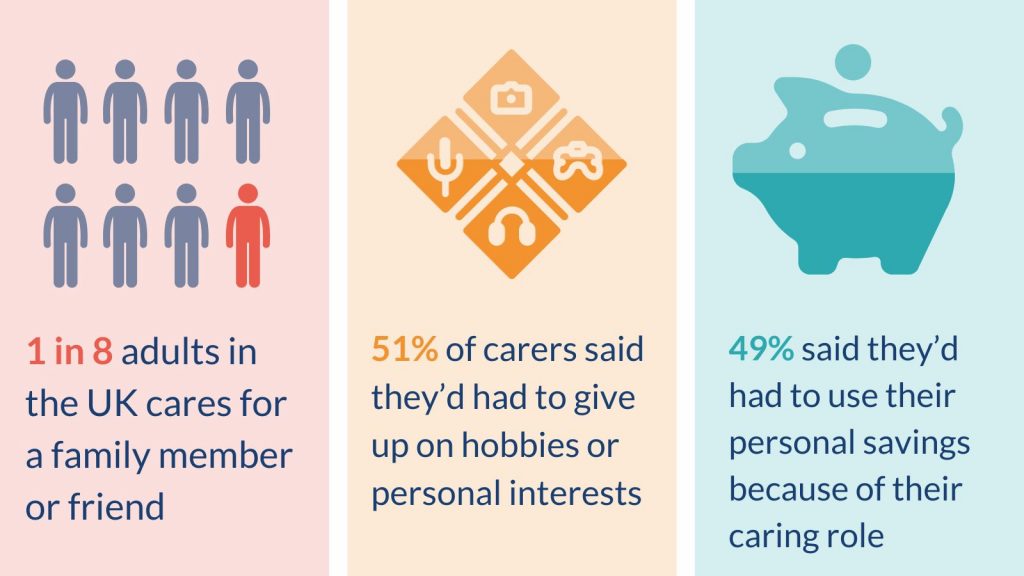

Approximately 6.5 million people across the UK are carers. That means 1 in 8 adults are caring for family members or friends.

These individuals are unpaid, but they dedicate their time to supporting someone who needs help in their daily life. Some might not even think of themselves as carers. They are simply doing what they can to help a loved one. The relationships between carers and the people they care for varies. Carers might be looking after their child, spouse, parent, neighbour or a friend.

“Being a family carer is not something I set out to do or be - it crept up on me. I did what was needed because I care and want the person I love to live the best life they can. Then one day there it was - I was, unexpectedly, a ‘carer'.

Una Rennard, lived experience

The UK has a growing population of older people. Alongside this, people with long-term conditions are living longer. This means more people need care for longer periods of time. Some estimates suggest the care provided by family and friends is worth £119 billion every year. Research from Carers UK shows that carers want to be recognised and valued for what they do, to have the information to be able to care well and safely, and to make the right decisions for themselves and their family.

This Collection brings together messages from NIHR research over the past few years. It highlights the impact a caring role can have on people, and explores how the health and care system could support carers. The Collection demonstrates the value of carers’ views in research.

This Collection demonstrates how research could help improve the daily lives of carers. It aims to help health and care professionals understand how they can support people with a caring role.

The impact of being a carer

Caring can have a huge impact on someone’s life. In a survey from the Carers Trust, half the carers (51%) said they had given up on hobbies or personal interests; similar numbers (49%) had needed to use their personal savings because of their caring role. Could research help us to understand the impact of caring for a loved one?

“When you do identify as a carer it can be challenging. For me it can change how others see me and sometimes it means I ‘lose’ the essence of who I am; for the person I ‘care’ for it means they can be seen as someone who needs care rather than as an individual with autonomy.”

Una Rennard, lived experience

Carers often take on extra responsibilities they know little about. For example, research has shown that older people and family carers can find managing lots of medications difficult. Carers may also need to make difficult decisions about their loved one's care. One of their biggest concerns is being unable to take breaks. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this became even more challenging. To protect their household, some family carers chose to stop paid carers coming into the home during lockdowns. For carers, support services were paused. This meant the unpaid carers had more to do and they had to take on care jobs they were not trained for.

Physical and mental health

These responsibilities can have an effect on the carer’s mental and physical health. In one study, researchers interviewed family members who were caring for people with dementia. Most (2 in 3) said they felt lonely. Not only is loneliness distressing, it can also impact physical health. It has been linked to heart disease, stroke, depression, cognitive decline and early death.

Another study looked at mothers of children with life-limiting conditions. These women not only carry the burden of knowing their child will die early, but they often also provide full-time care. Researchers found these mothers had a higher risk of common health problems compared with the mothers of healthy children. This included depression and heart disease. They were also more likely to die early.

“I have experience of caring for a close friend who has dementia. At times this has left me stressed and not allowed me the time I need to properly look after myself. So for example I have neglected my diet and not allowed time for exercise. All of this has had an effect on my overall health.”

Debs Smith, lived experience

“Whether I am a carer or not, the ‘role’ I take on can be emotionally and mentally draining and undoubtedly has an impact on my physical health.”

Una Rennard, lived experience

Financial impact

Caring does not only affect health, caring can have a serious financial impact. With the rising cost of living, the financial impact of caring is growing. Many carers need to give up or reduce their employment, rely on charities for basic necessities, and pay for expensive services or equipment to support their loved one. Some people are eligible for Carer’s Allowance, but 1 in 5 carers are worried about being able to cope financially.

