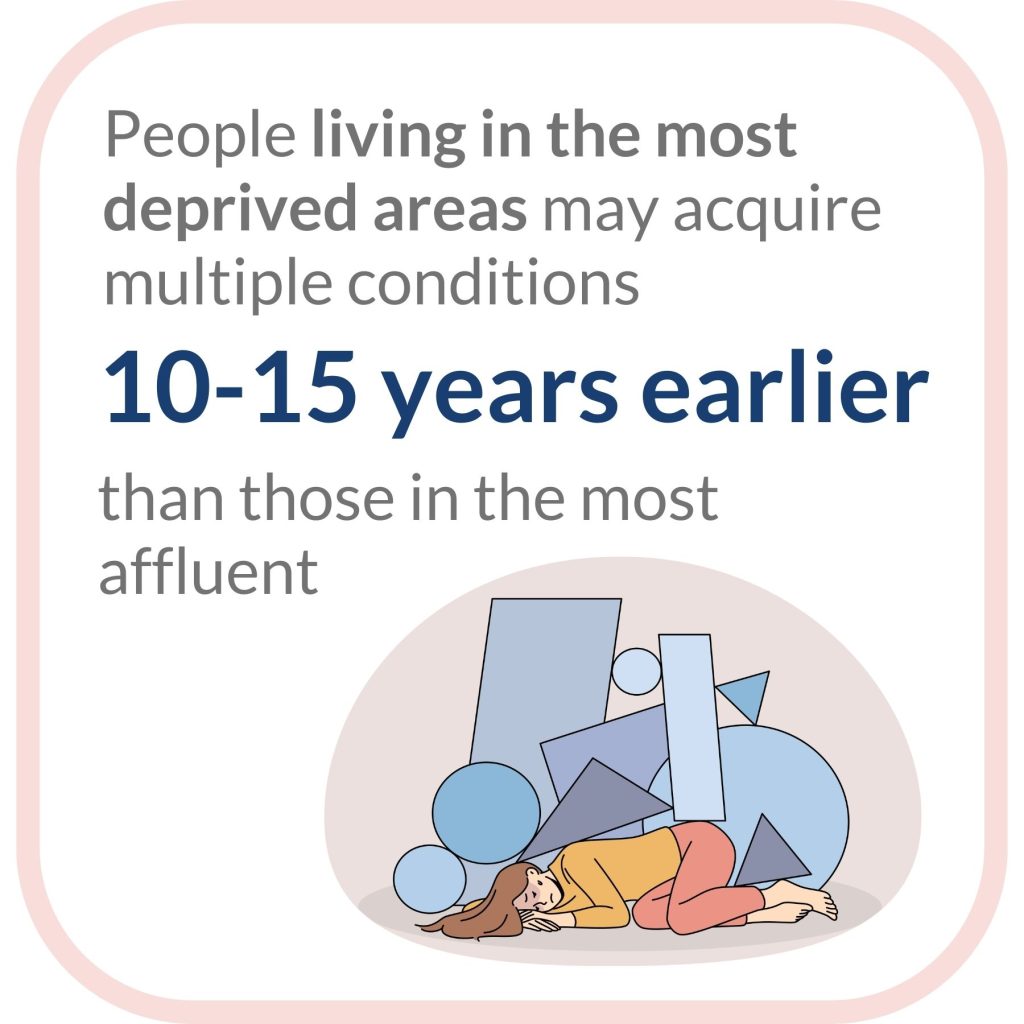

In England, there is a 19-year gap in healthy life expectancy ….between the most and least affluent areas of the country, with people in the most deprived neighbourhoods, certain ethnic minority and inclusion health groups getting multiple long-term health conditions 10 to 15 years earlier than the least deprived communities, spending more years in ill health and dying sooner.

