- Foreword

- Introduction

- Context

- What are the critical influences on young people's inpatient experience?

- What is the best way to gain insight into young people's inpatient experience?

- How can understanding experience be used to improve inpatient care?

- Overall conclusion

- Illustrations

Foreword

In October 2019, NHSE announced the establishment of a Quality Improvement Taskforce (QIT) for inpatient services for children and young people with a mental health, learning disability and/or autism need. The aim is to drive quality improvements at pace, and, as a CEO of such services, I welcomed this Taskforce. I am pleased that NIHR has developed this Themed Review on patient experience as a fundamental component of improvement work.

The challenges for Children Young People Mental Health (CYPMH), Learning Disability (LD) & Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD) services are many and varied. They are well-documented and include culture, staffing and capacity. So why should the QIT be concerned with the experience of service users? Emerging evidence increasingly suggests that improving patient experience has a positive impact on patient outcome. Improving staff experience increases effectiveness, efficiency and productivity. All these elements are important, of course, and they are all considered by the QIT, but we must ensure that every child or young person in our services knows we are listening to what matters to them.

Improving Care by Using Patient Feedback – a thematic review of nine NIHR funded research studies on the use and usefulness of patient experience data in the NHS was published by NIHR in 2019. It prompted a conversation between QIT and NIHR about how to work together to use the knowledge they had gathered on patient experience to inform the QIT improvement work. The NIHR study (NIHR 2019) suggested there is little meaningful patient experience information available for mental health services, and where it is available, staff do not know how to use it to drive quality improvement. A conversation with the author, Dr Elaine Maxwell, NIHR Clinical Adviser, led to NIHR’s decision to undertake this Themed Review.

This Themed Review offers an opportunity for a QIT programme that will ensure patient experience is considered in real time. This information will facilitate improvements for individual patients at the time that they are experiencing care.

The QIT is grateful to NIHR for considering this topic as one of only three Themed Review during 2020/21 and is committed to using these findings to improve patients’ experience of care.

John Lawlor, Chief Executive, Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust

Introduction

The focus of this review

This Themed Review explores the experience of young people with mental health problems, learning disability or autism in specialist inpatient mental health care. A young person may require admission if their disorder means that they are at high risk of self-harm or pose a risk to others. They may also be admitted if they need more intensive treatment and assessment than is possible in a community setting. This Themed Review does not cover young people's experience of inpatient paediatric care (for physical needs) or issues such as inappropriate admission to adult mental health services.

The quality of a young person's inpatient experience is important for their short and long term therapeutic outcomes. Outcomes include the effectiveness of interventions but also take account of the young person’s progress towards personalised goals. A good quality experience will build trusting relationships with staff and motivate children, young people and their families to engage in treatment. But good experiences require staff to understand what matters to children, young people and their families, and how they perceive the care they receive.

The review asks three key questions about young people’s inpatient experience:

- What are the key influences?

- What is the best way to gain insight?

- How can new understanding be used to improve inpatient care?

We aim to provide insights that will help those seeking to drive improvement in the experience of young people in specialist mental health, learning disability, and autism inpatient care settings.

Methodology and approach

The NIHR shares knowledge and promotes in-depth discussion with the aim of improving health and social care. Our Themed Reviews are an important tool. They include both academic study and practical wisdom from lived experience and are guided by our stakeholders and steering group. Members of the steering group for this review are listed in the acknowledgements.

Themed Reviews are not systematic reviews of all the evidence. Nor are they guidance or recommendations for care. Instead, they are narratives based on a selection of different kinds of evidence chosen to illuminate and inform discussions on actions for practice.

As well as searching the scientific literature, for this Themed Review we consulted children and young people, their parents and staff, to see how far the evidence reflected their experience. We also collected online resources, audits and first-person accounts. Our review combines these different strands of evidence to make sense of current knowledge.

There are many gaps in the evidence, and where appropriate we draw on findings from other settings, including adult inpatient mental health services. Most published research on children and young people comes from Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) rather than learning disability and autism units. There is little evidence on the views of children and young people themselves and, where data is collected, it tends to focus on environmental factors.

