“Our care was so excellent and well-thought-out (taking photos, which seemed a bad idea at first but are now priceless treasures, for example), that we realised we were benefiting from many other parents’ grief.”

Listening to Parents Report, 2014.

Key messages

- Maternity care aims to be safe, effective and responsive at all times. For the great majority, pregnancy and childbirth is a positive and happy experience that culminates in a healthy mother and baby. But on the rare occasions when things go wrong, the effects are life changing.

- The rates of stillbirth and neonatal deaths have fallen by around 20% since 2010. However, recent years have also seen a decline in other indicators of safety and quality and notable failings in some hospitals. Outcomes for black and Asian women and those from more deprived areas in the UK were significantly worse.

- As the recent NHS England Three Year Delivery plan (2023) for maternity and neonatal services points out, some families have experienced unacceptable care, trauma, and loss, and have challenged the NHS to improve.

- This NIHR Collection highlights evidence from NIHR-funded studies and other important research, to support improvement in four areas that are critical to high quality maternity care. They are:

- Kind and compassionate care

- Teamwork with common purpose

- Identifying poor performance

- Organisational oversight and response to challenge.

- Evidence points to the need for:

- an open, compassionate, and learning culture to be promoted by hospital boards and clinical leaders across their organisation and within clinical teams

- team development to be enabled so that team members understand the team’s objectives and each other’s roles and competencies

- women to be empowered to be involved in decisions about their care through effective communication and information sharing

- high-quality bereavement care that is compassionate and sensitive to the needs of individual families

- staff training to include cultural awareness and team-based learning

- continuity of care to be prioritised in the organisation of care so that women have a named midwife

- strong clinical and quality governance; learning from and taking action on clinical and patient experience data including severe complications of pregnancy and deaths.

- The wider system needs to support these key areas, for example, by ensuring safe staffing levels and a high quality care environment.

Introduction

While the birth of a baby represents the happiest moment of many people’s lives, some families have experienced unacceptable care, trauma, and loss, and with incredible bravery have rightly challenged the NHS to improve.

Three year delivery plan for maternity and neonatal services, 2023.

The great majority of women will have a good childbirth experience and a safe birth. The rates of stillbirth and neonatal deaths have fallen by around 20% since 2010 according to the Office for National Statistics. However, recent years have also seen a decline in other indicators of safety and quality. Outcomes for black and Asian women, and those from more deprived areas in the UK, were significantly worse. Black women were 3.7 times more likely to die, and Asian women 1.8 more times likely to die, than white women, during or up to six weeks after pregnancy (Missing Voices MBRRACE Report, 2022).

The recent report into maternity services at East Kent Hospitals (2022) describes a series of care failings. Similar investigations resulted in the Morecambe Bay Report (2015) and Shrewsbury and Telford Report (2022). The Care Quality Commission 2022 survey also found a statistically significant downward trend on the majority of measures. The organisation said, “This reflects the increasing pressures on frontline staff as they continue in their efforts to provide high-quality maternity care with the resources available.”

The East Kent report identifies four areas for NHS action:

- Kind and compassionate care

- Teamwork with common purpose

- Capacity to identify poor performance

- Organisational oversight and response to challenge

In this NIHR Collection, we bring together recent research to help the NHS drive improvement in each of these areas. We have drawn primarily on research funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), but also on wider research and evidence-based guidance.

These areas closely align to the priorities set out in the recently published NHS England Three Year Delivery Plan. We hope this Collection will help Trusts in developing and implementing their plans.

For brevity, this Collection refers to all birthing people as women, regardless of their gender.

1. Kind and compassionate maternity care

“Compassionate care lies at the heart of clinical practice… Every interaction with a patient, mother and family must be based on kindness and respect.”

Reading the signals, Maternity and neonatal services in East Kent - the Report of an Independent Investigation, 2022.

Care that is kind and compassionate is at the core of maternity services. In an NIHR report on parents who had lost a child, one woman said “It was the worst experience of my life … with the best care… I’ll forever be grateful to the handful of women I’d never met before who got me through the birth and death of my son.”

Patient-focused care and shared decision-making

“We need to provide women with the resources and support to make informed decisions and train clinicians to have individualised care planning conversations, which uphold women's autonomy and meet their individual needs.”

Safer Maternity Care - The National Maternity Safety Strategy, 2017.

