Public involvement in research can enhance its reach, quality, and impact. Members of the public are often actively engaged in the early stages of the research cycle, in study design, for example. But in the latter stages, including dissemination of results and implementation, public involvement can be neglected.

In this Collection, we argue that working with members of the public throughout the research cycle supports effective knowledge mobilisation. The Collection includes practical advice about how to do this and highlights key points raised in a recent NIHR webinar (Mobilising research knowledge with members of the public: The challenges and opportunities). It combines insights from research and practice. The information will be useful for researchers and members of the public working together to co-produce research, mobilise and implement findings, and demonstrate impact.

This is the first in a series of Collections, which will bring together best evidence and practice in knowledge mobilisation.

Why does knowledge mobilisation matter?

Knowledge mobilisation supports creation of new knowledge, effective sharing of research findings (dissemination) and delivering impact (the demonstrable benefit of research). Good knowledge mobilisation contributes to:

- study design; research questions are relevant to practice and everyday life

- dissemination; answers are shared with the people who need to know

- implementation; findings drive changes to policy and practice

Dissemination

Targeted distribution of knowledge to specific audiences using planned strategies

Knowledge mobilisation

The process that paves the way to impact being realised by actively bringing stakeholders together throughout the research cycle to share, respond to, and act upon research plans and findings.

Implementation

The practical process of integrating new practices or products into everyday practice

Impact

The demonstrable contribution that research makes to society and the economy, benefiting individuals, organisations and nations.

Patients and the public contribute to knowledge mobilisation

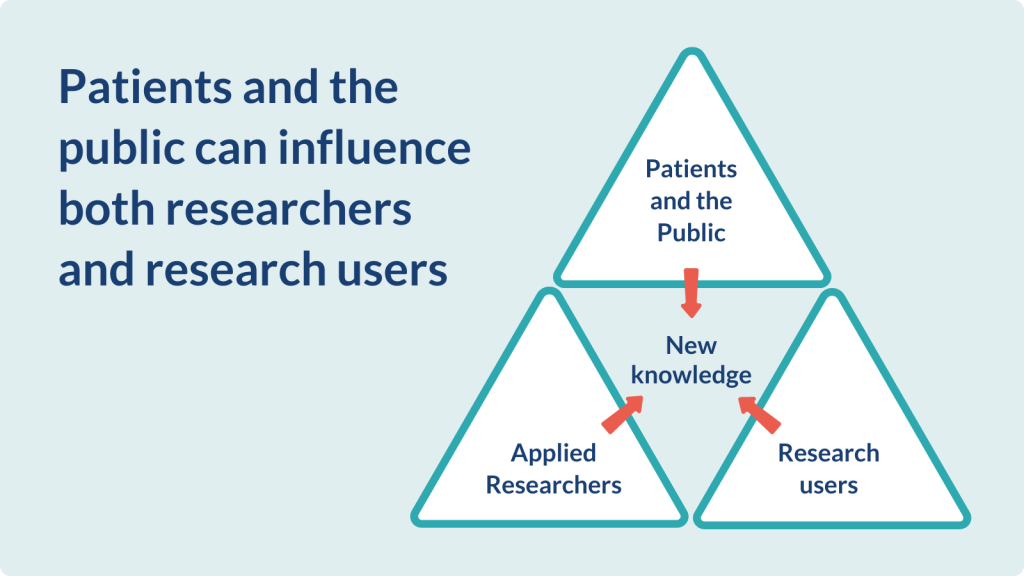

Patients and the public can influence both researchers and research users (including professionals, and other patients and members of the public). They are an integral part of the supportive partnership necessary for effective knowledge mobilisation. Public involvement in research has been shown to enhance its reach, quality, and impact*. Public contributors within knowledge mobilisation processes help to align research with the needs of research users and to co-produce and mobilise knowledge.