Context

Scale of specialist inpatient provision

CAMHS level 4 services provide inpatient care for the assessment and treatment of children and young people with complex emotional, behavioural or mental health difficulties. In January 2021, NHS England commissioned 1350 CAMHS Level 4 beds from a combination of NHS and private providers (personal communication). This included 56 beds (4%) for those with a learning disability and 210 beds (15%) for those with eating disorders. However, children and young people with learning disabilities or special needs such as eating disorders also use the general CAMHS beds. They may therefore be using more beds than the designated numbers suggest.

The average length of stay can be many months. In 2018/19 the average stay on CAMHS inpatient wards was 62 days for general admission, 107 days for eating disorders and 273 days for secure admissions (NHS Benchmarking, 2019).

To set the number of CAMHS beds in context, the total number of mental health beds in 2019/20 in England was just over 18,000 (Ewbank et al., 2020)

A policy priority

The experience of children and young people in specialist mental health, learning disability, and autism inpatient care settings is a national concern and policy priority. A CQC Review of children and young people's mental health services in 2017 found that:

"Some inpatient services were breaching the regulation that requires them to provide personalised care and treatment that meets the needs of people using the service……. Poorly maintained or inappropriate facilities were also common issues for inpatient services."

Inspectors highlighted issues around staffing and access to specialist CAMHS services. Staffing problems are still a significant issue (Gilbert, 2019). There is wide geographical variation in provision. In 2017, this ranged from 1.1 beds per 100,000 in the South West, to 3 per 100,000 in the North West. Some 331 children were admitted to a CAMHS unit which was 50 or more kilometres from their home (Frith, 2017).

The NHS Long Term Plan sets out commitments to improve access to, and the quality of, inpatient care for children and young people with mental health, learning disability and autism, including reductions in the use of restraint.

A specialist Taskforce has been established in recognition that:

"inpatient services are not currently of a high enough quality, and improvements are needed specifically for under 18-year olds."

The Taskforce has a Charter which sets out its ambition:

- No child or young person is admitted unless inpatient care is necessary for them to receive treatment. We will not support admissions to manage a condition or challenging behaviour.

- Alternatives to inpatient care, including intensive support at home or in social care settings, should be offered wherever possible.

- No child who needs an inpatient bed has to wait, or be admitted to units far away from home.

- No child or young person stays in inpatient care any longer than they need to; discharge planning commences at the point of admission.

- Human rights guide decision-making in care.

- The voice of children and young people, and their family or carers, are embedded in the culture, and are taken on board in all decisions about care.

The Charter recognises and seeks to address many of the key issues surrounding inpatient care for young people with mental health problems, learning disability and autism. It acknowledges the risks associated with admission. For example, young people may learn behaviours and make friendships that are harmful. They may also become 'dislocated' from normal life, friends, and education (Hannigan et al., 2015). The Charter therefore states that children and young people should be inpatients only if absolutely necessary.

What are the critical influences on young people's inpatient experience?

We reviewed evidence on the key influences on young people's inpatient experience and tested our findings with young people, their carers and staff. A wide range of contextual and demographic factors have an influence. For example, young people’s experience of inpatient units is coloured by what has immediately before admission and immediately after discharge. Age and ethnicity are important; satisfaction decreases as children get older and is lower among ethnic minority groups (Biering, 2010).

Key influences on experience

Overall, we identify four key influences on how children and young people experience inpatient care. These are drawn from the research evidence base, but also from the experiential evidence provided by children, young people and their parents. The four themes are:

- quality of relationships,

- normality,

- use of restrictive practices,

- expectations and outcomes.