Effective communication, which involves women in decisions about their own care, builds their trust in maternity services. A good bedside manner can be as important as the medical care provided: “Although the medical care was excellent, we really felt that there was a lack of emotional support… I so desperately wanted and needed to talk to somebody… about what we were going through, and the decisions we had to make” (Listening to Parents Report, 2014). In the review of East Kent maternity services, one mother said care seemed like “something being done to you, and not something we were involved with.” The NHS’s move towards personalised and compassionate care depends on engaging people in decision-making about their own care.

Providing women with more information and resources empowers them to make decisions for themselves. For example, a study of women’s experiences of the induction of labour (when labour is started artificially) found that good-quality, appropriately-timed information helped women to be involved in treatment decisions. A previous NIHR Collection, Care and decision-making in pregnancy, highlighted the importance and challenges of good clinician-parent relationships in involving families in their treatment. However, a qualitative NIHR study on shared decision-making showed that midwives tended to do what they thought was clinically best, and did not routinely engage women in shared decision-making about their care during labour. Despite this, most women in the study were happy with their care, except when they had to ask for pain relief multiple times.

“It is not easy to balance benefits and risks, physical and psychological, for mothers and their babies, as well as for the NHS that bears the impact of treatments and complications.” Dimitrios Siassakos, Professor in Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University College London, NIHR Collection, Care and decision-making in pregnancy.

For example, NHS England’s Maternity Transformation Programme recommends that women should have a named midwife responsible for their care. This close relationship promotes trust and gives mothers control over the planning and provision of their care. Evidence suggests it can also save babies’ lives, prevent early birth, and improve women’s experiences and clinical outcomes.

Culturally-sensitive maternity care

“It means listening to people in our care. Respecting their choices as theirs to make… It means having a diverse staff body so that the culture changes from within… It means treating people like they are actually human, not just a skin colour.”

Systemic racism, not broken bodies report, 2022.

Women and babies from ethnic minority groups have worse outcomes than white people. There is an urgent need to improve care for people in these groups, and to rebuild their trust.

A report from the charity Birthrights found that women from ethnic minority groups were often not listened to, believed, or involved in decisions about their care. It also found that white bodies were seen as the norm, which meant that conditions such as jaundice could be missed in people with darker skin.

One of the report’s key recommendations was cultural awareness training to increase clinicians’ awareness of their own biases and how they impact care. For example, a national review of ethnic disparities in maternal deaths found that some clinicians thought black British women had a lower pain threshold than white women. Agitation in women who did not speak English was attributed to mental health problems, rather than distress when women were severely unwell. Improved understanding of different cultures would allow clinicians to appreciate women’s needs, and to provide personalised care.

Building trust in maternity services will require improved engagement with ethnic minority communities. This was a key recommendation from the Chief Midwifery Officer for England following reports that more pregnant women from ethnic minority groups were dying from COVID-19. She also recommended tailoring communications and health advice for these communities. A more diverse workforce, with more people from ethnic minority groups in senior positions, could help to address racial disparities in maternity care.

Bereavement care when a baby dies

“I felt like strangers around me became more like family. Their grief was obvious and a comfort to me. I felt like a person not their job.”

Listening to Parents Report, 2014.

Parents whose child has died have an intense need for kindness and compassion in maternity services and can benefit from high-quality bereavement care.

Early pregnancy loss, including miscarriage (before 24 weeks of pregnancy) and ectopic pregnancy (fertilised egg is implanted outside of the womb), can have a devastating impact on women. NIHR research found that almost 1 in 3 women who experience early pregnancy loss develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD, an anxiety disorder caused by distressing events).

Recent reviews of maternity services have highlighted the need to improve bereavement care, stating that “uncompassionate care can be devastating for… mental health.” Reading the signals, Maternity and neonatal services in East Kent - the Report of an Independent Investigation (2022).

The National Bereavement Care Pathway helps professionals support families to cope with different types of loss (such as miscarriage or the death of a newborn). The Evaluation of the National Bereavement Care Pathway (2019) found parents overwhelmingly agreed that they were treated with respect, communicated with sensitively, and that the hospital was a caring and supportive environment.

“Overall, the care we received cannot be faulted, and we are so grateful to have had this level of care. I truly hope this becomes a national standard that all bereaved parents will benefit from, as I cannot express how much it has helped us navigate through this most difficult time.” Parent of a stillborn baby, Evaluation of the National Bereavement Care Pathway.

Families are being supported by initiatives like this, along with resources from organisations such as Tommy’s, Sands, and the Miscarriage Association.

