

The study included data on 769 people, who had a first abdominal catheter insertion.

58% had surgical insertions. 42% had medical insertions.

Safety events: surgical insertions 63%; medical insertions 55%

Infections: surgical insertions 11%; medical insertions 3%

Catheter removals: surgical insertions 18%; medical insertions 22%

Medical catheter insertions were associated with fewer safety events and fewer infections, but more catheter removals than surgical insertions.

For more information on dialysis, visit the NHS website.

The issue: how safe are medical catheter insertions for dialysis?

People with kidney failure or chronic kidney disease, whose kidneys have stopped working properly, may need dialysis. This therapy takes over the normal function of the kidneys and removes waste products and excess fluid from the blood. Many people have regular dialysis in hospital, where fluids are filtered by a machine (haemodialysis). In peritoneal dialysis, often carried out at home, a catheter is inserted in the abdomen and left there permanently.

A catheter can be inserted under general anaesthetic by a surgeon, or without a general anaesthetic by a physician using a needle (medical insertion). Medical insertions have become more common in recent years due to a lack of access to surgeons and theatre space; they have the advantage of being possible in people who are not well enough to have a general anaesthetic. However, evidence on the safety and efficacy of medical insertions is lacking.

This study assessed the number of safety events following catheter insertions for peritoneal dialysis via the medical and surgical route. Researchers explored the reasons for choosing medical, versus surgical catheter insertions.

What’s new?

The study included data on 769 people, who had a first abdominal catheter insertion. It was carried out at 44 UK dialysis centres from 2015 – 2017. Most people had surgical insertions (58%); the others had medical insertions (42%).

The main outcome was the number of safety events (catheter removal, leak, infection, and further procedures, for instance) 1 year after insertion.

The researchers found that medical insertions were associated with:

- fewer events (55%) than surgical insertions (63%)

- fewer infections (3%) than surgical insertions (11%)

- more catheter removals (22%) than surgical insertions (18%).

Only half of the hospitals in the study offered medical insertions. Hospitals that offered both approaches had better outcomes. People were much less likely to have a medical insertion if they had previous surgery on their abdomen or digestive tract (72% less likely), or cystic kidney disease (88% less likely).

The more experience a hospital had with peritoneal dialysis, the less likely people were to have a safety event.

Why is this important?

Medical insertions had similar or better outcomes than surgical insertions for people on peritoneal dialysis. This study provides reassurance that this is a safe option.

This paper increases confidence in medical insertion for peritoneal dialysis catheters. The medical approach is logistically easier for patients and health care teams than surgical insertion. The medical technique does not require general anaesthesia; it can be used for people who are not well enough to have general anaesthesia and would therefore not be able to have peritoneal dialysis if this technique were not available. Catheter removals were more common with medical insertions, but the researchers say this does not outweigh the convenience of the approach.

Hospitals that offered both approaches had the best outcomes. The researchers suggest this could be because it allows clinicians to decide what approach is best for the patient. They say outcomes could be improved if more hospitals were able to offer both approaches.

Clinicians could consider the advantages of each approach (fewer removals or infections, for example) when deciding which is best for a patient. Avoiding safety events could help people stay on peritoneal dialysis for longer; in this study, most people switched to haemodialysis after an event.

The researchers caution that this study linked surgical insertions with more safety events; it did not suggest that surgical insertions caused the safety events.

What’s next?

This study has implications for the design of catheter insertion pathways for peritoneal dialysis in the UK. It builds on previous evidence that a typically physician-led medical pathway increases access to peritoneal dialysis, with similar or better outcomes. The researchers have discussed the results with NHS England to inform plans for kidney service development.

Physicians may need training to enable them to insert catheters using the medical technique, the researchers say. Those who carry out few medical insertions will need to maintain their expertise, and outcomes will need to be audited to ensure that standards are maintained.

A cost analysis of the two approaches is under review.

You may be interested to read

This is a summary of: Fotheringham J, and others. Catheter Event Rates in Medical Compared to Surgical Peritoneal Dialysis Catheter Insertion. Kidney International Reports 2023; 8: 2635 – 2645.

Easy-read information on peritoneal dialysis.

Easy-read information on kidney failure from the National Kidney Foundation.

Information on taking part in NIHR research on kidney failure.

Funding: The study was funded by the NIHR Research for Patient Benefit programme.

Conflicts of Interest: Several of the study authors have received funding from pharmaceutical companies. See paper for full details.

Disclaimer: Summaries on NIHR Evidence are not a substitute for professional medical advice. They provide information about research which is funded or supported by the NIHR. Please note that the views expressed are those of the author(s) and reviewer(s) at the time of publication. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

NIHR Evidence is covered by the creative commons, CC-BY licence. Written content and infographics may be freely reproduced provided that suitable acknowledgement is made. Note, this licence excludes comments and images made by third parties, audiovisual content, and linked content on other websites.