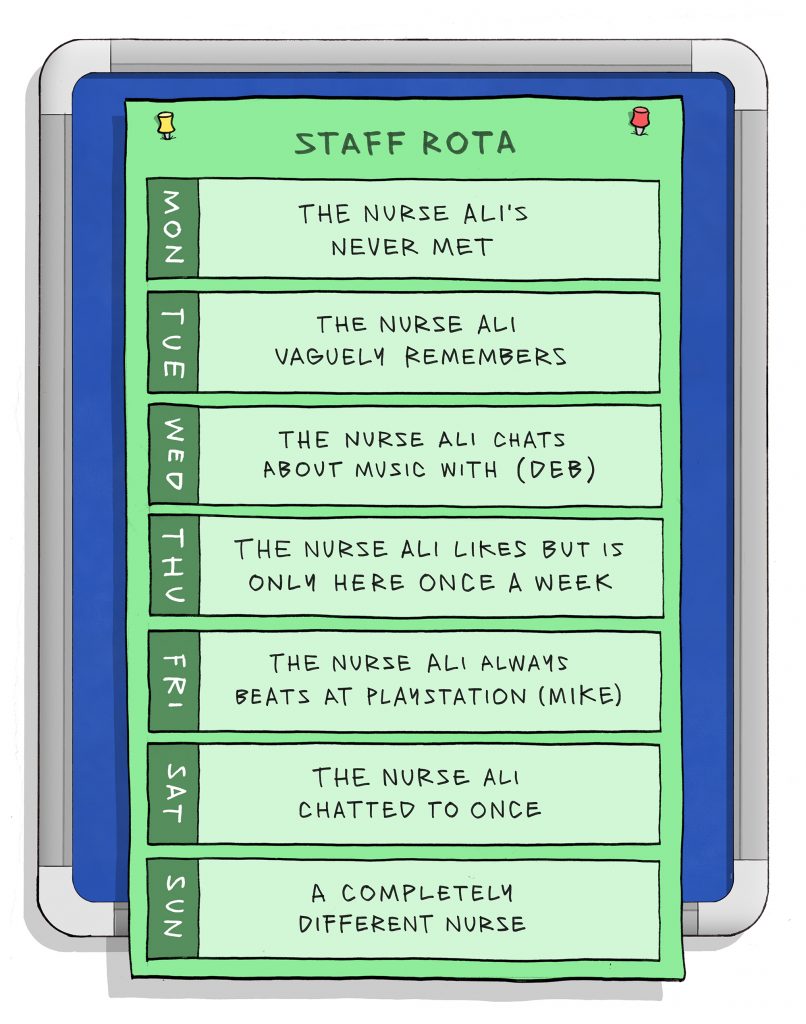

Quality of relationships

For a text description of this image please click here. In addition, you can also download this image and explanation as a PDF poster.

An inpatient admission creates a new set of relationships between a young person, their family, and the staff on the ward. Staff need to have enough time to develop meaningful relationships with the young people they are looking after. Trusting and empathetic acts of care, outside of therapeutic sessions, can improve the quality of a young person's experience and wellbeing.

When a child is admitted to hospital, a new set of interconnected relationships are created between the child, their family, and the staff looking after them (Gross and Goldin, 2008). The quality of relationships and communication between the three groups has a profound effect on a young person’s experience and the outcome of care. Therapeutic relationships are the strongest predictor of good clinical outcomes (Duncan et al., 2009). A critical component is a positive therapeutic alliance between staff, children and their parents (Gross and Goldin, 2008). The therapeutic alliance has been described as having three components:

- mutual agreement and understanding of goals,

- the tasks of each partner, and

- the bonds between partners (Bordin, 1979).

The alliance is strengthened when staff involve young people and their parents in care decisions, show respect and treat them as individuals (Tulloch et al., 2008). Children and young people’s perceptions of their relationships with staff underpin the therapeutic alliance (Garland et al., 2000; Sergeant, 2009).

Relationships with staff outside therapeutic sessions are associated with a good experience and can determine whether the inpatient setting aids recovery (Sergeant, 2009). Young people find the time they spend with staff one of the most valuable aspects of life in hospital (Tulloch et al., 2008). Having someone to listen 24/7 can lead to a shift in perspective that gives hope for the future (Gill, 2014).

