Read below to discover what research tells us about how antidepressants are being prescribed for children and teenagers and which antidepressants are effective for depression and anxiety.

Mental health care for children and teenagers: introduction

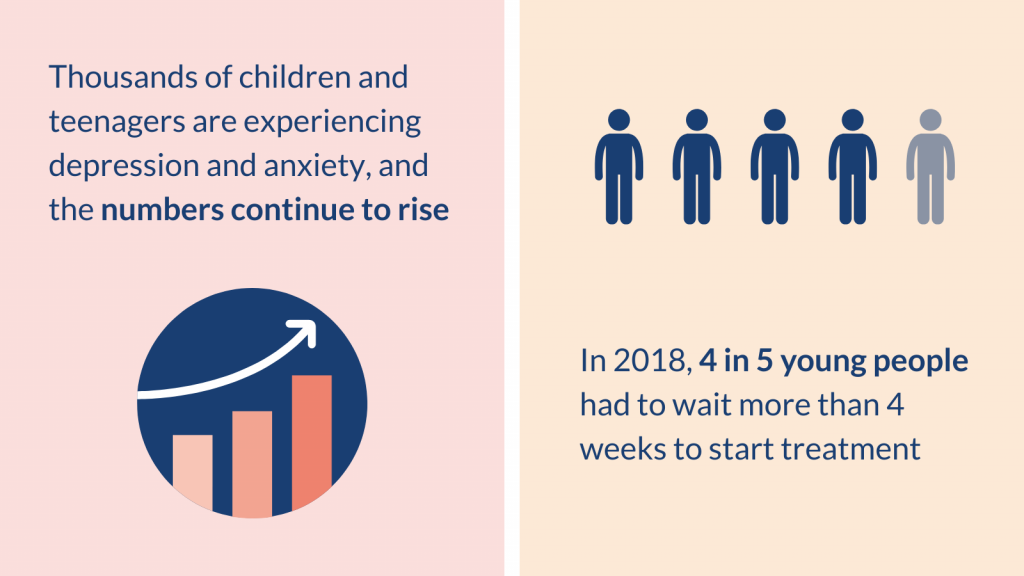

More and more children and teenagers have poor mental health. For some, it was made even worse by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Depression and anxiety are particularly common. These mental health conditions can greatly affect young people’s school attendance, relationships with their family and friends, loneliness and sleep. It is vital they receive the help they need as early as possible to prevent lasting mental health difficulties, including serious problems such as suicide attempts.

Psychological (talking) therapies are considered the main treatment. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends these therapies as the first treatment for depression and anxiety in children and teenagers. Unfortunately, they are not always available.

Antidepressants are another important treatment option, but their use is controversial. There are only limited studies on how well they work, and how safe they may be, particularly in certain groups such as younger children.

Addressing young people’s mental health is a national priority and a focus of the NHS Long Term Plan. However, mental health services struggle to meet demand. Many young people cannot access the help they need, or have to wait a long time for treatment. In 2018, 4 in 5 young people had to wait more than 4 weeks to start treatment, with many waiting months.

This Collection brings together accessible summaries of research - NIHR Alerts – and other high quality reviews supported by the NIHR. They were all published in the last couple of years. The Collection covers evidence on antidepressants for children and teenagers, including how they are being prescribed, and their effectiveness and safety for depression and anxiety disorders.

The Collection provides useful information for members of the public, as well as for GPs and other healthcare professionals who treat these vulnerable young people.

Podcast: How to help young people with depression

In this podcast, we discuss the help available for young people with depression, and the times when antidepressants could be the right choice. Read a full transcript of the episode here.

In this Collection

- Trends in prescribing antidepressants

- Which antidepressants are effective and safe for children and teenagers?

