Breast cancer is the most common cancer in the UK and every year, around 56,000 people are diagnosed with it. That’s around 150 women a day. The causes are not fully understood, but research is expanding our knowledge about the risk factors.

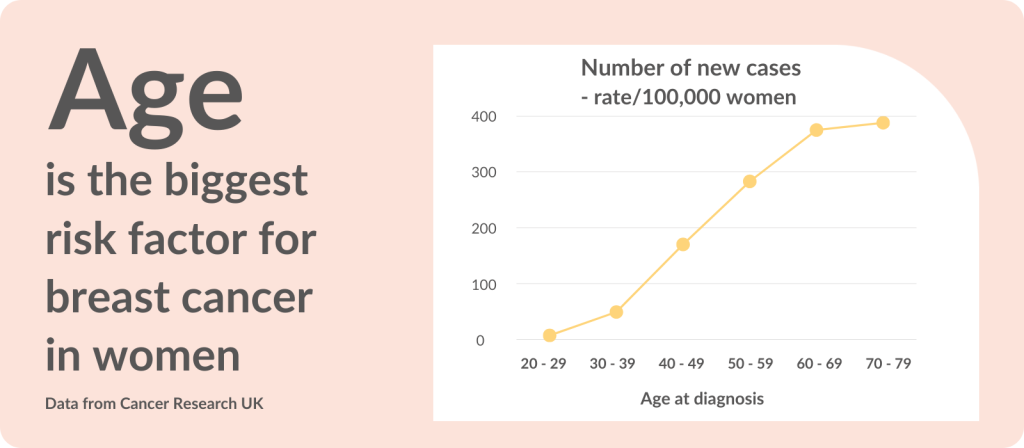

Age and biological sex have the greatest impact: 8 in 10 breast cancers are in women over 50. The NHS Breast Screening Programme therefore automatically invites women every 3 years between the ages of 50 - 71; this is the age group most likely to benefit.