(Health disparities and health inequalities: applying All Our Health, Office for Health Improvement & Disparities, 2022)

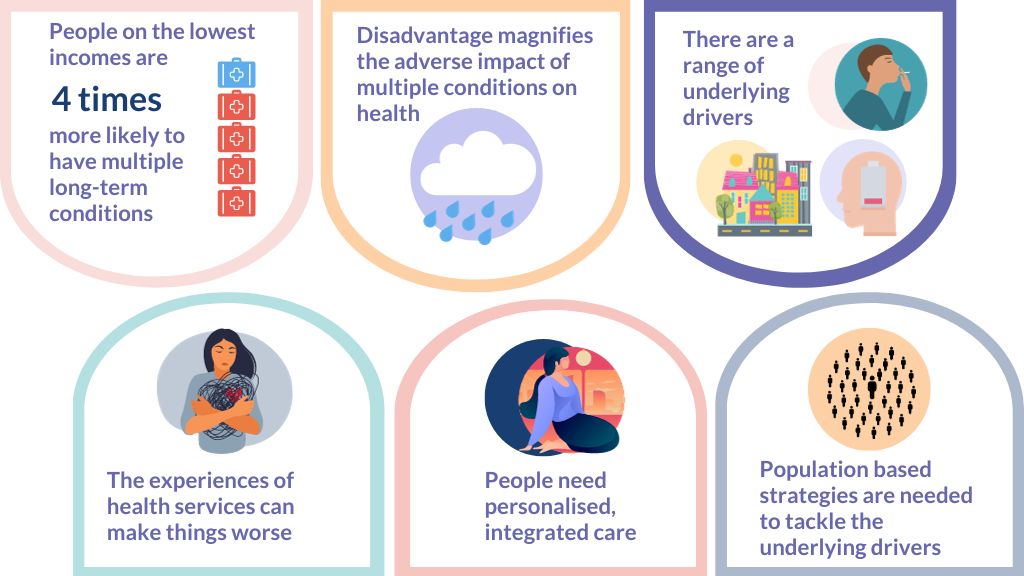

Two pressing and interconnected public health challenges are the rising number of people living with multiple conditions, and inequalities in health.

This Collection explores the intersection of the two: how discrimination and disadvantage increase the likelihood of multiple conditions, what drives the variation between different groups of people, the implications for health, and how services can help.

The research highlighted in this Collection will interest those who design and deliver health and care services, especially in areas of deprivation.

Key messages

- The groups at greatest risk include people from disadvantaged backgrounds, minority ethnic groups, and those with serious mental illness. For example, people with the lowest incomes can be four times more likely to have multiple conditions than those with the highest incomes.