- Conclusion

- NIHR-supported studies included in the Collection

Trends in prescribing antidepressants

Prescriptions for teenagers are rising

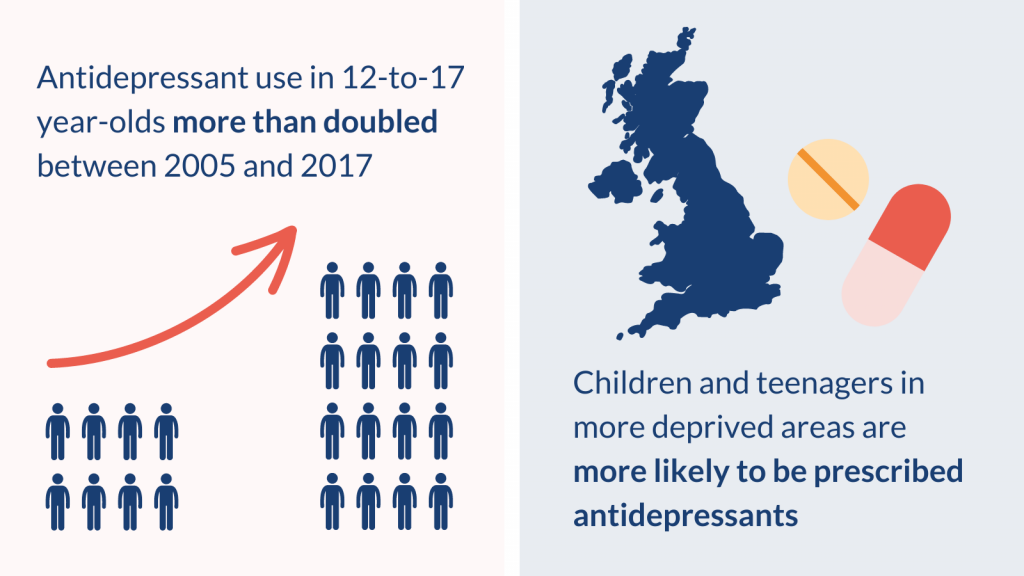

Antidepressants are prescribed to children and teenagers for a variety of reasons, including depression, anxiety, pain and bedwetting. The way GPs in England prescribe antidepressants has changed over time. Research found that the number of 12 to 17 year olds prescribed antidepressants more than doubled between 2005 and 2017. By contrast, prescriptions for 5 to 11 year olds decreased between 1999 and 2017.

Prescribing varied according to where the children and teenagers lived and their ethnic group. Those in more deprived areas were more likely to be prescribed antidepressants. Prescriptions for two antidepressants from a class of drugs called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) increased most over the study period. Those drugs were fluoxetine (Prozac) and sertraline (Lustral).

More recent information suggests that prescriptions have continued to increase, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Many teenagers are prescribed antidepressants without seeing a specialist