*(Chalmers, Glasziou 2009; Staniszewska et al, 2013; Ocloo 2016; Maguire, Garside, 2019)

Triad Structure adapted from R Lilford, ARC West Midlands

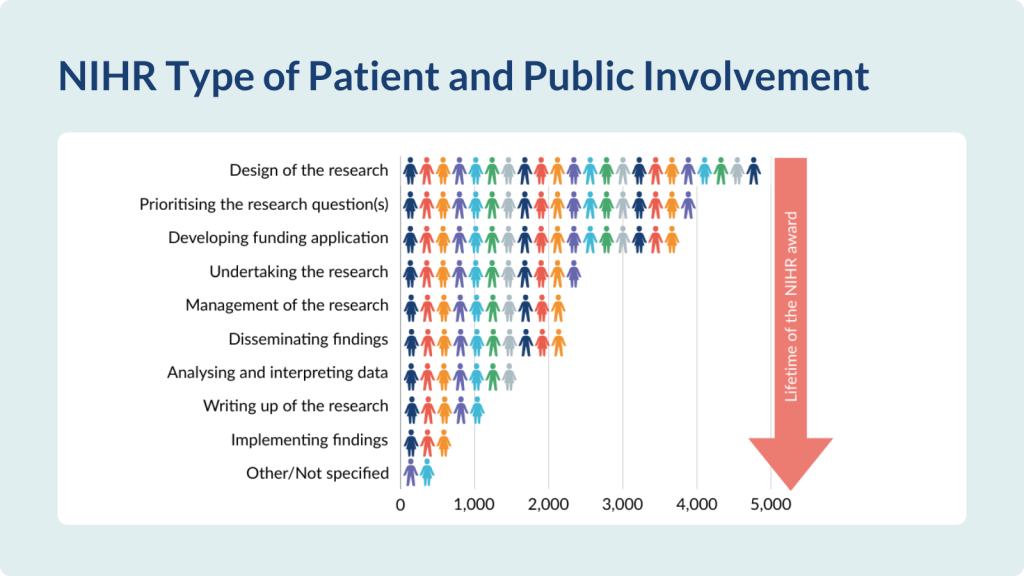

A review of 17 NIHR-funded studies showed that public involvement is widely used in the early stages of the research cycle: setting research priorities, in study design and development, writing lay summaries, and contributing to advisory group meetings. However, in the latter stages of research, including dissemination and implementation, public involvement is often neglected.

Last year, 30% of NIHR-funded studies reported the involvement of patients and the public in dissemination activities and only 11% reported their involvement in mobilising study findings for implementation (researchfish data). This trend is similar to other funders. Involving patients and the public in research is a requirement for NIHR.

Graph from 'Reporting the outputs, outcomes and impacts of NIHR research 2023 update'

Researchers and practitioners may be 'missing a trick’ by not working with members of the public to mobilise research knowledge across organisational and other boundaries. Recognition is growing that the public can facilitate the implementation of research evidence. This has led to calls to increase the involvement of patients and members of the public in knowledge mobilisation. Public contributors are keen to help.

“The public needs to be embedded in the implementation of any research and encouraged to help mobilise the knowledge. If the public understands the research findings, they can offer practical and realistic advice on how it can be used to benefit themselves and everyone else in the real world. Surely this is why research is carried out in the first place.

Patients and public members are here to help with implementation – so please use us!”

Jane Southam, public contributor

Can we embed public involvement in knowledge mobilisation throughout the research cycle?