Mothers particularly valued a recommendation in the pathway to make memories with their critically ill child. For example, washing or clothing them. This finding was echoed in an NIHR study which examined the experiences of mothers whose newborn babies were dying. Women expressed their intense need for physical contact with their baby, which was sometimes difficult due to delicate skin or feeding tubes. The authors call for care that is responsive to the wishes of parents likely to lose their child.

For clinicians, one of the most challenging discussions they can have with parents is on whether to end life support for their critically ill newborn. Evidence-based training could help them guide women through this incredibly difficult decision. An NIHR study examined doctors’ style of communication during these conversations and found that parents presented with options rather than recommendations were better able to engage with their care. The authors suggest that giving parents options might help them deal with their bereavement in the long term.

Effective communication in bereavement care was also highlighted in an interview-based study of parents who had lost a baby. When people were told they were ‘losing a baby’ rather than ‘having a miscarriage’, they were more prepared for what was to come. For instance, the realities of labour and making decisions about seeing or holding their baby. This careful choice of words helped validate parents’ loss. As did opportunities to create memories of their child.

“David really appreciated encouragement from their midwife: ‘“Do you want me to take pictures? You will, appreciate these pictures. Not now, not tomorrow, but in the future.” And they're right.’” Parents’ experiences of care following the loss of a baby at the margins between miscarriage, stillbirth and neonatal death: a UK qualitative study (2020).

Support for fathers is often overlooked in bereavement care; most research has focused on the experiences of women. In an investigation into the experiences of parents who had lost a child, one mother said, “A father’s loss isn’t understood… it’s rather like primer applied to a wall, which eventually is painted over.” A recent study found that bereaved men sometimes felt excluded, isolated, and their grief invalidated (2020). Even witnessing a partner go through a traumatic birth can lead to some men experiencing depression or PTSD. Researchers from both studies recommended making support services for men more accessible, and validating their distress.

2. Teamwork in maternity care

Multiple clinical groups work together as a team to deliver safe maternity care. This includes obstetricians and midwives, along with a range of other medical specialists and allied health professionals. The importance of teamwork for safe maternity care is well understood, as outlined in the Safer Births Through Better Teamworking report (2015).

“Multi-professional working plays a vital role in the provision of high quality care for mothers and their babies.” Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and Royal College of Midwives joint statement on multidisciplinary working (2018).

However, the professional groups involved in maternity care may have different goals, values and cultures that can make working together difficult. The need to improve teamwork was identified as a major lesson in the East Kent review. The same observations were made in the Morecambe Bay and Shrewsbury and Telford Investigations.

“Failure to work effectively together leads directly to poor care and jeopardises patient safety. In maternity services, it leads to staff failing to escalate clinical concerns promptly or appropriately. As a result, necessary assessments and interventions are either done by the wrong people with the wrong skillsets or are not done at all. In both cases, the risks to safety are obvious.”

Reading the signals, Maternity and neonatal services in East Kent - the Report of an Independent Investigation, 2022.

In the most recent NHS staff survey (2022), only half of the respondents believed that teams within their organisation work well together. The survey considered factors known to contribute to good teamwork. Only half of the respondents felt that their team disagreements were dealt with constructively. One-third lacked a shared set of objectives for their team. Two-fifths said their team did not meet to discuss their effectiveness.

Effective teamwork in maternity care

A recent observation-based study of high performing maternity organisations (2020) echoed previous work on teams, highlighting the importance of teamwork and drawing out its key attributes.

There’s a really good relationship between the doctors and the midwives and as someone that’s new to this [hospital], I definitely felt very welcomed and I felt that the midwives were very keen to get to know me, to talk to me, to show me where things are… Everyone really cares for their women and is working towards helping them and achieving the best outcome. Registrar - Seven features of safety in maternity units: a framework based on multisite ethnography and stakeholder consultation (2020).

The attributes include team members understanding and valuing each other's roles, skills and competencies. When deciding who should perform a certain task, it suggested the team consider skills and experience as more important than seniority or professional roles, so that the person with the right skills for a specific task takes it on. This promotes teamwork and demonstrates collective competence. Staff support each other and have disruptive or bullying behaviours managed effectively. For example, open discussion and reference to shared goals can help to settle disagreements between professions or roles (on treatment decisions, for instance).

The East Kent report recommended that relevant medical and nursing professional bodies explore how team working in maternity and neonatal care can be improved. It made particular reference to establishing common purpose, objectives and training from the outset. A long-established principle, supported by the Royal College of Midwives, is that staff who work together should train together. A recent Cochrane review evaluated simulation‐based team training for obstetric emergencies (2020). It found that this type of training may improve team performance, and contribute to improvement of specific maternal and perinatal outcomes (compared with no training). However, high‐certainty evidence is lacking due to the serious risk of bias and imprecision, and the effect cannot be generalised for all outcomes.