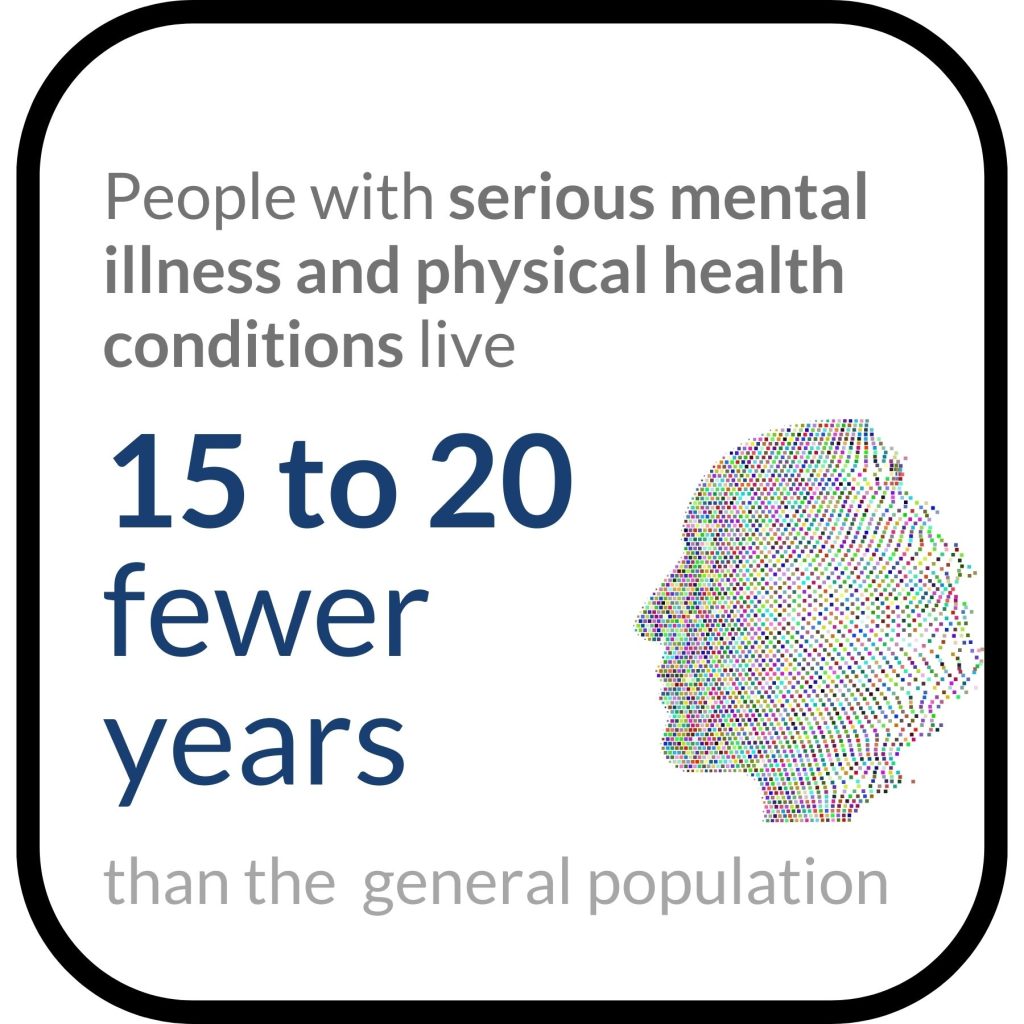

- The impact on health is cumulative. Multiple conditions and deprivation both have an adverse impact on life expectancy and disability-free life expectancy. For example, the most affluent women without multiple conditions can expect nearly 8 more disability-free years of life than the least affluent with multiple conditions. People with serious mental illness and physical health conditions live 15 to 20 years less than the general population.

- Underlying drivers may include health-related behaviours, access to material resources, and the psychological response to social inequality. It is likely that many factors reinforce each other, but evidence about key causal pathways is limited.