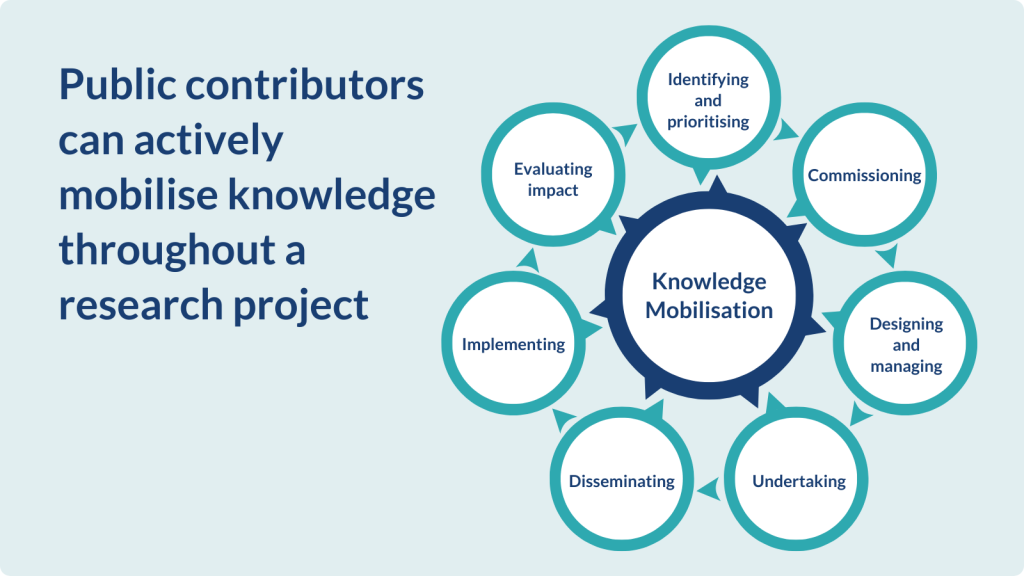

Research teams should plan knowledge mobilisation strategies from the beginning of the research project. Public contributors can actively mobilise knowledge throughout a research project. Their involvement creates opportunities for research teams to learn, to share and to shape knowledge to suit their research project.

What value can patients and the public add?

Working in partnership with local communities can ensure that research is relevant and meaningful. Devolving power to local people who represent their communities is an effective strategy for moving knowledge and facilitating change.

For example, a global health research programme was designed to improve health outcomes for people with a skin condition called cutaneous leishmaniasis. Community engagement and meaningful participation from local communities was instrumental in effectively mobilising research findings.

Local knowledge and settings were considered at the outset of study design to increase the relevance of research; community advisory groups were established in the three countries (Brazil, Ethiopia, and Sri Lanka) to co-produce knowledge. Co-approaches included activities using music, dance, and images to minimise power dynamics between researchers and research users. Local health workers, farming societies, women’s groups, and other stakeholders, played a central role in mobilising knowledge about the project among community members.

The researchers concluded that community members needed to have agency over the direction of the research, as well as to be involved in the mobilisation and implementation of research findings.

‘Using carefully considered facilitatory approaches, patients and the public can challenge both health and care professionals and the balance of power to contribute to decision-making in healthcare implementation’. School for Primary Care funded Research

Public contributors can bring a fresh perspective when co-designing outputs for sharing (e.g., evidence-based tools, new innovations, resources). For example, in an NIHR-funded Eczema Mindlines Study, researchers worked with a group of parents, carers and children to co-design and deliver knowledge mobilisation strategies to improve eczema self-care.

Five key messages about eczema treatment and self-care for children were co-created by the group. Easy-to-understand, attractive and accessible resources explaining these messages were co-designed for different audiences.

An animation, book, and teacher resource pack could spark conversations about the research and increase use of self-care advice by people with eczema, their parents, or teachers. An evaluation suggested that the co-created interventions had most impact when they:

- included simple consistent messaging

- were adapted to the audience

- took flexible approaches to knowledge brokering

- used personal networks and built relationships.

Another example of public and patient involvement in knowledge mobilisation came via the NIHR Impact Accelerator Award. The award was used to mobilise knowledge from public health research exploring safeguarding and the experiences of children and young people affected by parental substance misuse.

Creative workshops included activities such as free writing to music; the aim was to generate ideas for a book to facilitate conversations between trusted adults and children who had experienced parental alcohol or drug use.

The Twinkle Twinkle Arti book was co-developed with parents, children and teachers. It considered the main themes from the research (such as children and young people feeling alone in their experiences, with few people to talk to) and included quotes from young people. The authors are gathering feedback and plan to develop an animation.

Considering how to share findings as a research study progresses allows stakeholders to reflect and respond to their findings in a timely manner. It may help them identify additional opportunities to maximise the impact of research. Current NIHR-funded social care research is exploring the experiences of, and service provision for, people with dementia who live alone.

The research has embedded knowledge mobilisation and collaborative working from the outset. This includes integrative workshops involving researchers, a local service social care organisation, user-led organisations, and dementia networks.

Other knowledge mobilisation strategies used in research on employment for people with developmental disabilities include workshops, webinars and current affairs panels (attended by members of the public) to share relevant co-produced policy knowledge.