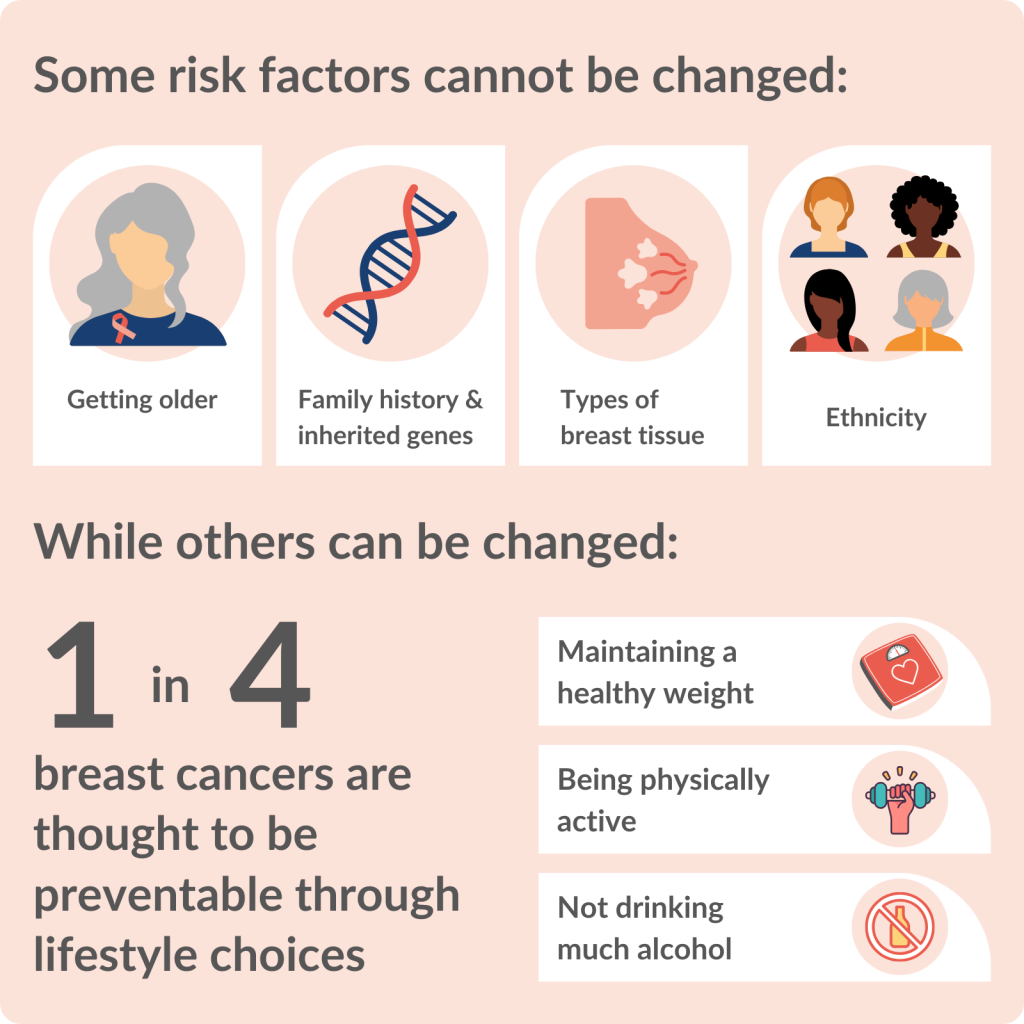

But some women are at increased risk because of their family history, genes, breast type or ethnicity - factors they cannot change. Alongside these factors, aspects of lifestyle, such as weight and alcohol consumption, also feed into a woman’s overall risk.

For the future, the UK’s National Screening Committee is considering risk-based screening. Ongoing discussions are exploring the possibility of routine breast screening based on someone’s individual risk, rather than just their age. This could increase the benefits and reduce the harms of screening. More research is needed before this can happen. For example, how often could women at low risk be screened? Would risk-based screening increase inequalities?

But with such changes on the horizon, now more than ever, women need to understand their breast cancer risk. Many will find the concepts and statistics difficult to relate to. Effective communication will be challenging.

Healthcare professionals will need to establish women's risk, explore how they perceive the risk and then have informed discussions about how to reduce it.

This Collection brings together insights from examples of NIHR research. Most of the research has been highlighted in accessible summaries – NIHR Alerts. The information will be useful for GPs and other healthcare professionals involved in commissioning and delivering services. Members of the public may also be interested.

Key messages

1. Age and lifestyle can increase breast cancer risk

Overall, age is the main risk factor. The NHS Breast Screening Programme for women over 50 continues to prevent deaths from breast cancer, with the benefits outweighing the risks of over-diagnosis. However, it may save more lives if it were extended to include younger women. Alongside screening, lifestyle is important. Women considering short-term hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for symptoms of the menopause can be reassured about the risk of breast cancer. But obesity and overweight can be responsible for breast cancers; maintaining a healthy weight would prevent some cases.

2. Family history and genes greatly increase some women’s risk

Long-term research shows that some women with a family history of breast cancer are more likely to survive if they receive enhanced screening (such as more frequent invitations). Those at high risk may be eligible to take a genetic test; even so, answers are not clear-cut. Research found that estimates of risk based on combinations of genes need to take ethnicity into account. Those at the highest risk may be offered surgery to remove their breasts. This effectively reduces the risk of cancer, but many women delay having the procedure. More support to make an informed choice could encourage some women to consider the option sooner.

3. Good communication could help women act on their risk

Women compare themselves with affected relatives to make sense of their own risk of breast cancer. Healthcare professionals need to find out and acknowledge how women judge their own risk. Women at higher risk need to be more aware of non-lump symptoms, such as nipple rash.

Introduction: What is breast cancer risk?

Determining someone’s risk of developing cancer is difficult. Everyone is different, and many factors combine to give someone’s overall cancer risk.

Some risk factors can be changed, and some cannot. Risk factors we cannot alter include biological sex at birth, inherited genes and ethnicity. However, nearly 1 in 4 breast cancers (23%) are thought to be preventable through lifestyle choices, such as maintaining a healthy weight, being physically active and avoiding alcohol.

Women who understand their risk of breast cancer, can make informed decisions about their health and habits. This could reduce their risk of developing the disease and increase the chance of finding it early when treatments are most effective, by being breast aware and attending regular screening, for example.

Discussing risk in a way people understand is vital. But most (6 in 10) adults struggle with information that includes numbers and statistics. Risks need to feel relevant, and healthcare professionals need to consider using a mix of numbers and pictures. There are best practice guides available, and a previous NIHR Evidence Collection has discussed how to make health information accessible, inclusive and appropriate.

1. Age and lifestyle can increase breast cancer risk

Younger women could benefit from breast screening in future

Age is the main risk factor for breast cancer: the older a woman is, the more likely she is to develop breast cancer. The NHS Breast Screening Programme is based on age. Screening is offered to women every 3 years between the ages of 50 to 71. Recently published research reaffirmed that the NHS programme continues to prevent deaths from breast cancer and that the benefits outweigh the risks of over-diagnosis (finding cancers that would never have caused the woman harm). Approximately 9 breast cancer deaths were prevented for every 1,000 women who attended screening aged 50 – 69 years.

Screening can prevent breast cancer deaths but there is uncertainty whether it reduces deaths by any cause (all-cause mortality). This is difficult to assess; people die for many reasons other than breast cancer. Some research has shown a small reduction (nearly 2%), whereas others found no effect.