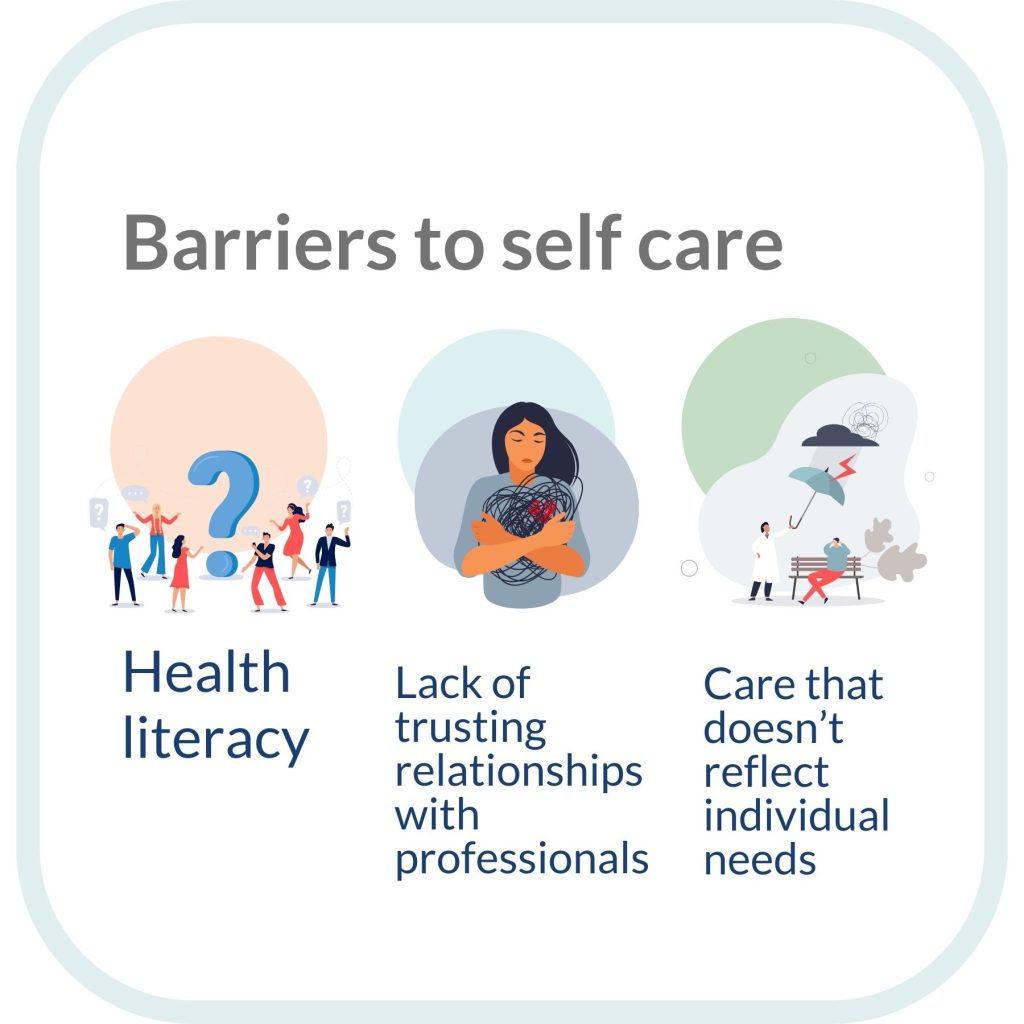

- Experiences of health services differ. The particular needs of disadvantaged groups are often neglected or even made worse by services’ responses. They are more likely to face barriers to self-care. These include poor health literacy, a lack of trusting relationships with professionals, and care that does not reflect their individual needs.

- Effective support could be delivered by services structured to deliver care for the whole person, rather than for single conditions. Services need to be tailored to meet the needs of local communities, especially those facing the greatest disadvantage. Bespoke support can help people adopt healthy lifestyles, understand and manage their conditions and reduce inappropriate prescriptions. Professionals need the resources and time to deliver personalised care.

- Population-based strategies are needed alongside service-level changes to tackle the environmental, social and economic determinants of health.

Introduction

Health inequalities and multiple conditions are both strategic priorities for the Government and the NIHR. The NHS’ Core20PLUS5 initiative aims to reduce healthcare inequalities at both national and system level. Core20 refers to the most deprived 20% of the population. PLUS groups, defined locally, are likely to include people with multiple long-term conditions. The Core20PLUS5 initiative aims to accelerate improvements for these groups.

In 2021, NIHR Evidence produced a high level summary of recent research on living with multiple conditions.

- The number of people with multiple conditions is rising. Living with numerous and often complex health problems is becoming the norm for older people and those from disadvantaged communities.

- People with multiple conditions are more likely to have poorer health, poorer quality of life and a higher risk of dying than those in the general population. Some combinations of mental and physical diseases are associated with especially poor outcomes.

- People with multiple conditions frequently share common problems. They may have reduced mobility, chronic pain, shrinking social networks, incapacity to engage with work, and lower mental wellbeing. To date, these problems have not been well-addressed by services or research. People with multiple conditions want greater service integration, more person-centred, holistic care, and better support for mental wellbeing.

- The healthcare system tends to focus on individual diseases or issues. It frequently fails to respond to the needs of the whole person. The evidence on the effective management of multiple long-term conditions remains sparse.

- An area of particular importance is the interface between physical and mental health. The two are closely interconnected. Each can adversely impact the other through a number of pathways, with consequences for health and wellbeing.