A recent rapid review looked at interventions to improve teamwork in maternity services (2022). In general, the evidence for the interventions was variable and did not assess their long-term impact. There was little research around organisational and system-wide features that are known to impact on team working. For example, the impact of wider policy, organisational rewards and goals, resources allocated to general training and staffing. The following principles for effective interventions to improve maternity team working were suggested by the available evidence:

- provide opportunities for continuous and quality improvement at all levels - from front-line delivery to the organisation and wider system

- enable all team members to have a voice in improvement; encourage honest feedback

- allow comparison within and between teams (benchmarking)

- be adaptable; include different types of teams, such as those that manage safety/risk or work cross-boundaries

- build in managerial support

- use resources as efficiently as possible.

3. Identifying poor performance in maternity services

The East Kent report highlighted a lack of “useful information on the outcome of maternity services”. The Health and Social Care Select Committee report on maternity services recommended that:

“...the Department must assess current data gaps and develop a plan to address these. Particular focus should be given to using data to understand the causes of and reduce the variation between maternity units. National measures are driving improvements overall but there are some units being left behind. We need to know why.”

A wide variety of national and local data sources can be drawn on to monitor and identify poor performance. But the latest report, Better Births Four Year On: A review of progress (2020), from the NHS England Maternity Transformation Programme, acknowledges that data quality and timeliness remain problematic. A recent study, Worth the paper it’s written on? (2022), found 80% of Medical Certificates of Stillbirth in the UK contained errors; more than half (56%) had a major error that would alter its interpretation. Accurate recording of the cause of a stillbirth is important for families, and helps local and national learning. The authors recommend improved national surveillance processes alongside tools, guidance and training for those completing the certificates.

National reporting mechanisms for maternity care

Organisations can learn from a number of valuable national reporting mechanisms.

Maternal deaths

The United Kingdom’s Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths has been world-leading in its rigorous investigations and generation of learning at a national level. It has contributed to major improvements in the quality of maternity care and a reduction in the maternal mortality rate; maternal deaths are now rare.

Baby deaths

The MBRRACE-UK collaboration collects data on baby deaths in the UK. It analyses annually the numbers and rates of deaths. MBRRACE-UK has developed a tool to help organisations learn from each stillbirth and neonatal death, plus a real-time data monitoring tool reporting the number of deaths across trusts in the UK.

Care Quality Commission

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) national maternity survey identifies key learnings and areas for improvement in care in England. Learnings are also drawn out from the CQC Maternity Inspection Programme. From October 2023 the CQC will host the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch’s (HSIB’s) maternity programme. In 2018, HSIB (which was set up to look at factors that have harmed or may harm NHS patients in England) established a dedicated programme for maternity safety. The aim of the programme was to “bring a standardised, learning-oriented and person-centred approach to safety investigations that would produce insight to help reduce maternity safety incidents across the NHS.”

Local data on maternity care

Learning from severe complications of pregnancy

Maternal deaths are thankfully rare, but severe complications of pregnancy are more common. A major NIHR study analysed severe complications in order to generate evidence-based recommendations to improve care.

Patient Safety Incident Response Framework

The Patient Safety Incident Response Framework (PSIRF) sets out the NHS’s response to patient safety incidents, including maternity services. Its aim is to support improvement.

Patient safety incidents are unintended or unexpected events in healthcare (including omissions) that could have or did harm one or more patients. This framework encourages organisations to explore the factors that contributed to a patient safety incident or cluster of incidents.

Complaints data

The Francis Report into safety issues at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust stated that complaints could give insights into poor quality care. A recent realist review, Learning from complaints in healthcare (2020), explores how to respond to complaints in a way that meets patient needs. It also supports local and national quality improvement. The review recommends a systematic approach to analysing and learning from complaints. This includes:

- a reliable and meaningful coding system to classify complaints, for example, according to severity and the type of concern

- providing guidelines and training for the staff coding the complaints

- a centralised informatics system to capture and analyse the complaints data

- bringing together and comparing complaints data with other sources of patient feedback and incident reporting (triangulating).