“…I think it was the staff that helped because there were these people that were there all the time and I’d never had that before, I never ever had… no-one else had ever been and there were all these staff all around saying, “Do you want to talk?” You know, “Is everything all right?”

The more available and helpful the staff, the higher the satisfaction scores from parents and young people (Tas et al., 2010). Biering (2010) found that good relationships with staff outside therapeutic sessions are associated with good experiences. For young people, a good relationship includes acceptance, empathy, friendliness, and a non‐judgmental approach. Weich et al’s (2020) systematic review of the literature on adult inpatient mental health services backs this up. It noted that good experiences were reported when staff were compassionate, caring and respectful, engaging patients in ways that helped them feel valued and understood. Good experiences reduce the use of coercive measures and promote care that is focused on recovery.

Children and young people describe active engagement with them as acts of ‘care’; for example when staff attempt to read emotional meaning into their behaviour. Connections and trust are essential to enable them to express difficult and complex emotions (Reavey et al., 2017). This echoes Gill’s (2014) doctoral thesis which discussed children and young people’s need to feel understood by others (including by other inpatients).

Reavey (2017) described the nature of relationships on the ward. These relationships determined whether children and young people perceived inpatient units as places of treatment for mental health problems, or as holding places to contain their behaviour. Constant observation and monitoring of behaviour is seen as a poor substitute for care. Kaplan et al. (2001) reported on a US Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Hospital, where staff were perceived to exhibit abusive verbal or physical behaviours, such as neglect or hostility. Not surprisingly, both children and parents were dissatisfied with the inpatient experience.

Example of good practice – relationships with staff

“When I was transferred to Dudhope Young People’s Inpatient Unit, I was so much happier. It seemed that all of the staff understood and they ALL wanted to help me. I was still on constant observations but on the Wednesday that week, I got off them. I was a very disruptive patient whilst there, but I was shocked when nobody made fun of me, argued with me, judged me or anything like that, I had other patients come over after I had wrecked the entire place, hug me and ask “are you better now?”. The staff were amazing at deescalating my extreme violence which was very prominent, and fuelled by my equally extreme anger at the world in general. I shouted and swore at staff, refused their support after self-harming episodes and became violent with anyone who angered me.

But despite all of this, the staff stuck by me and sat and listened to me, and tried to help me (even after I’d assaulted them or worse). This is the first time in my life where someone has stuck by me after seeing all of my issues, and because of this, I learned to trust again. Trust that people do actually care, and trust that they could keep you safe whether it be from yourself or others.

…Dudhope YPU has taught me that even when other people let you down, there will be someone else you can trust. I had major attachment and trust issues, and because of my inpatient experience, I became a better person, much better able to cope with my difficulties and also able to fight for what I need, which is a stable environment.”

Excerpt taken from a young person’s experience of Dudhope Young People’s Inpatient Unit, Dundee on Care Opinion.

Some young people with the most difficult and complex emotions are treated in secure inpatient environments. NHS England has developed the SECURE STAIRS framework to support this group. The framework is based on two core elements:

- The SECURE element emphasises consistency in day-to-day care. Front line staff understand the needs of young people from an attachment/trauma perspective.

- The STAIRS element emphasises coordinated, multi-disciplinary interventions which are formulation-driven. This means that treatment is designed to address the team’s ‘formulation’, or understanding, of an individual young person’s distress.

Importantly the framework captures and supports the needs of staff as well as the young people they are looking after.

SECURE STAIRS includes the following components and desired outcomes:

- S - a staff team with the necessary skill set to meet the needs of the young people;

- E - emotionally resilient staff who are able to respond in the young person’s best interest at all times (with reduced sickness and sick leave themselves);

- C - staff who feel cared for and are enabled to provide the most helpful therapeutic environment for young people with complex needs;

- U - staff who understand psychological theory and are able to apply this to practice (via training and supervision) to enable young people reach their potential;

- R - reflective systems which improve the environment in the unit, leading to less risky behaviours, more consistency and better communication;

- E – ensuring every interaction matters and is positive.