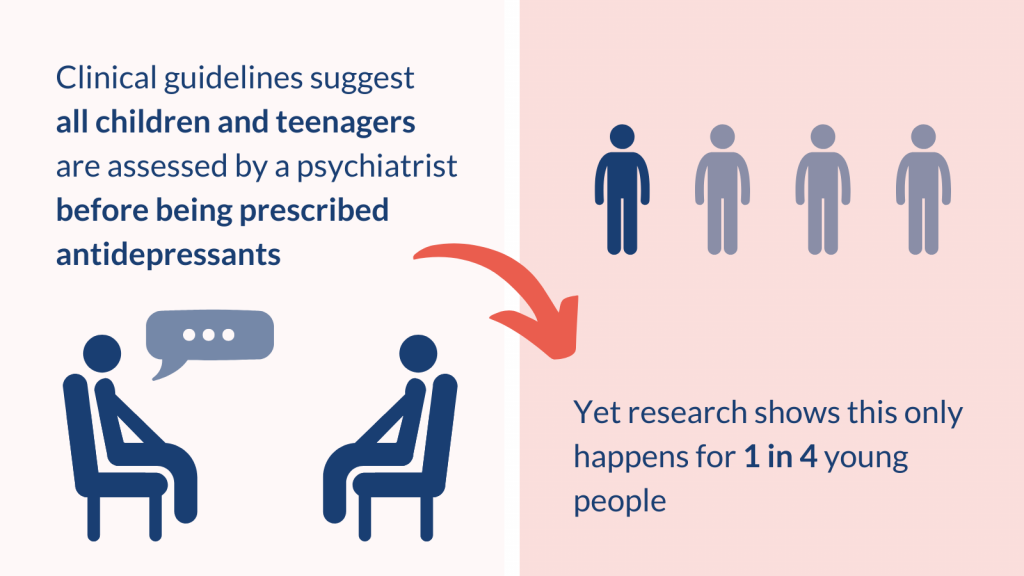

Clinical guidelines from NICE for treating depression and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) (an anxiety disorder, described below) recommend selected antidepressants for children and teenagers. But the guidelines state that these medicines should be given alongside talking therapies, and only after assessment by a child and adolescent psychiatrist (a specialist mental health doctor). Recent research suggests this often does not happen.

A study included a large group of 12 to 17 year olds (more than 21,000) who were prescribed SSRI antidepressants for the first time by their GP between 2006 to 2017. It found that only 1 in 4 of the teenagers had visited a child and adolescent psychiatrist. 1 in 6 had visited a general specialist children’s doctor (a paediatrician), and 1 in 25 had attended adult mental health services. Just over half of their prescriptions were for depression (53%), with the next most common reason being for anxiety (16%). The most commonly prescribed SSRIs were fluoxetine, followed by sertraline and citalopram (Celexa).

There is a need to understand why GPs prescribe antidepressants to teenagers and what prevents them following guidelines. It may be that the recommended talking therapies are not available, or that there are long waiting times for specialist services (average 53 days in 2018/2019). If a GP feels a teenager needs urgent treatment for their mental health condition, and psychological therapies are not immediately available, they may prescribe antidepressants despite the guidelines.

Which antidepressants are effective and safe for children and teenagers?

Depression: Fluoxetine may be the best antidepressant and venlafaxine should be avoided

Where does the evidence come from?

Five recent reviews supported by the NIHR drew conclusions on the effectiveness and/or safety of antidepressants used for treating depression in children and young people.

All reviews included randomised controlled trials, which are the best source of evidence available. However, there is much less evidence for children and young people than for adults, and it is more uncertain. For example, a review of antidepressants for depression in adults included 522 trials, whereas a similar review in children and adolescents included 26 trials.

What does the evidence tell us?