Maximising the learning and improvement from performance data

As highlighted above, a systematic approach based on different sources of data can enable learning about performance. Better Births Four Years On: a review of progress also emphasised that data from multiple sources need to be brought together and compared (triangulated) to identify areas of poor performance. For example, the rate of caesarean sections alone is not a meaningful indicator of the quality of a service. A combination of performance data with patient and other types of feedback can help interpret the statistic.

In the National Perinatal Mortality Review Tool Report, MBRRACE-UK recommends that organisations invest more resources in undertaking and learning from local and national reviews. It found weaknesses in many of the action plans developed as a result of local reviews. This mirrors findings from the NIHR study into severe complications of pregnancy. The study found that local investigations varied in quality. It recommended safety checklists that trigger local action should capture both local and national issues of concern. An audit of recommendations from local reviews would help ensure that changes had led to the desired improvement in outcomes.

4. Organisational oversight and response to challenge

The East Kent and other investigations described the lack of effective action by hospital boards when presented with information that suggested quality issues.

“...the trust board did not have oversight or a full understanding of issues and concerns within the maternity service, resulting in neither strategic direction and effective change, nor the development of accountable implementation plans… This meant that consistently, throughout the review period, lessons were not learned, mistakes in care were repeated, and the safety of mothers and babies was unnecessarily compromised as a result.”

Ockenden Report, 2022.

A number of NIHR studies have explored the factors that contribute to good governance, as well as a culture of learning and quality improvement.

A major study of 15 healthcare organisations in England underlined the importance of boards’ active investment in quality improvement and culture of continuous improvement. The boards of healthcare organisations that had high-quality improvement capability and maturity:

- prioritised quality improvement

- combined a focus on short-term (external) priorities with long-term (internal) investment in quality improvement

- used data for quality improvement, not just assurance

- actively engaged staff and patients

- had a culture of continuous improvement.

A key feature was a focus on values that permeated every aspect of what they did and promoted a positive culture of trust.

"We’re very clear about it in recruitment processes, appointment processes, revalidation processes, and so on. Because trust is an essential ingredient." Interview, chair, Organisation 2 - How do hospital boards govern for quality improvement? A mixed methods study of 15 organisations in England (2017).

Clinical leaders had a particularly important role. Their in-depth knowledge and understanding of quality issues could provide the board with meaningful analyses of data. They could link ‘the board and the ward’; their involvement was a key factor in mature and high-quality improvement systems.

These factors closely mirror the findings of a King’s Fund report, which found that a healthy NHS culture was fundamental to high-quality care. A recent study by the Health Foundation on fostering continuous improvement in hospitals (2022) identified sustained commitment from trust leaders as important, as well as a culture of peer-learning and knowledge-sharing.

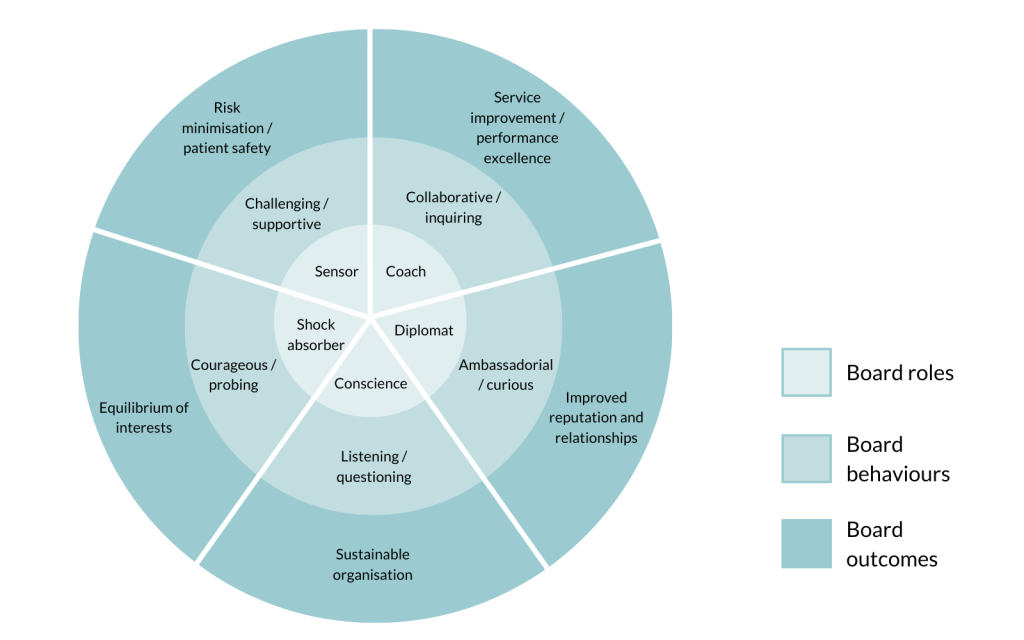

A recent mixed-methods study, Roles and behaviours of diligent and dynamic healthcare boards (2020), explored the behaviours of effective hospital boards. The review identified five key roles (see figure 1):

- Conscience of the organisation - setting and reinforcing values

- Shock-absorber - helping determine local priorities in a complex policy and regulatory environment

- Diplomat - managing relationships across the local health economy

- Sensor - scrutinising organisational performance to drive improvement

- Coach - setting direction while providing support to staff.

