This is a plain English summary of an original research article. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and reviewer(s) at the time of publication.

Autistic people experience different types of listening difficulties in noisy environments, sometimes with severe consequences. Research found that background noises could be distracting, drown out other voices, and overwhelm people. These difficulties affected autistic people’s social life, career, and emotional wellbeing. The research team says that greater understanding of these listening problems could allow autistic people to participate more fully in conversations and everyday life.

This study interviewed 9 autistic people and found that all had listening difficulties. The loudness of background noises, and the number of people talking, affected their ability to listen, as did other sights, smells, thoughts, and feelings. Coping strategies included looking at people’s lips or moving to a quieter room. Interviewees said that lack of understanding of their listening difficulties (by the public and especially by health professionals) made life much harder.

This research is part of the wider project called Speech Perception by Autistic Adults in Complex Environments (SPAACE). A larger study is being carried out to see how common these listening problems are among autistic people.

More information about autism is available on the NHS website.

The issue: the impact of noisy environments on autistic people

About 1 in 67 people in the UK are autistic. Many find it hard to communicate and to understand what other people are thinking and feeling. Autism affects how people process sensory information (such as sight and sound), which can make everyday tasks more difficult.

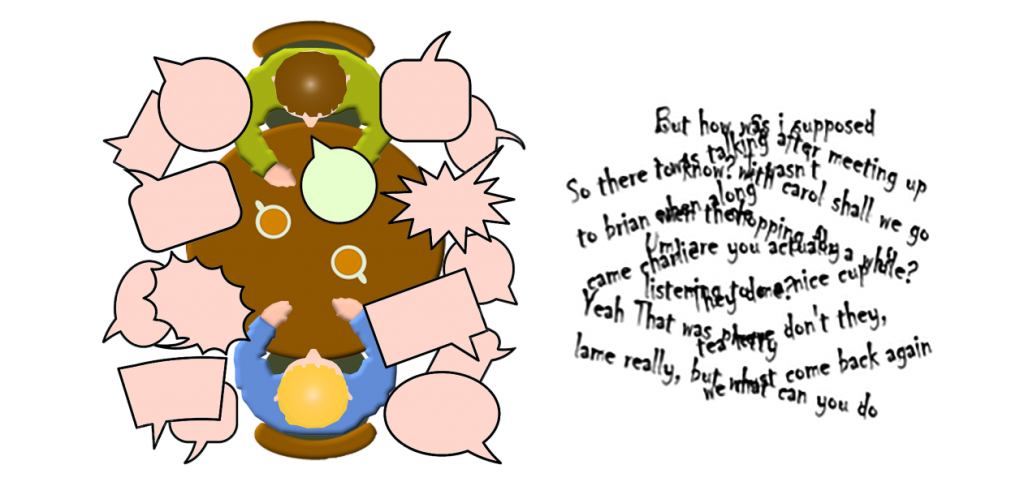

In a noisy environment, many autistic people say it is difficult to hear what’s being said. Background noises can create overwhelming listening difficulties. Conversations can become a jumble of words (as shown in the image below, created by the authors).

However, researchers have rarely asked autistic people about their personal experiences. In this study, researchers interviewed autistic people about their experiences of listening to speech. They explored their abilities and difficulties, how they were impacted by any difficulties, and what coping strategies they had developed.

What’s new?

Researchers interviewed 9 autistic people, aged 19 to 38 years. The 6-person study team included 2 autistic researchers, to reduce the risk of non-autistic people misinterpreting the experiences of autistic people.

Several common points emerged in the interviews.

- Background noise caused problems with distraction, drowning out or jumbling voices, and knowing where sounds were coming from. One interviewee said: "It doesn’t matter how loud that noise is, it will take me out of the conversation completely.” Lots of noise could also be distressing. Some autistic people could hear faint sounds others can’t; this could be a problem as well as a skill.

- Sensory overload. Some people struggled to listen if many conversations were going on; others were even more sensitive: “Even a group of just two people is so much more difficult than just one. It’s strange because… I like having all my friends there, but I don’t like even three-person conversations.” Being able to lipread was helpful, but information from other senses (sights, smells, pain) could cause problems. One interviewee said: “I was trying to listen … and someone near me … had this really strong like perfume or something … it was so distracting.”

- Social difficulties combined with listening difficulties could make life even harder. Some interviewees hid their listening difficulties, but this could lead to anxiety and isolation. People worried that their mishearing or withdrawal from conversations could be seen as rudeness. Autistic people were often frustrated that others, especially clinicians, did not understand their difficulties. One said: “You’re told again and again, ’No, no there’s nothing wrong’ and you’re trying to work out, ‘Then why can’t I hear someone? Why can’t I have a normal conversation?’”

- Listening difficulties could disrupt social and emotional wellbeing along with people’s education, self-image, and career. One interviewee had a job in a noisy call centre: “I was terrified of going to work. I’d be almost vomiting in the street, walking to work like ‘OK, I just can’t do this.’” Interviewees wanted to socialise, but straining to listen left them feeling drained: “Holding a conversation in the pub feels like work.”

- Coping strategies. Interviewees learned to look at people’s lips, move to a quieter room, or use high-fidelity ear plugs. Some participants used subtitles on TV, or completed their university courses online from the quiet of their own homes. Recognising their own listening difficulties allowed them to ask for help, but the process of finding help was difficult. People generally had to figure out their own coping strategies; they thought that clinicians should provide more guidance.

Why is this important?

In this study, autistic people described their difficulties in listening to speech. A lack of awareness of their difficulties by friends, family, organisations, and even clinicians, added to the burden.

The researchers hope their study will allow autistic people who have listening difficulties to better understand them, and to ask for help. It could also help non-autistic people, and clinicians in particular, to recognise listening difficulties and make accommodations for them.

The study also showed that fully involving autistic people in research is possible and adds real value. For example, autistic researchers ensured that the meaning of questions was explicit so that interviewees did not misunderstand. They also ensured that non-autistic researchers did not misinterpret autistic people’s responses during analysis.

What’s next?

The study was small, with just 9 autistic interviewees, who struggled to listen in noisy environments. It was advertised online, and may have excluded people with learning difficulties or a lack of access to the internet. The authors are conducting a larger follow-up study to see if the findings are the same in a larger population. Further research is also needed to investigate the causes of listening difficulties, using large numbers of people in order to understand the different types of difficulty.

The authors are creating a list of coping mechanisms for dealing with listening difficulties (supplied by autistic people), which they will share with the autistic community.

You may be interested to read

This summary is based on: Guest H, and others. Chasing the conversation: Autistic experiences of speech perception. Autism & Developmental Language Impairments 2022;7:1–12

Guidance from National Autism Resources that provides advice on helping autistic children with listening difficulties.

A news article about listening differences in autistic people.

Research article about the advantages of autistic people’s sensitivity to sound: Remington A and Fairnie J. A sound advantage: Increased auditory capacity in autism. Cognition 2017;166:459–465

Funding: This study was supported by the NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre.

Conflicts of Interest: The study authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer: Summaries on NIHR Evidence are not a substitute for professional medical advice. They provide information about research which is funded or supported by the NIHR. Please note that the views expressed are those of the author(s) and reviewer(s) at the time of publication. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

NIHR Evidence is covered by the creative commons, CC-BY licence. Written content and infographics may be freely reproduced provided that suitable acknowledgement is made. Note, this licence excludes comments and images made by third parties, audiovisual content, and linked content on other websites.