- Multiple conditions drive increased healthcare costs and the use of hospital and primary care.

- A common consequence of multiple health conditions is receiving numerous medications for long periods. This phenomenon, known as polypharmacy, is associated with adverse health outcomes.

- Biological, psychological, behavioural, socioeconomic and environmental factors are associated with a higher risk of developing multiple conditions. Deprivation is particularly important, alongside obesity, poor diet, smoking, air pollution and alcohol. In addition, some medications used over time magnify the risk of acquiring another condition, and some diseases increase the risk of others.

- Biological mechanisms and pathways at the cellular level may trigger other conditions, even when the co-occurring conditions appear unrelated. There are also higher rates of multiple conditions in older people, women and those from some ethnic groups.

- How biological, psychological, behavioural, socioeconomic and environmental risk factors interact to trigger multiple conditions is complex and not fully understood. More research is needed to understand how risk factors interact to produce one and then clusters of conditions, both in the general population and in specified population subgroups.

- Evidence on the best approaches to prevent multiple conditions is generally lacking. The importance of deprivation and other common public health risk factors means that effective prevention is likely to require population-based strategies that tackle the environmental, social and economic determinants of health.

Since then, more studies have looked at the twin issues of multiple conditions and health inequalities. We are therefore able to explore this important intersection in more depth.

This Collection draws on recent research on multiple conditions (multimorbidity) and health inequalities funded by NIHR. It was augmented through wider literature searches. The studies included are primarily analyses of large data sets, or systematic and other reviews of evidence.

Which groups of people are at greatest risk of both multiple conditions and health inequalities?

Deprivation

Multiple studies have found associations between multiple conditions and deprivation. People with the lowest incomes can be four times more likely to have multiple conditions than those with the highest incomes. But patterns of disease vary. For example, a systematic review found women were more likely to have musculoskeletal problems, while cardiovascular problems were more common in men. People living in the most deprived areas may acquire multiple conditions (two or more) 10–15 years earlier than those in the most affluent. They are also more likely to have mental ill health as one of their multiple conditions. A more recent study found that, in the most deprived areas, people acquired three or more conditions (complex multimorbidity) when they were 7 years younger, compared with the least deprived. The study found that inequalities in all but the oldest age groups have increased over time.

Ethnicity

Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Black African, Black Caribbean people, and those who identify as Black other, other Asian, and mixed, are at significantly increased risk of having multiple conditions (after adjusting for age and sex). People from the Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities are more than twice as likely to have multiple conditions as Chinese groups. They also have significantly higher rates of diabetes, chronic pain and cardiovascular disease.

Severe mental illness

People with severe mental illness are more likely to have multiple physical health conditions than the general population. This is particularly true for young people with severe mental illness. Those aged 15 to 34 years are 5 times more likely to have 3 or more physical health conditions.

Sexual orientation

Adults from sexual minority groups are more likely than others to have long-term mental and physical conditions, according to analysis of GP patient survey data, which adjusted for deprivation, ethnic group, region, and age. Young sexual minority adults, especially women, were much more likely to be living with multimorbidity.

What is the impact on health?

The risk of dying for people with multiple conditions who live in the most deprived areas is significantly greater than for those in the least deprived areas. The risk of dying associated with multiple conditions is also significantly higher for Pakistani, Black African, Black Caribbean and other black ethnic groups compared with White ethnic groups.

Data from large population-based studies demonstrates the cumulative impact of both multiple conditions and economic deprivation on life expectancy and disability-free life expectancy. For example, consider disability-free life expectancy among women. The most affluent can expect 3 years’ more disability-free life than the least affluent. Among the most affluent women, those without multiple conditions can expect 6 years’ more than those with multiple conditions. And the most affluent women without multiple conditions can expect nearly 8 years more than the least affluent with multiple conditions. This research found a widening inequality gap between the most and least affluent over time.

The impact is greatest for people with serious mental illness and physical health conditions. On average, their lives are 15 to 20 years shorter than for the general population, mostly because of preventable physical illnesses.