- S - sufficient scoping for each young person to ensure comprehensive assessment;

- T – targets for the length of stay are collaboratively developed for each young person;

- A - activators for behaviours are identified as part of a comprehensive psychological formulation;

- I – interventions are informed by the formulation, are evidence-based and developed collaboratively with the aim of delivering sustained change after discharge;

- R – progress towards targets and the efficacy of interventions is regularly reviewed and revised

- S – the sustainability of change after discharge remains a key consideration throughout a young person’s stay in a secure setting, with the aim of long-term improvement of their life chances (specifically through reduced rates of reoffending; more stabile housing; better health, education, and employment opportunities; and more effective therapeutic pathways which continue as they move into adulthood and may be provided in the community)

The central relationship with ward staff, and the need for an empathetic relationship, has important implications for staff planning. There needs to be sufficient numbers of staff, deployed in a way that enables trusting relationships to develop. This is particularly important at a time when the CAMHS inpatient workforce is not growing (NHS benchmarking, 2019) and levels of reported staff burnout are high (Johnson et al., 2012).

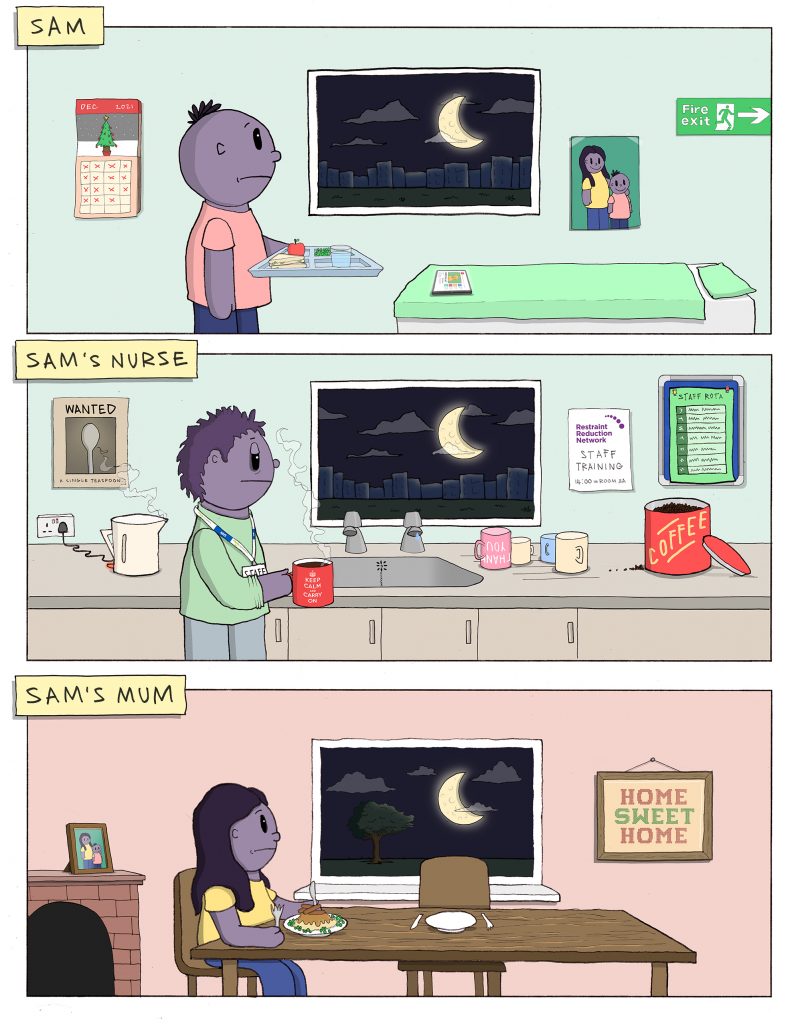

Normality

For a text description of this image please click here. In addition, you can also download this image and explanation as a PDF poster.

Lengthy admissions can dislocate a young person from the things they value most in their day-to-day lives. Inpatient settings may lack the most important aspects of ‘homeliness’, especially if there are rules or ‘blanket restrictions’ that do not take into account individual needs. Promoting a sense of normality wherever possible, through flexibility and personalised care, can significantly improve a young person’s experience and wellbeing.

