This is a plain English summary of an original research article. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and reviewer(s) at the time of publication.

People with cancer of the oropharynx (the middle part of the throat) are normally tested for a protein called p16. New research suggests that an additional test for the human papillomavirus (HPV) could give more accurate prognoses, and influence treatment.

Oropharyngeal cancers caused by HPV tend to respond better to treatment than those whose cancer has a different cause. People are more likely to survive, and may need less intense treatment. However, testing for HPV is expensive. Therefore, people are usually tested instead for the protein p16, which increases in cancer cells when HPV is present. Most people with oropharyngeal cancer either test positive for both p16 and HPV, or negative for both.

Some people have discordant oropharyngeal cancer, which means they test positive for one but not the other (either HPV or p16). This study analysed 13 studies involving more than 7,600 people. Researchers investigated how common discordant oropharyngeal cancer is, and looked at people’s survival.

Almost 1 in 10 oropharyngeal cancers were discordant in this review. People with discordant cancer had better survival than people who tested negative for both p16 and HPV; they had worse survival than people who tested positive for both.

The researchers recommend that people with oropharyngeal cancer receive a test for HPV, along with the standard p16 test. This could improve their surgeons’ ability to estimate life expectancy, and impact treatment decisions.

More information about head and neck cancer is available on the NHS website.

The issue: should we test oropharyngeal cancers for HPV as well as p16?

Oropharyngeal cancers include cancers of the soft palate (back roof of the mouth), the side and back walls of the throat, the tonsils, and the back third of the tongue. These cancers are becoming increasingly common around the world. HPV is an important cause. People with oropharyngeal cancer caused by HPV respond better to treatment and survive longer than those whose cancer is unrelated to HPV.

Testing for HPV directly is difficult and costly. A protein called p16 usually increases in cancer cells when HPV is present. Testing for p16 is easier than for HPV and is routinely carried out instead. However, p16 is not a perfect marker for HPV. Some people who test positive for p16 do not have HPV-related cancer. Others, who test negative for p16, have HPV-related cancer. This is discordant oropharyngeal cancer.

This study sought to find out how common discordant oropharyngeal cancer is, and how long people survive.

What’s new?

The review included studies on oropharyngeal cancer carried out since 1970. All had at least 100 participants. The analysis (based on 13 studies from 8 European countries and 1 from Canada) involved more than 7,600 people with oropharyngeal cancer. Participants’ average age was 60 and most were men (75%).

The researchers found that almost 1 in 10 (9%) had discordant cancer. Roughly half tested positive for p16 but not HPV (5%); slightly fewer (4%) tested negative for p16 but positive for HPV.

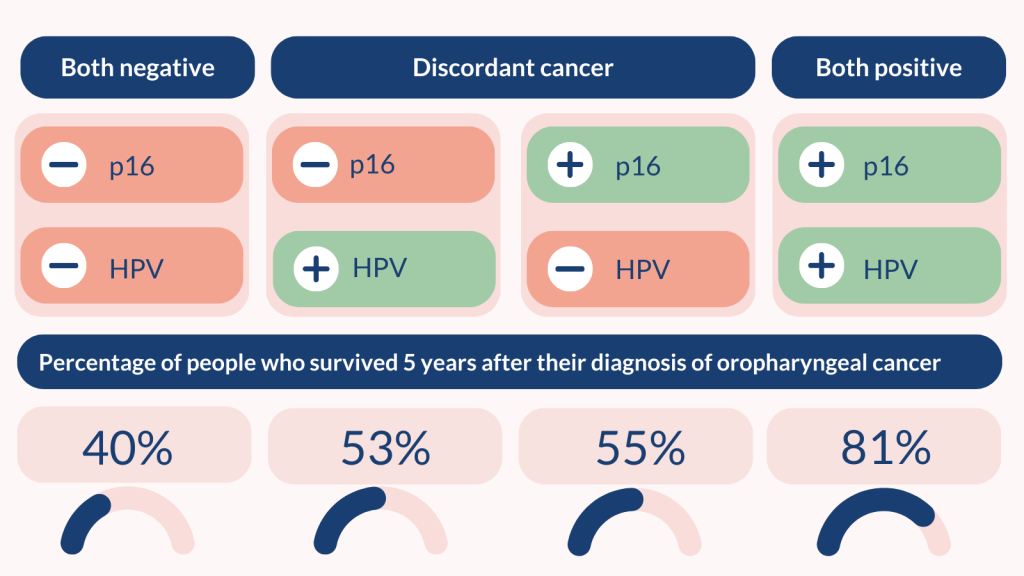

In studies including 6,882 people, 5 years after testing:

- 81% of those who tested positive for p16 and HPV survived

- 53 – 55% of those with discordant cancer survived

- 40% of those who tested negative for both p16 and HPV survived.

The research team found the same pattern for survival with no recurrence of cancer (in 6,765 people).

People who smoked were less likely to survive. People with discordant oropharyngeal cancer who had never smoked had similar survival to people who tested positive for both p16 and HPV. Those who smoked were half as likely to survive (similar to people who tested negative for p16 and HPV).

Why is this important?

This is the largest analysis of its kind, the researchers say. It found that almost 1 in 10 oropharyngeal cancers are discordant. People with discordant cancer have better outcomes than people who test negative for p16 and HPV, but worse than those who test positive for both. This information will inform discussions between doctors and people with oropharyngeal cancer about their treatment plan, and likely survival.

What’s next?

HPV testing is available in some NHS centres but not all. The researchers recommend that people with oropharyngeal cancer should be tested for HPV, along with the standard p16 test. Testing for both would allow clinicians to provide people with accurate predictions of their survival. About 1 in 10 will have discordant cancer.

In current trials, people with oropharyngeal cancer are often tested only for p16. Those with HPV-related cancer may be able to receive less intense treatment than other people, because they respond better; this minimises the negative effects of treatment. People with discordant cancer who test negative for p16 (but have HPV-related cancer) may benefit from less intense treatment, but do not receive it.

The researchers recommend testing for HPV as well as for p16 in order to inform decisions about the intensity of treatment in clinical trials and practice. The researchers say Ear, Nose and Throat UK guidelines may need to be updated to reflect the survival data found for people with discordant oropharyngeal cancer.

You may be interested to read

This summary is based on: Mehanna H, von Buchwald C, and others. Prognostic implications of p16 and HPV discordance in oropharyngeal cancer (HNCIG-EPIC-OPC): a multicentre, multinational, individual patient data analysis. Lancet Oncology 2023; 24: 239 – 5.

Information about oropharyngeal cancer from Cancer Research UK.

Educational materials about head and neck cancer from the Oracle Trust.

Information on taking part in NIHR oropharyngeal cancer studies.

Funding: The lead author is an NIHR senior investigator.

Conflicts of Interest: Several of the study authors have received funding from pharmaceutical companies that produce cancer drugs. See paper for full disclosures.

Disclaimer: Summaries on NIHR Evidence are not a substitute for professional medical advice. They provide information about research which is funded or supported by the NIHR. Please note that the views expressed are those of the author(s) and reviewer(s) at the time of publication. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

NIHR Evidence is covered by the creative commons, CC-BY licence. Written content and infographics may be freely reproduced provided that suitable acknowledgement is made. Note, this licence excludes comments and images made by third parties, audiovisual content, and linked content on other websites.