“Diabetes, of all types, is a condition of self-management that places huge demands on people’s time, energy and cognitive resource. Preventing the development of type 2 diabetes also requires significant and sustained action from the individual.”

Lucy Chambers, Head of Research Communications, Diabetes UK

Diabetes is a serious, life-changing condition in which people have too much sugar in their blood. Long-term complications may include sight loss, kidney disease, amputations, heart disease and stroke. Type 1 diabetes cannot be prevented, but type 2 diabetes often can: a healthy weight and lifestyle greatly reduce a person’s risk.

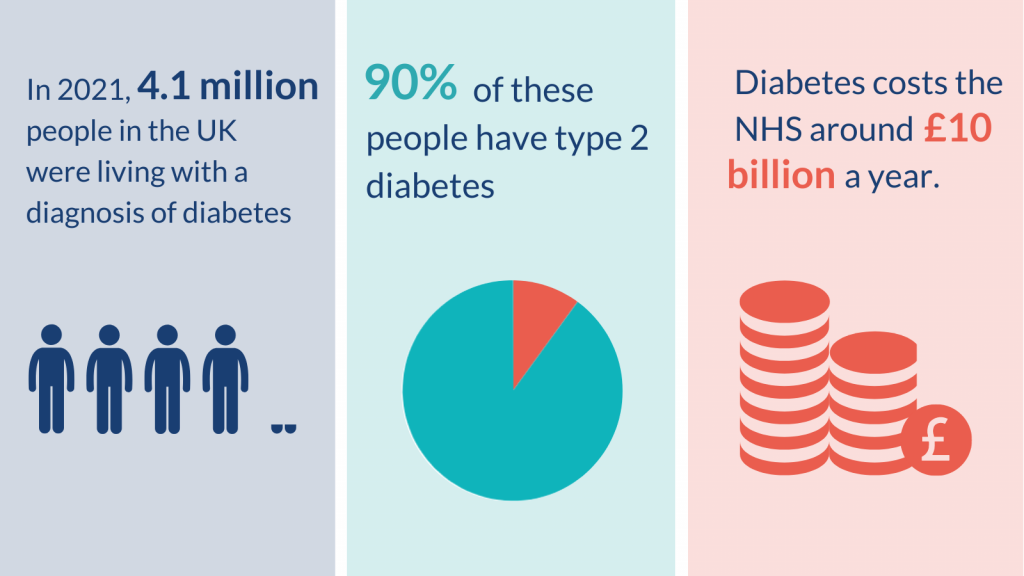

Diabetes costs the NHS around £10 billion a year. It is a national priority and a focus of the NHS Long Term Plan. There are guidelines on diabetes management and NHS policy highlights the need for more person-centred care. This includes supporting people, and giving them the tools they need, to manage their own health. However, there are large inequalities in access to services across the country.

Preventing type 2 diabetes, and managing both type 1 and type 2, requires life-long commitment, but the potential health gains are huge. Placing people at the heart of services can improve their engagement, health outcomes and experiences. Research can reveal ways to support this goal for diabetes care.

This Collection brings together messages from research highlighted in accessible summaries - NIHR Alerts - over the past couple of years. It illustrates how taking account of individuals’ needs, differences and wishes could improve diabetes services. We hope it provides useful information both for those commissioning and delivering services, and for members of the public.

A growing health crisis

Many people are at risk of, or are living with diabetes. The numbers are increasing rapidly; diagnoses have doubled in the last 15 years. In 2021, 4.1 million people in the UK had a diagnosis of diabetes; 90% had type 2. This is an increase of more than 150,000 since 2020. A further 1 million people have no diagnosis but also have type 2 diabetes. Still more, an estimated 13.6 million people, are at risk of developing type 2 diabetes. However, up to half of these people could prevent or delay diabetes through lifestyle changes such as sustained weight loss and physical activity.

Obesity is the greatest risk factor for type 2 diabetes. The increasing number of people with obesity is driving the rise in type 2 diabetes. Other risk factors include age, ethnicity, a family history of diabetes, and inactivity. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) estimates that by 2025, more than 5 million people in the UK will be diagnosed with diabetes.

Diabetes puts people at increased risk of serious health complications including eye, foot and kidney problems, heart disease, stroke and dementia. It also increases the risk of dying with COVID-19.

