People living with severe mental illness often have poorer physical health than the general population. They are much more likely to die below the age of 75, mostly from physical illnesses that could have been prevented.

They are also more likely to have multiple physical health conditions alongside their mental illness, and this increases the complexity of their care.

But poor outcomes are not inevitable. Physical health can be improved, and many early deaths avoided, if people receive the support they need, when they need it.

This Collection brings together recent examples of published and ongoing research, funded or supported by the NIHR. It provides evidence to support the physical health of people with severe mental illness. Much of the research has been highlighted in accessible summaries ‚Äď NIHR Alerts ‚Äď over the last 3 years.

The information included is intended for healthcare professionals involved in the physical and mental healthcare of people with severe mental illness, as well as for those managing and commissioning services.

Key messages

Personalised support – Coping with severe mental illness and multiple physical health conditions can be overwhelming. People prioritise dealing with their mental illness. They need support to self-manage their physical health in a way that is personalised and recognises and addresses the challenges they face.

Improved physical healthcare – Suggestions include care that combines the management of both physical and mental health conditions, good social support, sharing of patient records across different services, and longer consultations to discuss physical and mental health needs.

Annual Physical Health Checks – People with severe mental illness who have their annual physical health check have fewer A&E attendances and unplanned hospital admissions. Only about half of those eligible have them.

Increased uptake of health checks – Telephone invitations, text message reminders and opportunistic invitations improve uptake in the general population and may help this vulnerable group.

A healthy lifestyle – A healthy lifestyle is associated with a longer life in people with multiple mental and physical health conditions, as much as for people without.

Targeting single versus multiple health behaviours – Smoking may be better targeted alone rather than with other behaviours for people with severe mental illness. By contrast, interventions targeting diet alone, physical activity alone or both together can all promote weight loss.

Addressing clusters of multiple health conditions – People with severe mental illness are more likely to have multiple physical health conditions than their peers, and at a younger age. It is now known that these conditions tend to group together in similar clusters, whether or not people have severe mental illness. Services could focus on these disease clusters for both groups, but with intervention starting earlier for people with mental illness.

Extra support after an inpatient stay – People with severe mental illness who have been recently discharged from inpatient mental healthcare need extra support for their physical and mental health. They are more likely to die of natural causes and by suicide than those who have not recently been in hospital. More deaths from natural causes occur in the first year after discharge, especially in the first 3 months.

End of life care – Barriers exist to good end of life care for people with severe mental illness. The relevant services – and the practice of professionals within them – are different. Collaborative working across mental health and end of life care systems, training, and proactive physical health care could improve care.

Introduction: Health inequality

It is well-documented that people with severe mental illness, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and other psychoses, face health inequalities and often have poorer physical health than the general population. On average, their lives are 15 to 20 years shorter, mostly because of preventable physical illnesses.