The study argues that effective boards successfully take on all of these roles. This resonates with the findings from the East Kent and other investigations, in which the boards demonstrated weaknesses particularly in the roles of conscience, sensor, and coach.

Along with engaging boards in quality improvement initiatives, women and families also need to take part; ultimately, they are the ones who will be affected by new policies. However, engaging people in the process can be difficult, particularly investigations of serious incidents, in which hospitals try to learn from their mistakes. Investigations often rely on reports from clinicians, and overlook the insights patients and families can offer. A study found that most people valued being involved in investigations of serious incidents, but conversations had to be handled sensitively. The researchers recommend that clinicians listen to people, make a sincere apology, and foster trust through open communication.

Conclusion

Maternity care aims always to be safe, effective and responsive. For the great majority, pregnancy and childbirth is a positive and happy experience that culminates in a healthy mother and baby. But on the rare occasions when things go wrong, the effects are life changing. We have brought together evidence from NIHR-funded studies and other sources to help maternity services address the four pillars of good maternity care:

- kind and compassionate care

- teamwork with a common purpose

- capacity to identify poor performance

- organisational oversight and response to challenge.

The East Kent report emphasised the need for every interaction with mothers and families to be based on kindness and respect. Services need to be culturally sensitive and support individual needs. Care continuity improves the quality of experience and care. High-quality bereavement care, including empathetic and considerate language, can help families who are grieving. In addition, there is a need for more emphasis on improving bereavement care for men.

Good teamwork requires active support. Team members need to understand and value each other's roles, skills and competencies. Teams need to have shared objectives and meet regularly to review their effectiveness. Open discussion and reference to shared goals can help resolve differences. As well as working together, teams need to train together.

The quality of data on safety and performance needs to be improved and considered along with patient and staff feedback. There are rich learning opportunities in patient complaints and patient safety incidents. Action plans generated from local learning need to be audited. The Healthcare Safety Investigations Branch investigations also provide opportunities for learning.

The hospital board has a critical role in supporting a culture of continuous improvement. Using data for quality improvement, not just assurance, is essential, along with actively seeking feedback from staff and patients. Effective clinical leaders can provide an important link between ‘the board and the ward’.

These four factors provide a firm foundation for high-quality maternity care. However, all need support from the wider system, including measures to ensure safe staffing levels and a high-quality care environment.

National programmes and reviews supporting maternity services

- NHSE - Three year delivery plan for maternity and neonatal services

- Better Births (National Maternity review)

- National Maternity Safety Ambition

- Maternity Transformation Programme

- Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch Maternity Programme

- Local Maternity Systems

You may be interested to read

The figure shows concentric circles listing the 5 roles and behaviours healthcare boards should display and the outcomes they can be measured by.

| Board role | Behaviour | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Coach | Collaborative / inquiring | Service improvement / performance excellence |

| Diplomat | Ambassadorial / curious | Improved reputation and relationships |

| Conscience | Listening / questioning | Sustainable organisation |

| Shock absorber | Courageous / probing | Equilibrium of interests |

| Sensor | Challenging / supportive | Risk minimisation / patient safety |

Author: Candace Imison, Deputy Director of Dissemination and Knowledge Mobilisation, NIHR, and Brendan Deeney, Science Writer, NIHR

How to cite this Collection: NIHR Evidence; Maternity services: evidence to support improvement; May 2023; doi: 10.3310/nihrevidence_58172

Disclaimer: This publication is not a substitute for professional healthcare advice. It provides information based on research which is funded or supported by the NIHR. Please note that views expressed are those of the author(s) and reviewer(s) at the time of publication. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

NIHR Evidence is covered by the creative commons, CC-BY licence. Written content and infographics may be freely reproduced provided that suitable acknowledgement is made. Note, this licence excludes comments and images made by third parties, audiovisual content, and linked content on other websites.