“Diabetes is common, affecting almost 1 in 10 people in much of the UK. Diabetes impacts individuals and families, increases hospital admissions and premature death and consumes 10% of the entire NHS budget."

Kevin Hardy, Consultant Diabetologist, St Helens and Knowsley Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

How to increase participation in type 2 diabetes prevention programmes

Diabetes prevention programmes can reduce the risk of developing the condition, but engaging people is challenging. Programmes are for people with prediabetes. This means their blood sugar is above target range, but not at the threshold for a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. The aim of the programmes is to promote healthy eating, a physically active lifestyle and weight loss.

The NIHR is carrying out an independent assessment of the NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme for England, ‘Healthier You’. Signs are encouraging that people who complete the programme reduce the amount of sugar in their blood and lose weight. However, many people never start the course, or do not complete it.

Analyses of the first 100,000 referrals to ‘Healthier You’ found that just over half of those referred took up a place. Only 1 in 5 completed the 9-month programme. There was large variation across the 4 course providers. Certain groups were less likely to participate: those who are employed, have a disability, are younger, from more deprived areas and some ethnic minority communities. Measures are needed to increase participation among people in these groups.

More out-of-hours sessions may improve retention. Digital (online) diabetes prevention programmes are now available and could reach working-age people. Researchers are currently comparing digital to face-to-face programmes. NHS England recently introduced new targets to refer and retain proportionally more participants from ethnic minority groups and deprived areas. It is not yet known whether this will increase participation among these groups.

The same research team has also described people’s experience of Healthier You. This was more negative when information was difficult to understand. The study recommended greater use of interactive and visual activities including worksheets, posters and food models. Groups larger than 15 people were also off-putting; the research suggested that smaller group sizes could help keep people in the programme.

“Trying to encourage and engage people into participating in prevention programmes is always difficult as so many have the attitude 'it won't happen to me'. Getting across the seriousness of diabetes is difficult, because for many who live with type 2, you don't always feel unwell. So hearing the awful complications that may happen can be hard to accept.”

Angelina Whitmarsh, Public Contributor, Southampton

Diabetes prevention should be guided by people’s ethnic group

Body weight is closely linked to the chances of developing type 2 diabetes, but has different effects on different groups of people. NICE guidance currently recommends action to prevent type 2 diabetes for people with a body mass index (BMI) of 30. In Black African, African-Caribbean, South Asian and Chinese groups, prevention should start at a BMI of 27.5. Research has now found that some ethnic groups would benefit from access to prevention services at a much lower BMI than is currently used.

The study was large enough to look in detail at South Asian and Black populations. It suggested that diabetes prevention is needed at BMI values as low as 21 to 24 for different South Asian populations, and 26 to 27 for some Black populations. A more personalised approach to prevention could mean triggering action sooner. It could prevent many people in these populations from developing type 2 diabetes.

Access to personal health records supports diabetes self-care

Keeping blood sugar levels in the target range is central to diabetes self-care. People need to understand and actively manage their own condition. Access to their medical records can help.

Electronic health records are not routinely shared with patients in the UK. However, research found that sharing data helped people with diabetes reduce their blood sugar levels. It also improved medicines safety and often reduced people’s need for healthcare. Increasing access to personal health records could bring real benefits to individuals managing their diabetes. Further research is needed to address digital health inequities among people with lower education level or literacy, for example.

Targeted services could help those with greatest need

A new Diabetes Severity Score is based on data routinely collected during regular check-ups for people with type 2 diabetes. Research suggests that this score may be better at identifying those most in need of support than the current commonly used blood test. A higher score was linked to increased risk of hospital admission or death. The score could inform decisions about individual patients’ care and could help direct NHS funds to those who need it most.

Individuals with type 2 diabetes fall into different clusters, based on their clinical measurements (e.g. BMI, waist circumference, production of insulin). Research has identified 4 sub-groups among people from India, 2 of which were linked to an especially high risk of kidney and eye disease. People of Indian heritage are at increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes, and at a younger age, than people from other backgrounds. This research could allow people with the highest risk of complications to be offered more intense treatment.

Current guidelines for the management of type 2 diabetes do not discuss disease severity or clinical sub-group. Consideration of these factors could in future help improve management of the condition and ensure interventions are tailored to individuals.