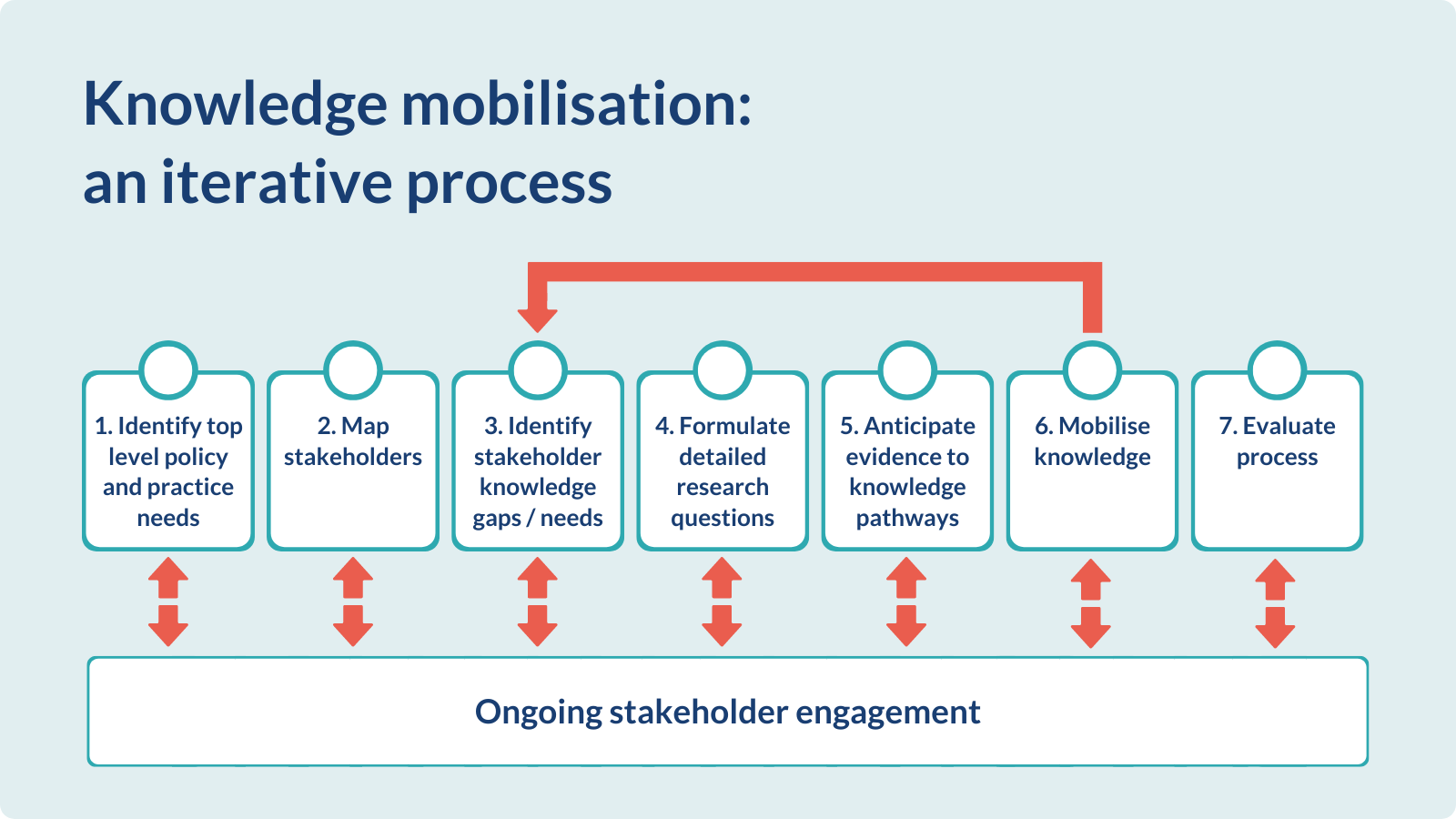

Iterative process in knowledge mobilisation; stakeholders remain engaged and feedback learning which guides research (adapted from ‘Supporting Knowledge Mobilisation within the NIHR HPRUs: Learning from the first year’)

Studies have shown that engagement with, and mobilisation of, research knowledge is more effective when information is delivered by a source perceived to be competent, authoritative, visible, and trusted. NIHR-funded studies on COVID-19 (specifically on vaccine hesitancy, developing messages for ethnic minority communities and tailored vaccine interventions) demonstrated the benefit of harnessing the experience and knowledge of members of the public (faith groups and community leaders); key people could mobilise knowledge and address potential barriers to implementation.

For example, one study explored how best to increase COVID-19 vaccine uptake among ethnic minority groups. It found more mistrust of the research and health advice about vaccinations when information was delivered by scientists and politicians (compared to local community leaders).