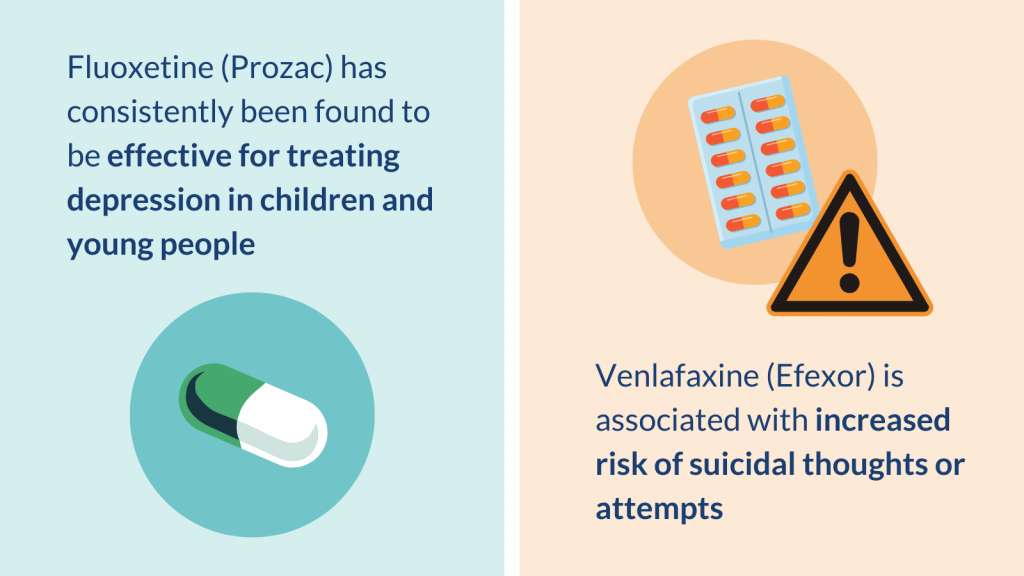

All reviews found fluoxetine (Prozac) to be more effective for treating depression than placebo (a dummy pill that does not contain any medicine). Fluoxetine was also effective when combined with cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). The combination may be better than either treatment alone, although one review reported that it was no different to fluoxetine by itself.

Sertraline (Lustral), escitalopram (Cipralex), and duloxetine (Cymbalta and Yentreve) may also reduce depressive symptoms. One major review found all these antidepressants reduced symptoms more than placebo. However, the overall effects were small.

All reviews found that the antidepressant venlafaxine (Efexor) was associated with an increased risk of suicidal thoughts or attempts, compared to placebo. The findings for other antidepressants were more uncertain and more research is needed (described below). This highlights the need for young people taking antidepressants to be carefully monitored for suicidal thoughts and behaviours.

How do these findings fit with clinical guidelines?

NICE clinical guidance for depression (last updated in 2019) recommends psychological therapies alone (such as CBT within a group) for children and teenagers with mild depression. For those with moderate to severe depression, NICE recommends more intense psychological therapies (such as individual CBT) as initial treatment. However, the guidelines state that combined therapy (fluoxetine and psychological therapy) is an alternative initial treatment for 12 to 18 year olds after assessment by a specialist.

The reviews in this Collection broadly support this approach. Fluoxetine was consistently found to be more effective than placebo. The major review mentioned above concludes that the guidelines could be broadened to include sertraline, escitalopram and duloxetine.

What’s next?

The reviews were comprehensive but were based on relatively poor-quality studies. Uncertainty remains over the use of antidepressants to treat depression in young people. More research is needed, especially on whether these medicines can increase suicidal thoughts and behaviours.

Most trials included in the reviews did not include children and teenagers at risk of suicide. In the ‘real world’, young people seeking help for depression may have suicidal thoughts. Excluding this group from studies weakens their conclusions about antidepressants. Patients, carers and clinicians should continue to balance carefully the potential benefits of treatments with how acceptable they are, and the possible risk of suicide in a young person with depression. Psychological therapies, as recommended in guidance, remain an important part of any treatment approach.

Anxiety disorders: Fluvoxamine, sertraline and fluoxetine may help

Where does the evidence come from?

Three recent reviews supported by the NIHR drew conclusions on the effectiveness and/or safety of antidepressants used for treating anxiety disorders in children and young people. OCD is usually considered to be an anxiety disorder but is considered separately in the reviews and in this Collection. People with OCD have unwanted thoughts or urges (obsessions) and may use repetitive behaviours (compulsions) to relieve the unpleasant feelings.

What does the evidence tell us?

Anxiety disorders

Fluvoxamine (Faverin) was consistently found to be more effective than placebo (a dummy pill) for treating anxiety disorders. Other SSRIs (fluoxetine, sertraline and paroxetine) were more effective than placebo by some but not all measures of anxiety (depending on the specific assessment tool used).

Sertraline (Lustral) consistently reduced the risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviours in young people more than placebo. Paroxetine (Seroxat) increased them.

OCD

Sertraline and fluoxetine (Prozac) were consistently found to be more effective than placebo for treating OCD. The combination of sertraline and CBT was also effective according to one review.

The reviews did not contain information about risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviours in OCD.

How do these findings fit with clinical guidelines?

NICE guidelines do not cover the full range of anxiety disorders. Currently, there are guidelines for children and teenagers for social anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and OCD. All recommend specific psychological therapies as first treatment. Only the guideline for OCD (published in 2005 and due to be updated) recommends antidepressants. When prescribed, NICE states an SSRI antidepressant should be combined with CBT. The reviews in this Collection broadly support this approach for OCD: sertraline and fluoxetine are both SSRIs.