An important goal of treatment for young people and their parents is to maintain or improve the ability to function normally (Ronzoni and Dogra, 2012). But, as we highlighted earlier, many children and young people are inpatients for long periods; the average length of stay is from two to nine months. This experience can dislocate them from normal life and a sense of normality.

Young people often find inpatient environments inflexible and unresponsive to their needs. They may have little choice or autonomy in an unfamiliar environment, often far removed from family, friends, and other aspects of 'homeliness' (Reavey et al., 2017). Some young people perceive that they are “living in an alternative reality” (Haynes et al., 2011). They report feelings of restriction and disconnection, and of having to use various relational and practical strategies to cope with the blanket restrictions (Haynes et al., 2011).

Normality can be promoted in several ways. Flexibility, autonomy and the capacity to exercise choice are important. Blanket restrictions should be avoided. The Restraint Reduction Network were commissioned by NHS England to carry out a project which explored the effects of Blanket Restrictions, and they have developed resources and a toolkit to address the long-term harm blanket restrictions can cause.

There is a need for age-appropriate activities (Wolpert et al., 2016). Good relationships with their peers bring many benefits, including normality, shared experience, acceptance and a sense of being cared for (Dalzell, 2019). Just being with other children or adolescents on the ward improves normality through a sense of shared experience (Grossoehme and Gerbetz, 2004).

The therapeutic relationship also includes physical aspects of the environment (Fenner, 2011). The design and decoration of units can influence satisfaction, with some needing more gender-specific facilities to protect privacy. Young people need to feel safe and comfortable (Hayes et al., 2020).

Examples of good environments

Linn Dara, Dublin (Health Services Executive): A family flat where parents and/or carers visiting from further afield can stay. This gives them the opportunity to trial arrangements for leave, and can help parents and/or carers regain confidence in caring for their child.

Ancora House (Cheshire and Wirral NHS Foundation Partnership Trust): This service in Chester comprises two units which were built with young people, for young people. The young people, ward staff and architects had open channels of communication and collaborated on everything from the colour of the walls to the furniture, mood lights in bedrooms and various quiet spaces.

Dewi Jones Unit (Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust): The food provided by the unit is home-cooked by an onsite chef and tailored to the children’s tastes. The chef embodies the ethos of person-centred care and ensures she knows the likes and dislikes of each child so that she can provide food that they will enjoy.

Newbridge House (Eating Disorders Unit in Birmingham, Schoen Clinic): All young people have personalised timetables. Occupational therapy groups are prescribed to each young person to meet their needs and choices

Fraser House, Ferndene Hospital (Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust): Young people at the unit can work towards the Duke of Edinburgh award scheme, and use their beautiful local green spaces while following the programme

Highfield Adolescent Unit (Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust) Young people can produce and record music professionally in a lottery-funded recording studio.The service also collaborates with past patients, professionals, and celebrities to produce 'Short Films About Mental Health',

Examples of good practice from the Quality Network for Inpatient CAMHS Annual Report, April 2020