For young people, caring can reduce their opportunities in the short- and long-term. Research found that young adult carers are more likely to be unemployed and to have lower earnings from paid work. The researchers looked at the employment, earning and health impacts of young adult carers, aged 16 to 25. They compared them with non-carers of the same age. The researchers found that young adult carers had worse physical and mental health than other young people. They also had worse economic prospects. The study found these negative effects on young carers cost the UK economy 1 billion pounds each year.

How could we support unpaid carers?

People who provide care for their family and friends can get financial support. They could also be eligible for practical help from their local council. But more is needed. Research has been looking at how services could help carers manage their health and wellbeing.

Online resources

Many who care for people with dementia have anxiety or depression. Support groups for carers can be helpful, but people might not be able to attend in person. Researchers have found an online package of practical information and advice could help carers manage their mental health. The study also showed cognitive behavioural therapy combined with telephone support was useful. However, this was more time-consuming to provide. The team is exploring how to deliver the online package more widely.

Support for daily tasks

Other research suggested a few simple interventions to help carers manage medication, For example, a short questionnaire could identify people who are struggling. Professionals should work with older people and their carers to produce personalised information (such as a daily checklist). This allows carers and their loved ones to feel that they are in control, and managing their own care.

Having a job outside the home may be helpful for some. People looking after relatives with dementia were asked to fill in a questionnaire. This research showed carers have a better quality of life if they also work outside the home. This research calls for support for working carers, for example, through flexible working hours.

“Hearing that researchers have said carers are better if they have some form of job as well as being a carer will mean carers are more likely to feel they can work without feeling guilty. I think this can be another way of carers learning not to neglect themselves as I so often have.”

Debs Smith, lived experience

Keep carers in mind

Many carers have regular contact with health and care providers. However, appointments usually focus on those they care for, rather than themselves. Health and care professionals might consider proactively including carers. For example, mothers of children with life-limiting conditions are in close contact with healthcare services for their children. However, these women visit their GP less often than the mothers of healthy children. Research suggests that the child’s doctors and nurses could be more active in encouraging parents to access physical and mental healthcare services. Targeted interventions could encourage mothers to visit their GP for any health concerns.

Other approaches that could support carers include face-to-face support from a dementia care coach, resources to help with end-of-life planning and training to communicate with loved ones. This research is ongoing. You can find out more about the research happening now on our Funding and Awards site.

“In my experience helping someone to navigate complex systems and maintain their independence and autonomy, especially when it feels like the system is designed to ‘disable’ people rather than encourage autonomy and independence, is exhausting. It is not the ‘caring’ itself that wears you down. It’s great that the research recognises the impact on carers but we need to understand the causes in order to find solutions.”

Una Rennard, lived experience

How can carers influence research?

Not only could research help spotlight and support carers, but carers can improve the relevance of research by speaking up for themselves and their loved ones. People affected by research are in an ideal position to make sure studies are useful. The NIHR gives people a say in designing and running research. Often researchers focus on people living with a disease or condition. But studies also benefit from the perspectives of carers.

For example, one study explored the views of carers within Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities to understand the risk of forced marriage among people with learning disabilities. Carers highlighted the importance of marriage within South Asian communities, and the idea that marriage could be a way to secure long-term care. These findings could help professionals, parents and carers recognise and prevent forced marriage.

Other research looked at the support people with learning disabilities need to form loving relationships. Speaking to family carers highlighted the benefits of specialist dating agencies, but also raised concerns around families wanting to protect loved ones from the risks of dating and relationships.

Research does not have to be about carers to involve carers. They often have valuable insights into the challenges facing the person they care for. For example, when people with dementia go into hospital, decisions about future care might be needed. Many family carers felt their knowledge about their relative’s life history, key relationships and usual behaviours were not valued. The study found there was a need for earlier discussions between staff, people with dementia, and their families after hospital admission.

Conclusion

This Collection underlines the impact that caring can have on someone’s mental health, physical health and economic circumstances. The research explores ways to help carers, through online resources, for example, and by prompting health and care professionals to proactively consider the needs of the carer during healthcare appointments. Action is needed to make these research findings a reality. This includes involving carers in making decisions about their loved ones and supporting them to provide the best care they can.

However, there are barriers that prevent carers from getting the support they need. For example, healthcare professionals might not recognise the challenges of caring. Carers themselves might not identify as carers. Some might not be able to leave their loved one for long enough to go out to work or to follow their own interests.

The experiences of an individual carer are unique. Their needs depend on their situation and the complexities of their life. Much of this Collection focuses on people caring for relatives with dementia. People with other caring needs and other carer relationships appear less well-researched but they are equally in need of understanding and support. Health and care professionals offering support need to be sensitive to the complex dynamics of a caring relationship, and make sure they are listening to the issues presented by the carer.

Finally, this Collection highlights the perspectives carers can give to research. Research funders and teams have a responsibility to involve carers in decisions on funding and in projects. This will ensure that research addresses the questions that are most pressing to carers, and that future solutions are relevant to carers' lives.

You might also be interested in:

Tips for carers to get and stay involved in health and care research

Tips for researchers involving unpaid carers in health and care research

How to cite this Collection: NIHR Evidence: Supporting family and friends: how can research help carers?; October 2022; doi: 10.3310/nihrevidence_54306

Author: Martha Powell, Communications Manager, NIHR

Disclaimer: This publication is not a substitute for professional healthcare advice. It provides information about research which is funded or supported by the NIHR. Please note that the views expressed are those of the author(s) and reviewer(s) at the time of publication. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Photo credit: Centre for Ageing Better

NIHR Evidence is covered by the creative commons, CC-BY licence. Written content and infographics may be freely reproduced provided that suitable acknowledgement is made. Note, this licence excludes comments and images made by third parties, audiovisual content, and linked content on other websites.