Women in their early 50s are more than twice as likely to develop breast cancer, compared to those in their early 40s (incidence rate of 28, compared to 12, per 10,000 women). Even so, around 7,500 women in their 40s are diagnosed with breast cancer every year in the UK.

There is long-standing debate about the possible benefits and harms of screening younger women. To help resolve the issue, a long-term study involving more than 160,000 women looked at the impact of annual breast screening for women in their 40s. Women offered screening were 25% less likely to die of breast cancer in the first 10 years of the trial. Approximately one death was prevented for 1,000 women screened. The risk of over-diagnosis was not higher among these younger women. This suggests that extending the screening programme to include women in their 40s may save lives and would not increase its harms. A large study involving 4 million women will provide further evidence to the debate.

A key question relevant to screening women in their 40s, is whether screening can be better targeted. Some women are at higher risk… because of their family history or germline genetic mutations or because they have dense breast tissue. If screening could be targeted to women at higher risk, and if it could capture more of the aggressive cancers that could lead to the patients’ premature death, then it would become more cost-effective.”

David Cameron, Professor of Medical Oncology, University of Edinburgh

Women on HRT can be reassured about the risk of breast cancer

When women are first invited for routine breast screening (aged about 50), many will be going through the menopause.

The menopause often comes with unpleasant symptoms such as hot flushes and changes in mood. Many women take hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to relieve these symptoms. They may be concerned that HRT could increase the risk of breast cancer. Recent research, which included more than half a million women, provides reassurance.

It found that HRT is generally linked to only small increased risks of breast cancer. For example, using HRT for less than 5 years would be linked to 9 extra cases of breast cancer in a group of 10,000 women in their 50s. That is less than one in a thousand women.

HRT taken for less than a year did not increase risk of breast cancer. Risks increased with the duration of HRT treatment and were noticeably higher if taken for longer than 5 years. But the risk declined once the HRT was stopped. The type of progestogen in combined HRT also made a difference. As did a woman’s age: those in their 50s were at lower risk than those in their 60s and 70s. The findings could inform discussions between doctors and women considering HRT.

“This evidence is mostly consistent with what is already known. However, it is unique because it uses databases that are largely representative of the general population in the UK. In addition, it explored age-specific estimates of excess breast cancer risk with the different types of HRT. This could lead to more informed decisions about HRT use. This work will help me when discussing HRT with my patients.”

Mangesh Thorat, Consultant Surgeon, Guy's Hospital, London

Healthy weight would prevent some breast cancers

In the UK, almost 2 in 3 adults are living with obesity or overweight. This increases the risk of many different types of cancer. Overweight and obesity also increase the risk of type 2 diabetes, which in turn increases the risk of some cancers. A large study estimated the impact of being overweight or having diabetes, individually and together, on cancer risk, including breast cancer. It used data from more than 14 million cases of 12 different cancers worldwide.

A high body mass index (BMI) was responsible for 7 in 100 (6.9%) breast cancers, and diabetes was responsible for 2 in 100 (2%) cases in women who had gone through the menopause. This finding is in line with other research which has shown that maintaining a healthy weight would prevent some breast cancers.

2. Family history and genes greatly increase some women’s risk

Women have a higher risk of developing breast cancer if close relatives have had the disease. NICE guidelines classify women with a family history of breast cancer into 3 groups: those whose risk of developing breast cancer over their lifetime is similar to the general population (less than 17%), those with moderate risk (17-29%), or high risk (30%+).

Someone’s cancer risk takes into account their family history, along with alcohol intake, use of HRT, previous pregnancy and breastfeeding, genetic tests if available, and other factors. Those with a moderate or high risk are eligible for extra breast screening, starting at a younger age than the NHS Breast Screening Programme and continuing for longer on a yearly basis (rather than every 3 years). People at high risk may also be offered drugs to prevent breast cancer or surgery to remove breasts (mastectomy).

Extra screening improves survival

A 30-year study explored the yearly screening offered to women at moderate or high risk of breast cancer and provided reassurance that this strategy is effective. It involved 14,000 women at increased risk due to their family history; over the course of the study, 649 (5%) developed breast cancer. The research showed that, 10 or 20 years after diagnosis, women at increased risk who received enhanced screening were more likely to be alive than other women in England with breast cancer.

Genetic tests need to consider ethnicity

Women with a strong family history of breast cancer may be eligible for a genetic test to further understand their risk. Genetic tests can identify altered genes, such as faulty versions of the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene. Around 7 in 10 (70%) of women with one of these altered genes will develop breast cancer. Women may also have versions (variants) of genes that each increase their risk of breast cancer only slightly, but a combination could put them at high risk overall.