What are the underlying drivers?

Socioeconomic disadvantage

The wealth of evidence described, highlights the association between socioeconomic inequalities and multiple conditions. There is also evidence for associations between multiple conditions and factors linked to socioeconomic disadvantage: low educational attainment, living in a deprived area and unhealthy lifestyles. A systematic review found that household-level differences, such as home ownership and who was living in the household, were under-explored. As was the interplay between these factors and demographic factors such as age, gender and ethnicity. A study found a strong association between food insecurity and an increased risk of multiple conditions.

Underlying mechanisms

Clear evidence about underlying causal mechanisms is scarce. A review of 64 studies found that mechanisms were hypothesised, but rarely tested.

Potential mechanisms to explain the link between inequality and multiple conditions include:

- health-related behaviours such as diet, smoking or alcohol consumption

- access to material resources such as finance and housing.

- psychological response to social inequality such as living in a sustained state of stress.

The authors note the lack of evidence to support these pathways (behavioural, material and psychosocial). More evidence would help policymakers identify effective interventions, they say.

Researchers have also argued that better understanding of clusters of multiple conditions could help identify the underlying pathways.

Factors reinforcing each other

In reality many of these factors intersect and reinforce each other. A systematic review of ethnic inequalities in multiple conditions hypothesised:

“It is possible that racism and multiple forms of discrimination can intersect with demographic factors (e.g. age, gender, and/or sexual orientation) resulting in disadvantage in accessing key economic, physical and social resources for some, thereby, leading to socioeconomic and health inequalities. In turn, these inequalities can result in higher prevalence of some health conditions which may then accelerate the development of MLTCs in some minoritised ethnic group populations.”

Evidence on the association between depression and multiple conditions suggests that these two factors may drive and reinforce each other. A variety of common underlying mechanisms could include low socioeconomic status and psychosocial stress.

Ethnographic research from the Richmond Group of charities looked at the experience of 32 people with multiple conditions experiencing health inequity and disadvantage. Factors at play included the type of work they did, including their working patterns and hours.

"I would leave home for work at 5am and come back after 11pm, then do the house chores. So I’d just drink coke and eat cake throughout the day. It was quick to eat and gave me energy. " - Vera - a retired cleaner

The area they lived in, the quality of their environment and access to services all had an impact. Their financial circumstances had implications for their lifestyle. The other people they interacted with, and their underlying beliefs about the world around them, played a role. Many had developed unhealthy habits, such as a poor diet and lack of exercise, which were hard to break.

"It's hard to educate a 30-year-old about healthy eating when they've been eating microwaveable food their whole life" -Community centre manager, Middlesbrough

How do experiences of health services differ?

People with multiple conditions need effective support to manage their conditions. Our previous review found that the health and care system frequently fails to respond to the needs of the whole person, and instead focuses on individual diseases or issues. This means they often fail to see what matters to individual people. Their mental health needs and emotional wellbeing are frequently ignored, which can exacerbate their problems. The fragmented nature of care makes it difficult to navigate services.

A systematic review of international studies (by Woodward and others) explored issues faced by people from deprived communities in managing their multiple conditions. Researchers identified a constellation of interrelated issues, which created barriers to effective self-management. These included financial barriers, health literacy and the combination of multiple conditions and deprivation. Managing multiple medications was also an issue.

Lack of trust and personalised care

The ethnographic research by the Richmond Group also explored people with multiple conditions’ experience of health services. This research highlighted challenges including: access to health services, understanding the care they were receiving; and knowing how to best manage their condition, particularly if English was not their first language. The research pointed to a lack of trust and of personalised support that is sensitive to individual needs.

"My mum takes a while to explain things and get to the point. I think this is why the GP doesn’t listen to her." - Rahmiya, Sabba’s daughter

Some people were not clear about the link between their behaviours and their health.