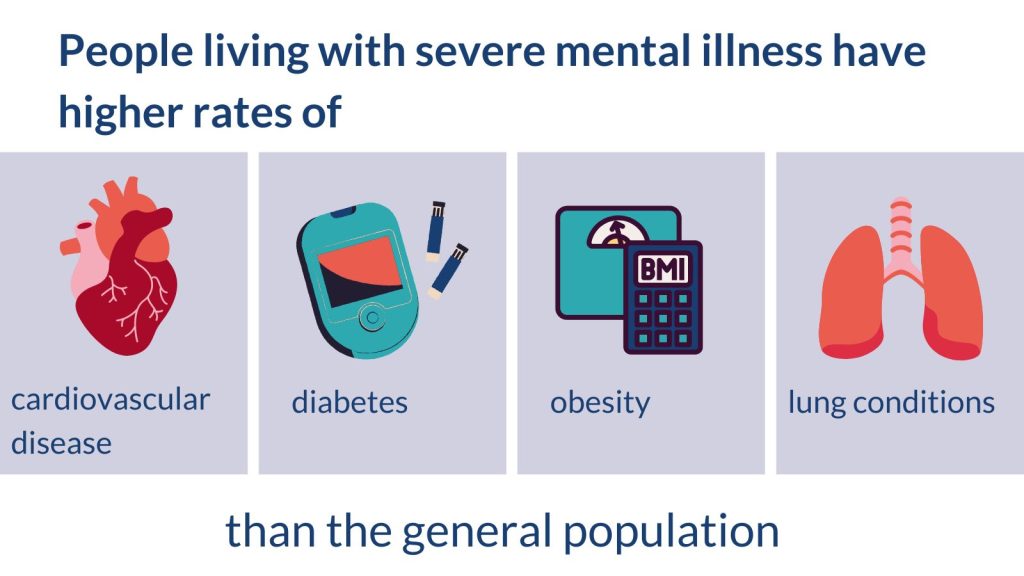

They have higher rates of cardiovascular disease (such as heart disease and stroke), diabetes, obesity and lung conditions (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or COPD, and asthma). They are also more likely to have multiple physical health conditions than the general population. This is particularly true for young people with severe mental illness; those aged 15 to 34 years are 5 times more likely to have 3 or more physical health conditions.

The reasons for poorer health among people with severe mental illness are complex and not fully understood, but mental and physical health conditions are often connected. For example, the side effects of medication used to treat severe mental illness (antipsychotics) can include increases in weight, blood sugar levels, and blood pressure. These in turn increase the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Higher rates of smoking, poor diet and physical inactivity, as well as social factors such as poverty, lack of employment, stigma and discrimination, also play their part.

Care is not always well coordinated and access to appropriate services can be uneven. Health services can help improve the physical health of people with severe mental illness by bringing together mental and physical healthcare. Taking a ‚Äėwhole person‚Äô integrated approach, which addresses the interactions between physical and mental health, could help people live longer, healthier lives.

This idea is not new, but there is still some way to go. The need for integrated care was a key component of the Five Year Forward View for Mental Health in 2016. By September 2022, 1 in 3 (34%) primary care networks had partially or fully implemented new models of care, and improved coordination between NHS mental and physical health services. The move to Integrated Care Systems in England requires different parts of the NHS (including hospitals, primary care and community and mental health services) and social care to work in a more joined-up way. This should further improve the support available.

Checkups for physical health

Health checks

Health checks can spot signs of physical health conditions such as heart disease and type 2 diabetes. People with severe mental illness are at greater risk of these long-term conditions than others. GP surgeries offer annual physical health checks, including measurements of weight, blood pressure, blood sugar and cholesterol.

The importance of these health checks for people with severe mental illness was demonstrated in a recent study. Having an annual physical health check in the previous 12 months was associated with reductions of 20% in A&E attendances, 25% in mental illness admissions, and 24% in emergency admissions for ambulatory care sensitive conditions such as asthma, diabetes and flu (for which effective community care can help prevent the need for hospital admission).

Although numbers are increasing, many of those eligible do not take up their health check. In the 12 months up to December 2022, only about half of people with severe mental illness in England (256,256 out of 535,808) had an annual health check. The NHS Long Term Plan commits to increasing this number to 390,000 by 2023-24.

Cancer screening

People with a mental illness are less likely to be screened for cancer than the general population; they are also more likely to die from the disease. A recent review from across the world found the screening gap was particularly high for women with schizophrenia. They were half as likely to receive breast cancer screening as women in the general population.

Increase uptake of health checks and screening

Further efforts are needed to increase uptake of physical health checks and cancer screening in this vulnerable group. Methods that increase uptake of NHS Health Checks in the general population may help. Telephone invitations and text message reminders were more effective than letters. Automated prompts on GPs’ computers also improved uptake, especially for men and younger people. Verbal invitations, given when an opportunity arose, were helpful; they could be used to selectively target specific groups at greater risk, as well as those who are less likely to engage with health checks.