No antidepressants are licensed in the UK for anxiety in children and teenagers under 18 years (except for OCD). Yet both specialists and GPs prescribe them. The reviews in this Collection indicate that certain antidepressants are effective and may be safe. Up to date guidelines are needed for the full range of anxiety disorders in children and teenagers.

What’s next?

Uncertainty remains about the safety of antidepressants in young people with anxiety, especially over the long-term. More research is needed. The limited evidence about suicidal thoughts and behaviours highlights the importance of careful monitoring of children and teenagers taking antidepressants.

Conclusion

Thousands of children and teenagers in the UK are taking antidepressants for depression and anxiety. The numbers continue to rise and many have not seen a specialist.

This Collection brings together recent NIHR evidence showing that some antidepressants are effective and may be safe for children and teenagers. It also highlights uncertainties that remain.

Very few of the studies included in major reviews looked at long-term treatment. Treatment was usually for between 2 and 16 weeks. This is problematic because symptoms of depression and anxiety can last a long time, even into adulthood, and they require long‐term treatment. More research is therefore needed into the effectiveness and safety of long-term antidepressant use in young people.

Clinical guidelines stress the need to involve child and adolescent psychiatrists in decisions to use antidepressants in children and teenagers. We know this often does not happen. Limited access to mental health services and a lack of child and adolescent psychiatrists seem to prevent it. Some GPs start prescribing to help young people in urgent need, which may be life saving if they are very depressed. Treatment decisions need to balance the drugs’ effectiveness with the possible risk of extreme side effects such as suicidal thoughts and behaviours as well as how severely depressed the young person is.

Depression and anxiety can profoundly affect the lives of children and teenagers and all of those around them. Evidence-based treatments, including psychological therapies and antidepressants, can help. But young people must be able to access mental health services they need. In the NHS Long Term Plan, the Government commits to expanding mental health services for children and young people and reducing unnecessary delays. This should improve the support available.

NIHR-supported studies included in the Collection

- Study looking at how prescriptions of antidepressants have changed over time: Teenagers' use of antidepressants is rising with variations across regions and ethnic groups

- Study looking how antidepressants are prescribed to young people: Secondary care specialist visits made by children and young people prescribed antidepressants in primary care: a descriptive study using the QResearch database

- Review about antidepressants for depression in adults: The most effective antidepressants for adults revealed in major review

- Review about antidepressants for depression in young people: New generation antidepressants for depression in children and adolescents: a network meta‐analysis

- Review about antidepressants and psychotherapies for depression in young people: Prozac may be the best treatment for young people with depression – but more research is needed

- Review about antidepressants for several conditions, including depression and anxiety: Antidepressants in Children and Adolescents: Meta-Review of Efficacy, Tolerability and Suicidality in Acute Treatment

- Review about several drugs and conditions, including antidepressants for depression and anxiety: Psychiatric drugs given to children and adolescents have been ranked in order of safety

- Review about several drug and non-drug treatments and conditions, including antidepressants for depression and anxiety: Efficacy and acceptability of pharmacological, psychosocial, and brain stimulation interventions in children and adolescents with mental disorders: an umbrella review

How to cite this Collection: NIHR Evidence; Antidepressants for children and teenagers: what works for anxiety and depression?; November 2022; doi: 10.3310/nihrevidence_53342

Author: Jemma Kwint, Senior Research Fellow (Evidence), NIHR

Disclaimer: This publication is not a substitute for professional healthcare advice. It provides information about research which is funded or supported by the NIHR. Please note that views expressed are those of the author(s) and reviewer(s) at the time of publication. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

NIHR Evidence is covered by the creative commons, CC-BY licence. Written content and infographics may be freely reproduced provided that suitable acknowledgement is made. Note, this licence excludes comments and images made by third parties, audiovisual content, and linked content on other websites.