"I only recently learned that it’s not good for me. I wish someone had properly explained it to

me. In normal English." - Kumar, 40, Stockwell

A rapid evidence review by the NHS Race and Health Observatory identified ethnic inequalities in a range of service areas (not limited to people with multiple conditions). The authors found distrust of both primary care and mental health care providers, as well as a fear of being discriminated against in healthcare. This often deterred people from seeking help.

Poorer disease management

Another systematic review described the “sparse” evidence base on ethnic differences in healthcare use and quality for people with multiple conditions. There was evidence of poorer disease management for some ethnic groups. For example, Black people with multiple conditions were less likely to be prescribed statins, and to reach set blood pressure targets.

Less continuity of care

Analysis of nearly 400,000 GP patient records found that people from Bangladeshi, Pakistani, Black African, Black Caribbean, and any other Black background experienced less continuity of care than White patients. People from areas of deprivation, similarly, had less continuity of care. Those from ethnic minority groups in the areas of greatest deprivation experienced the least continuity of care. Continuity of care, the ongoing relationship between patient and GP, is associated with lower mortality, lower hospital admissions, fewer disease complications and higher patient satisfaction. It is particularly important for people with multiple conditions and complex care needs.

What could help?

The Richmond Group of charities’ ethnographic research aimed to help people facing inequity and disadvantage manage multiple conditions. The report recommended: designing and adapting local services to meet the needs of local communities; promoting healthy lifestyles and behaviours; helping people to take control of their health; local efforts to tackle the wider determinants of health. These themes are echoed in the research in this Collection.

Promoting a healthy lifestyle

Research featured on NIHR Evidence demonstrated that adopting healthy lifestyles can extend life expectancy by up to 7 years in people with multiple conditions. The greatest benefits came from not smoking and from regular exercise. The researchers acknowledged that adopting healthy lifestyles can be harder for people in deprived circumstances, and for those with mental illness. A smoking cessation intervention was developed specifically for people with severe mental illness.

Support for self-management

The systematic review by Woodward and others concluded that people experiencing both deprivation and multiple conditions need extra help to self-manage. Health professionals can help people understand how to look after their health and their conditions.

Small but powerful adjustments, like simple, clear explanations of what had been diagnosed and what they need to do about their condition, professionals checking their understanding of what they had been told and asking their opinions on what they wanted to happen, would make a huge difference.

Richmond Group

Integrated models of care including medicines management

Bennet et al argued that healthcare professionals, especially those in primary care with limited time, urgently need more support. They need systems which support the management of multiple rather than single conditions, and help to reduce the number of medications prescribed.

The challenge of managing multiple medications was cited repeatedly. A study featured on NIHR Evidence explored how to reduce the number of medications for people with multiple conditions. It identified factors that can help clinicians deprescribe.

- Clarity on how and when to prescribe outside of guidelines, and on their professional responsibilities when doing so

- Access to high-quality data about patients’ medication history, but also life stage and key events such as recent bereavement

- Discussing plans to stop a medicine when it is first prescribed to develop a shared understanding of the purpose of treatment

- A trusting relationship with patients.