Healthy living

Intervention as part of routine care

A healthy lifestyle, such as eating a balanced diet, taking regular exercise, and avoiding smoking and excess alcohol consumption, can improve health and increase lifespan. A recent study found this was as true for people with multiple (2 or more) long-term physical and/or mental health conditions, as for anyone else.

The study considered 36 different health conditions, ranging from diabetes and depression to osteoporosis and schizophrenia. Regardless of how many conditions someone had, a healthier lifestyle was associated with 6 years of longer life for men and 7 years for women. Not smoking had the greatest effect.

In 2019, a major publication from the Lancet Psychiatry Commission, supported by the NIHR, reviewed what was known about physical health in people with mental illness, and provided actions for policy, services and research. It included a review of lifestyle factors, such as smoking, poor diet and inactivity, that contribute to the poorer physical health of people with mental illness. It found that people with mental illness, especially those with schizophrenia, tend to have more unhealthy lifestyles than others in the general population. The report gave examples of interventions, including a bespoke smoking cessation intervention, and called for the adoption, translation and routine provision of evidence-based lifestyle interventions as a routine part of mental healthcare.

Whether to target one behaviour or many

A more recent review of 101 studies looked at whether it is better to focus on changing one lifestyle behaviour at a time (such as smoking), or whether to target multiple behaviours at once for people with severe mental illness.

‚Äú[M]y big goal is to be fully recovered from all the physical and psychological problems I‚Äôve got. That‚Äôs my goal, to be fully recovered.‚ÄĚ

Service user

Evidence was limited, and most health improvements were small. But findings suggested that focusing on quitting smoking alone may be better than targeting other behaviours, such as an unhealthy diet, at the same time. By contrast, interventions targeting diet alone, physical activity alone or diet and physical activity together, appeared to be similarly effective in promoting weight loss and reduction in body mass index. There was no evidence that trying to improve physical health worsened the mental health of people with severe mental illness. People favoured interventions that took their condition into account, and promoted physical and mental health together. However, most trials focused on promoting physical health.

Managing physical health

Clusters of physical health conditions

People with severe mental illness have higher rates of physical illness than the general population. Many have more than one physical health condition.

A large database study included people with and without severe mental illness. It looked at how common it is for people to have multiple physical conditions and which ones are commonly found together. 24 physical health conditions were considered. People with severe mental illness were more likely to have risk factors for poor health, such as smoking, obesity or substance misuse. They had more physical health conditions, particularly at a younger age. Physical health conditions clustered similarly in both groups. This suggests that services for people with severe mental illness could focus on the same disease clusters as in the general population, but that intervention may need to begin at an earlier age. (Clusters of multiple long-term conditions have been discussed in a previous NIHR Evidence Collection).

The challenges of living with mental and physical illness

‚Äú. . . you stop caring, it‚Äôs like, if you stop caring about yourself, or what happens to you, it‚Äôs very difficult then, for someone to say, ‚Äėwell you need to stop eating these, these and these‚Äô. It‚Äôs very, very difficult.‚ÄĚ

Service user

Interactions between mental and physical health conditions increase the challenges for people with severe mental illness. Recent research sought to understand what helps or hinders people with severe mental illness from self-managing long-term physical health conditions.

Two studies on people with severe mental illness produced similar insights. In the first study, people had 1 or more physical health conditions; in the second study, people had diabetes, and many also had additional physical health conditions.

People in both studies frequently found it overwhelming to deal with their mental illness and multiple physical health conditions. They put dealing with their mental illness first. The studies concluded that, to self-manage their physical health, people need support that is tailored to their individual needs and recognises the challenges they face. Both stressed the importance of good social support, and for services that bring together physical and mental healthcare.

"I have a community nurse that comes every fortnight who gives me my injection and she will sit with me for a good half an hour and I can offload to her and it’s really good that I can have that time and if anything goes wrong, she can get me an appointment to see my psychiatrist, straightaway if I need to."