Researchers have developed assessments called polygenic risk scores (such as SNP18 and SNP143) which combine the risks of genetic variants. These scores effectively predict the risk of breast cancer in women of White European origin. However, a recent study, involving over 9000 women, found they exaggerate the risk for women in other ethnic groups, especially Black and Jewish women. An overestimate of risk could cause unnecessary anxiety and lead to excessive screening or preventive drug and surgical treatments. Ethnicity needs to be taken into account when using the tests, the researchers say.

“These findings show you can’t simply apply polygenic risk scores derived from White Europeans in people of other ethnicities. Black, Asian, mixed-race and Jewish women in the UK might buy commercial tests that could exaggerate their risk of the disease. This may frighten them and lead to unnecessary screening and other interventions they don’t need.”

Gareth Evans, Professor of Medical Genetics and Cancer Epidemiology, the University of Manchester

Risk-reducing surgery is effective but women delay

Women with a positive test for a faulty BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene have a greatly increased risk of breast cancer and may be offered risk-reducing surgery to remove their breasts. Recent research explored whether, and when, women chose to have the surgery. It also looked at the effectiveness of the surgery in preventing breast cancer. A total of 887 women with a faulty BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene took part.

The study found that, 20 years after their test result, more than half (58%) of the women had had their breasts removed. Surgery reduced the risk of breast cancer by 94%, but women delayed the procedure by an average of two years after the test, and sometimes much longer. It is a difficult decision for women to make. Surgery effectively reduces the risk of cancer but could have physical, mental and emotional consequences. More support for women at high risk could support them to make an informed choice; this could encourage some to consider the option sooner.

“I personally know the difficulties of cancer treatment, so the benefits of risk-reducing surgery are clear to me. Instead of seeing risk-reducing surgery as a necessary evil, I see it is a means of women retaining control over their future. Perhaps cancer patients could be the best advocates.”

Davida Hamilton, Public Contributor, West Yorkshire

3. Good communication helps women act on their risk

Women at increased risk of breast cancer need to understand what this means so they can make decisions with their doctor about preventive actions. The way women think about risk can affect their decisions, and needs to be addressed by doctors to avoid misunderstandings.

Women look to family to judge their risk

A recent review found that women at moderate or high risk often compare themselves to affected relatives to make sense of their own risk. One participant said, “I feel like it’s just, it’s going to happen because I have the same breasts as my mum”. They could find it difficult to accept a clinical risk estimate which differed from their own view. Another woman said, “But these are just statistics and I can’t really go by statistics, you know?” The mismatch can affect the doctor-patient relationship and lead women to doubt preventive advice.

Women at higher risk need to be aware of symptoms

Healthcare professionals need to find out and acknowledge how women judge their risk of breast cancer. They also need to ensure women at higher risk know what symptoms to look for. Recent research involving over 400 women highlighted a lack of knowledge about non-lump symptoms, such as nipple rash and skin redness, especially among women with less education and lower socioeconomic status. This suggests that these groups need targeted support.

Conclusion

Family history, genes, breast type or ethnicity can increase women’s risk of breast cancer. Aspects of lifestyle, such as weight and alcohol consumption, also feed into a woman’s overall risk.

Women at higher risk of breast cancer because of their family history or inherited genes may be invited for extra screening. However, routine NHS breast screening is based on women’s age alone. The UK National Screening Committee is considering how to approach the challenge of risk-based screening for the future.

This could change the age at which women are invited, how often they are invited and what screening tests are offered. The NIHR has funded several key projects to inform the debate, including an estimate of the cost-effectiveness of the approach and an assessment of the feasibility of implementing a personalised risk score into a woman’s first screening appointment and the impact on women, NHS staff and others.

The findings show promise. Women were not more anxious or worried by the new approach, and it was successful in encouraging high-risk women to take preventative medication to reduce their risk of developing breast cancer. However, questions remain. For example, will this approach increase inequalities in screening? What will the role of primary care be? How often could women at low risk be screened? Large ongoing trials such as MyPeBS, involving 85,000 women, should provide answers.

Any move to risk-based screening reinforces the need for professionals and the public to know more about breast cancer risk. They need to understand the risk factors themselves, how women perceive and act on information about risk, and how successful interventions to reduce risk are.

This will help healthcare professionals support women and enable them to make informed decisions. The examples of research highlighted in this Collection provide evidence towards that goal.

Author: Jemma Kwint, Senior Research Fellow, NIHR Evidence

How to cite this Collection: NIHR Evidence; Why we need to understand breast cancer risk; September 2023; doi: 10.3310/nihrevidence_60242

Disclaimer: This Collection is based on research which is funded or supported by the NIHR. It is not a substitute for professional healthcare advice. Please note that views expressed are those of the author(s) and reviewer(s) at the time of publication. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

NIHR Evidence is covered by the creative commons, CC-BY licence. Written content and infographics may be freely reproduced provided that suitable acknowledgement is made. Note, this licence excludes comments and images made by third parties, audiovisual content, and linked content on other websites.