Management of combined physical and mental health needs

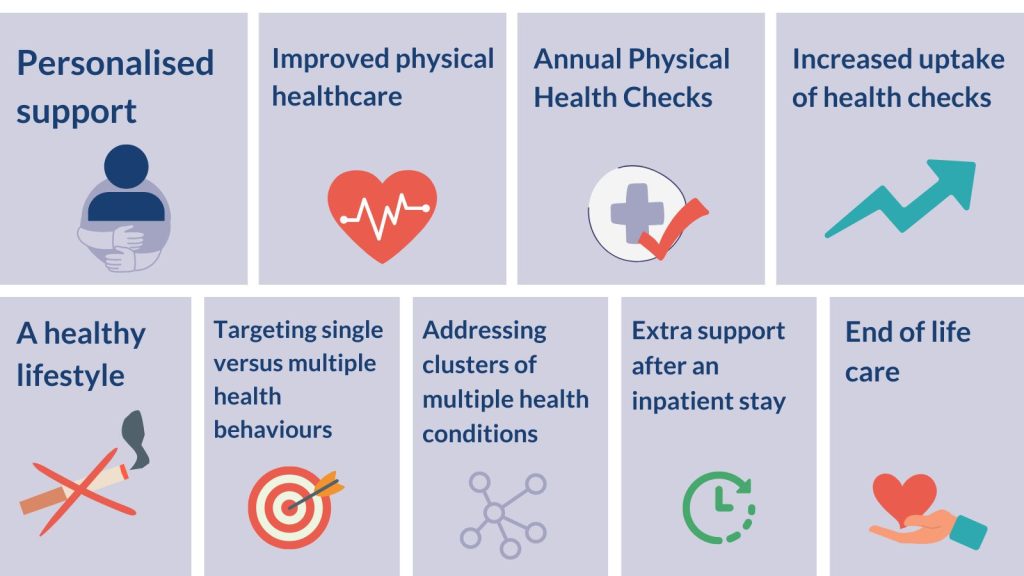

People with the combination of physical and mental conditions need extra help. The NIHR Evidence Collection Supporting the physical health of people with severe mental illness explores opportunities to do this (see figure below).

Addressing the wider determinants of health

Bennet et al argued that high-level strategies are needed for maximum impact. These include unpolluted outdoor spaces, better-paid employment with safe working conditions, and access to high quality neighbourhood services such as housing, public transport and schools. These upstream solutions could delay the onset of long-term conditions and reduce multiple conditions in deprived communities.

Conclusion

This review brings into sharp relief how disadvantage is magnified for those living with multiple conditions. The intersection of the two has a cumulative impact on disability-free and overall life expectancy. Lifestyles and other factors are known to drive both inequalities and multiple conditions, yet the causal pathways remain unclear. More longitudinal research is needed to explore these pathways in order to identify the most effective interventions.

The evidence continues to find that our health system is structured to manage single rather than multiple conditions. It also suggests that the needs of those experiencing the greatest health inequalities are too often neglected or even made worse by services’ response. This includes people from disadvantaged backgrounds, minority ethnic groups, and those with serious mental illness. The evidence demonstrates the importance of services tailored to the needs of their local communities, in particular the most disadvantaged groups. More bespoke support could help people adopt healthy lifestyles, understand and manage multiple conditions, and reduce their prescribed medications. Population-based strategies are needed alongside service-level changes, to tackle the environmental, social and economic determinants of health.

Addressing the challenge of multiple conditions is a strategic priority for the NIHR and other research funders, including the MRC and UKRI. All invest in this area and coordinate their efforts through a cross-funder multimorbidity research framework (2020). A recent additional investment of £25 million will support nine new Innovation hubs. There is a collective ambition to address many of the questions highlighted in this review.

Useful resources

| Resource | Author |

|---|---|

| Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management | NICE |

| Tackling inequalities in healthcare access, experience, and outcomes | NHS England |

| Person-Centred Care toolkit | RCGP |

| Multiple Long Term Conditions (Multimorbidity): Helpful resources | The Academy of Medical Sciences |

| The multiple conditions guidebook | The Richmond Group of Charities |

| All Our Health: personalised care and population health | Office for Health Improvement and Disparities |

| Ethnic inequalities in health and care among people with multiple conditions | Health Foundation |

Author: Candace Imison, Deputy Director of Dissemination and Knowledge Mobilisation at the NIHR

How to cite this Collection: NIHR Evidence; Multiple long-term conditions (multimorbidity) and inequality- addressing the challenge: insights from research; September 2023; doi: 10.3310/nihrevidence_59977

Disclaimer: This Collection is not a substitute for professional healthcare advice. Please note that views expressed are those of the author(s) and reviewer(s) at the time of publication. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

NIHR Evidence is covered by the creative commons, CC-BY licence. Written content and infographics may be freely reproduced provided that suitable acknowledgement is made. Note, this licence excludes comments and images made by third parties, audiovisual content, and linked content on other websites.