Researchers worked with public members of ethnic communities to understand how to shape the key health messages, identify trusted communication channels and how best to mobilise knowledge at the start of the research. They were supported by regional ethnic community groups, knowledge champions (community and faith leaders), knowledge advocates from public health, and health professionals. With this backing, the researchers shared their finding via a short YouTube film and electronic leaflet that could be viewed on a smartphone.

Training local messengers and role models as community champions to deliver consistent, relevant messages, facilitate dialogue and bust myths, may effectively change behaviour.

Members of the public (friends, work colleagues, faith leaders, families, neighbours) can mobilise knowledge within communities. They are informed and trusted representatives of their community, and have access to networks that researchers often lack. These credible intermediaries can mobilise knowledge across boundaries.

Public champions or knowledge champions can engage their networks to improve connections between researchers, organisations and underserved communities, share appropriate public health and social care messages, and facilitate implementation. By bringing together people with a range of perspectives and types of knowledge, research evidence can be made accessible, and understandable; this can support its translation into usable information tailored to local contexts and cultures. In this way, research evidence can be applied to ‘real-world’ challenges in local settings to drive change.

Public contributors benefit from understanding the context and background of research that they have been involved with; they may feel a sense of ownership in the mobilisation of findings. They often passionately want to see action as a result, and they may want to take key messages from the research to their community.

The ultimate aim of involving members of the public in knowledge mobilisation is to facilitate implementation of research and drive change in policy and/or practice. Co-approaches can help develop reciprocal relationships and build trust between all stakeholders; so that members of the public feel equal, empowered, and safe to respectfully challenge ideas.

Creative approaches to knowledge mobilisation include theatre, which can bring research findings to life. Theatre can clearly show the perspectives of diverse communities, prompt debate and shape research findings into actionable outputs. Forum theatre can create meaningful dialogue between patients, practitioners, and researchers, and has led to enhanced NHS care.

For example, in a study on post-injury psychological interventions, forum theatre enhanced individuals’ knowledge, confidence in knowledge and mutual understanding. This led to changes in behaviour, practice and research.

Other research explored the experiences of vulnerable people and the advice and support given in an area where Universal Credit had been rolled out. These experiences, along with the lived experience of people and frontline staff, informed the development of a film to share the findings with policy makers.

Other examples of co-approaches include design (collective making), and the use of board games and illustrations.

A research project illustrated some of the roles undertaken by patients and carers in implementation across four service pathways in two NHS Trusts. They included sharing experiences, identifying improvement priorities, generating innovative ideas and solutions to local service problems, and helping to implement and evaluate solutions through ongoing engagement and co-working with the Trusts.

Practical advice for researchers

Commonly-reported challenges to involving members of the public in knowledge mobilisation need to be overcome. We need to involve people with representative views, and find appropriate ways to communicate and engage them. But these activities cost time and money; we need to recognise the need for sufficient resources to fund public involvement in knowledge mobilisation.

So how can we increase the involvement of members of the public in knowledge mobilisation? Here are some top tips and resources to get started.

Funders and researchers need to be flexible and share power with public contributors when designing and conducting research and when making decisions. Co-approaches can build meaningful partnerships, trust and reciprocal relationships throughout the research cycle.

Reflection and two-way learning (where researchers are willing to change their approach in response to feedback) are important for working in partnership.

Members of the public can also contribute to research and support knowledge mobilisation as peer researchers. Peer researchers facilitate data collection and interpretation as they have trusted relationships with study participants.

They can actively support the use of research evidence among their networks by championing the findings, helping to develop suitable communication strategies and acting as intermediaries between stakeholders.

The Citizen Science approach in the RAPID and Efficient Eczema Trials (RAPID programme) is used to co-produce techniques using consistent messages in varied formats; the aim is to accelerate knowledge mobilisation of the emerging evidence. This collaboration with members of the public can make research more relevant, accessible and inclusive, and is likely to improve uptake of the findings.

Many of the principles established in public involvement in research, can be applied to knowledge mobilisation. The UK Standards for Public Involvement describes good public involvement and provides examples of best practice. Its overarching aim is to improve public involvement practice.

Specific guiding principles for embedding public contribution in knowledge mobilisation and implementation are available along with practical resources such as this Knowledge Mobilisation Toolkit and these knowledge sharing principles. Other toolkits can be found here.