Service user

The first study also highlighted the need for longer consultations in which to discuss both physical and mental health conditions.

The second study concluded that diabetes knowledge and better mental health (like improved mood) helped people with severe mental illness manage their diabetes.

Care after discharge from inpatient mental healthcare

People with severe mental illness who have been recently discharged from inpatient mental healthcare need extra support for their physical and mental health. A recent study found that these people have an increased risk of dying of natural causes and by suicide (compared to those with severe mental illness who have not recently been in hospital). Death from natural causes was higher in the first year after discharge, but especially in the first 3 months. This suggests a need for careful discharge planning, follow-up and support after a hospital stay.

Better end of life care

The complex care needs of people with severe mental illness can lead to inequity in end of life care. This group needs the same palliative services as everyone else. However, it is often unclear who is best placed to manage their care. Mental health staff may not feel equipped to manage end of life care; end of life care specialists may feel unable to treat someone with severe mental illness.

A new review identified barriers to end of life care, including staff attitudes and access to services. It also found that people with severe mental illness might not recognise their physical health needs and signs of deterioration. They are therefore often late to receive palliative care. The review recommended collaborative working across mental health and end of life care systems, training, and proactive physical health care. These and other measures would help ensure that people with severe mental illness receive appropriate end of life care.

Conclusion

People with severe mental illness face unique challenges looking after their mental and physical health. These challenges can be overwhelming, and people tend to prioritise their mental health. But they have worse physical health than others in the population. Their higher rates of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, and lung conditions may be partly due to higher rates of smoking, poor diet and physical inactivity. They also face social challenges and are more likely than others to live in poverty, lack employment and face discrimination.

While their need for improved physical healthcare, and health promotion, is great, they struggle more than others to access good care. People with severe mental illness need personalised support from services, delivered in ways they find helpful. Research highlighted in this Collection makes suggestions which could improve care. They are summarised in our Key Messages above.

Caring for the physical health of people with severe mental illness is complex. They need support from services across the healthcare system. Integrated physical and mental healthcare has been seen as the way forward for many years and it will be enabled by the current move to Integrated Care Systems. This Collection has brought together examples from NIHR research that could inform future care for this vulnerable group.

Examples of ongoing NIHR research supporting the physical health of people with severe mental illness

- Supporting Physical and Activity through Co-production in people with Severe Mental Illness (SPACES)

- Developing and evaluating a diabetes self-management intervention for people with severe mental illness: The DIAMONDS programme (Diabetes and Mental Illness, Improving Outcomes and Self-management)

- MoreRESPECT: A Randomised controlled trial of a sexual health promotion intervention for people with severe mental illness delivered in community mental health settings

- REalist Synthesis Of non-pharmacologicaL interVEntions for antipsychotic-induced weight gain (RESOLVE) in people living with Severe Mental Illness (SMI)

- Promoting Smoking CEssation and PrevenTing RElapse to tobacco use following a smokefree mental health inpatient stay: the SCEPTRE programme

- Developing and user testing iSWITCHED (implementing SWITCHing EDucational intervention) to support switching antipsychotics to improve physical health outcomes in people with severe mental Illness

- An intervention using mental health support workers as link workers to improve dental visiting in people with severe mental illness: A feasibility study

- A cognitive intervention to increase physical activity in people with schizophrenia

Author: Jemma Kwint, Senior Research Fellow (Evidence), NIHR

How to cite this Collection: NIHR Evidence; Supporting the physical health of people with severe mental illness; April 2023; doi: 10.3310/nihrevidence_57597

Disclaimer: This publication is not a substitute for professional healthcare advice. It provides information based on research which is funded or supported by the NIHR. Please note that views expressed are those of the author(s) and reviewer(s) at the time of publication. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

NIHR Evidence is covered by the creative commons, CC-BY licence. Written content and infographics may be freely reproduced provided that suitable acknowledgement is made. Note, this licence excludes comments and images made by third parties, audiovisual content, and linked content on other websites.