Listening to young people could improve their engagement with services

More and more children and young people are living with diabetes. In the UK, 9 in 10 younger people with diabetes have type 1, but type 2 is becoming more common. These young people need to engage with diabetes services and be empowered to manage their condition. However, young people miss more health appointments than other age groups, with those from disadvantaged or ethnic minority communities most likely to miss appointments and be considered ‘disengaged’ by their clinician.

New research on how to improve engagement with services highlights the importance of listening to young people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes to find out what is important to them. It suggests that discussions need to be frank and honest. Diabetes appointments need to pay as much attention to young people’s lifestyles, behaviour and identity as to their blood sugar levels. Professionals could use the information to aim for more realistic blood sugar targets.

Fewer foot checks for people at low risk of ulcers

High blood sugar levels can seriously damage parts of the body, including eyes and feet. Attending regular diabetes health checks can prevent or delay these complications.

NICE guidance estimates that 1 in 10 people with diabetes will have a diabetic foot ulcer (an open wound on the foot) at some point. Foot ulcers can lead to foot and leg amputations, and to early death. However, they can be prevented by monitoring risk, and by wearing specialised shoes and insoles to reduce pressure on the foot.

Monitoring the risk of foot ulcers can be complex. UK guidance currently recommends that professionals use 8 to 10 tests for nerve damage or infection, which increase the risk of an ulcer. A new simple, cheap and accurate tool is based on only 3 pieces of information, all of which are routinely gathered during foot examinations. The tool gives a risk score that could identify both the people who would benefit most from preventive treatment, and those who might need less monitoring.

The same researchers found that for people at low risk of ulcers, it may be acceptable to carry out foot health checks every 2 years (rather than every year, as is currently done). This would reduce the number of face-to-face contacts for patients and could free up resources for those who need them most. NICE is considering these new findings in the planned update of its guideline.

People at moderate or high risk of developing ulcers may need specialised footwear to relieve pressure on the feet during everyday activities. Shoes and insoles are widely available, but products vary. A study identified certain features that were effective in reducing pressure on the foot. They included arch supports, cushioned cut-outs around sites at risk of damage, and cushioning to reduce pressure on the ball of the foot. These features should be incorporated as standard. The researchers recommend that designers of insoles and bespoke shoes use techniques for measuring pressure on the feet of people with diabetes.

Conclusion

Diabetes is one of the fastest-growing health challenges of the 21st century. It requires constant self-management and regular contact with healthcare services throughout life. Effective ways to prevent type 2 diabetes, and to manage type 1 and type 2, are available. But more needs to be done to understand how to engage people with services, and how to target care to those who need it most.

This Collection provides examples of how taking account of individuals’ needs, differences and wishes, can help. Offering prevention services at lower BMIs for people from certain ethnic groups could prevent type 2 diabetes in some. People would be more likely to stay in prevention programmes if course materials were engaging and group sizes below 15. Young people would be more likely to engage with diabetes services if their life priorities were given as much attention as their blood sugar levels. Increasing access to personal health records could help people self-manage their blood sugar levels. Using personal risk scores to identify people at high risk of complications or worsening health could help provide targeted care.

Diabetes care is complex. It requires personal commitment and NHS resources. This Collection provides examples of NIHR research that demonstrate the efforts being made to improve the services on offer. Above all, it highlights that ‘one size does not fit all’. Every individual should be kept at the very centre of their own care.

You may be interested

In addition to the examples highlighted as part of this Collection, many other NIHR-funded studies into diabetes are published or ongoing.

How to cite this Collection: NIHR Evidence: Diabetes: putting people at the heart of services; July 2022; doi: 10.3310/nihrevidence_52026

Author: Jemma Kwint, Senior Research Fellow (Evidence), NIHR

Disclaimer: This publication is not a substitute for professional healthcare advice. It provides information about research which is funded or supported by the NIHR. Please note that views expressed are those of the author(s) and reviewer(s) at the time of publication. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

NIHR Evidence is covered by the creative commons, CC-BY licence. Written content and infographics may be freely reproduced provided that suitable acknowledgement is made. Note, this licence excludes comments and images made by third parties, audiovisual content, and linked content on other websites.