Identifying appropriate public contributors for knowledge mobilisation activities is multifaceted. Researchers need to understand their skills, roles in society, public connections, networks, and links (with groups and charities for example) and how these assets can contribute to knowledge mobilisation.

Public contributors need to fully represent the target audience. Since many knowledge mobilisation activities are creative, people do not necessarily need to read English to be included. Building relationships and undertaking activities can be time-consuming and demanding.

The NIHR has produced guidance and support for involving members of the public in research activities, including under-served groups in health and care research and on promoting inclusion in public partnerships.

Members of the public involved in knowledge mobilisation require dedicated, tailored support. Research exploring knowledge mobilisation in Communities of Practice stressed the need to clarify their roles and expectations.

Involvement in knowledge mobilisation and implementation requires specific skills; public contributors may need support and training to understand knowledge mobilisation language, and their role within a project or group.

The Link Group at Keele University is an example of a dedicated patient and public group for knowledge mobilisation. The group was initially funded by an NIHR Knowledge Mobilisation Research Fellowship and has developed a supportive infrastructure and dedicated resources to empower public contributors to contribute and lead knowledge mobilisation activities.

Public involvement in knowledge mobilisation requires sufficient resources. Activities need to be planned at the outset of research with appropriate resources allocated. However, it is never too late to include members of the public in knowledge mobilisation even after the project has started.

The NIHR is promoting knowledge mobilisation strategies that include public involvement throughout all research projects; it recognises that these activities require resources.

Opportunities for funding encourage researchers to involve members of the public in the development of collaborative knowledge mobilisation strategies. NIHR awards that support and promote knowledge mobilisation include the Research Programme for Social Care, Advanced Fellowships, Development and Skills Enhancement Award, the School for Public Health Impact Accelerator Awards, and Programme Development Grant – Developing Innovative, Inclusive and Diverse Public Partnerships. Further support for researchers can be found here.

Ongoing NIHR work

Involvement of members of the public in knowledge mobilisation and implementation is in its infancy. Greater understanding is needed on how best to do this throughout the research cycle, and what impact public involvement has. As Sophie Staniseweska, Professor of Health Research, University of Warwick, observed in a recent NIHR webinar.

“At the moment, a lot of the knowledge that guides what we do is very much held in practice. Until evidence and theory are developed, then practice knowledge is our primary source”.

Sophie Staniszewska

Ongoing work funded by the NIHR will help to address this gap. For example, the ‘Pathways to Implementation for Public Engagement in Research’ (PIPER) study, is exploring the role of patients and the public in implementing health and social care research in practice. The study aims to answer questions about how the public can be involved in implementation, including:

- how can they help get research evidence into practice?

- what roles might they have?

- how can they best be supported?

The study will co-produce knowledge and a toolkit of resources to help research teams work in partnership with patients and the public in implementation activities.

Conclusion

This Collection explores public involvement in knowledge mobilisation. Planning and embedding public involvement activities from the start of a research project, can ensure that research evidence is relevant, timely and used by stakeholders. Members of the public use research, and can act as trusted intermediaries; they can drive the mobilisation of findings to relevant groups to inform decision making and facilitate change.

Evidence about public involvement in knowledge mobilisation is in its infancy. But practice-based examples, such as those highlighted in this Collection, can inform knowledge mobilisation plans. Designing studies to explore the role of public contributors in knowledge mobilisation activities throughout the research cycle could provide evidence to maximise their potential to drive change.

Researchers have a responsibility to work with patients and the public to empower them to contribute to and lead knowledge mobilisation activities. In turn, patients and the public can become champions of their own evidence-based health and care-related knowledge.

Author: Laura Swaithes, Knowledge Mobilisation Research Fellow at the NIHR

How to cite this Collection: How to involve the public in knowledge mobilisation: insights from the NIHR; March 2024; doi: 10.3310/nihrevidence_62360

Disclaimer: This Collection is not a substitute for professional healthcare advice. Please note that views expressed are those of the author(s) and reviewer(s) at the time of publication. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

NIHR Evidence is covered by the creative commons, CC-BY licence. Written content and infographics may be freely reproduced provided that suitable acknowledgement is made. Note, this licence excludes comments and images made by third parties, audiovisual content, and linked content on other websites.