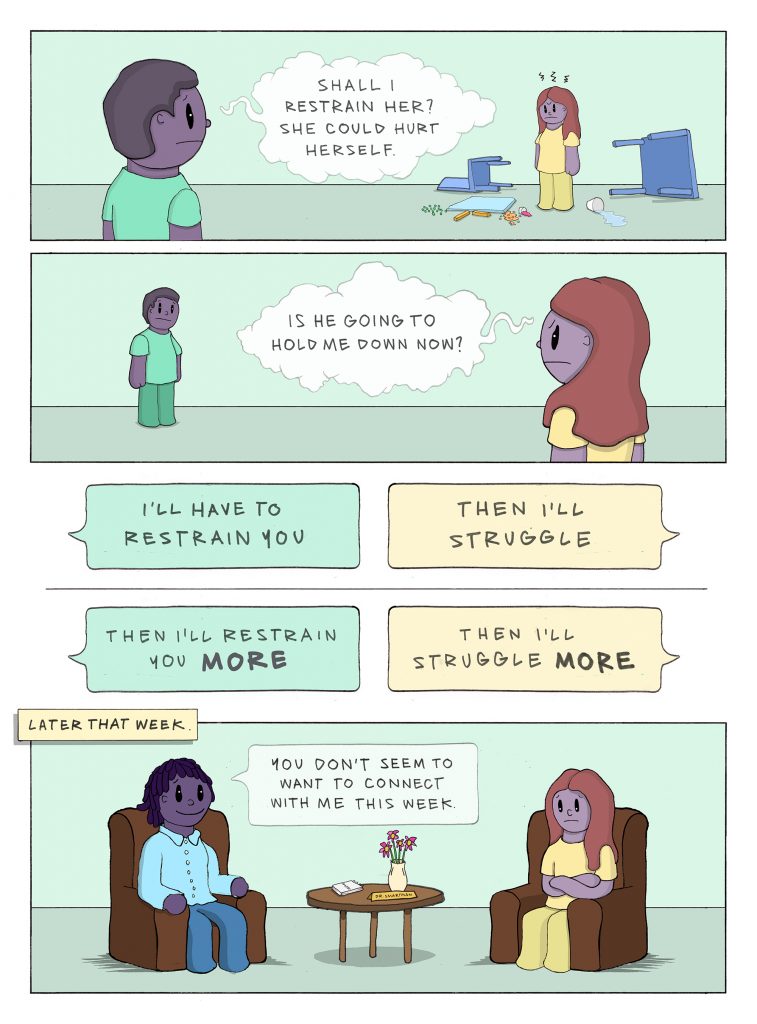

Restrictive practices

For a text description of this image please click here. In addition, you can also download this image and explanation as a PDF poster.

Physical restraint can have negative consequences for all involved and should only be used as a last resort, to prevent harm to a young person or member of staff. It can leave the young person feeling scared and may trigger memories of past trauma. This can damage therapeutic relationships and mean a young person is less likely to engage in treatment. Staff may feel guilt and regret, even when they believe restraint was necessary. High-quality staff training (adopting Restraint Reduction Network standards) and good, needs-based, care planning can avoid unnecessary use of restraint.

When young people exhibit difficult behaviours such as aggression or self-harm, staff may use physical restraint, chemical restraint (the use of tranquillising medication) or seclusion to prevent harm to young people or staff. The use of these restrictive practices can have a negative impact on both the young person and the member of staff. For the member of staff, the experience can be upsetting and trigger feelings of guilt and self-reproach (Fish and Culshaw, 2005).

If the young person has a history of being abused, it can trigger memories of past abuse (Fish and Culshaw, 2005). A report by the Children’s Commissioner in 2020 (Waldegrave and Roffe, 2020) drew attention to this and the “distressing nature of being restrained” (p8).

“Many children had either been subject to or witnessed restraint whilst being on the units. Many of the children reflected on their experience of restraint as being traumatic in itself, and triggering memories of previous trauma they had experienced.”

Children’s experiences in mental health wards, Children’s Commissioner, 2020.

A systematic review of seclusion and restraint in children and young people found that these measures are often perceived as coercive (De Hert et al., 2011). Restraint can frustrate children and make them aggressive, can reduce their trust in staff and their ability to trust in general, and can undermine the therapeutic relationship (Fish and Culshaw, 2005; Ling et al., 2015). The impact can be particularly problematic if staff are thought to be using it unnecessarily and not as a “last resort” (Fish and Culshaw, 2005).

The experience of physical restraint in learning disability and autism from Fish and Culshaw (2005): The Last Resort? Staff and client perspectives on physical intervention (clients of a medium secure learning disability service in North-West England).

Eloise: After you’ve been restrained how do you feel towards the staff involved?

Client: Nasty, you feel nasty towards them. You’re on the floor, they sit on your legs, knees on your legs, I can’t move my legs or arms. It’s hard.

Eloise: Does it help you to calm down?

Client: No, it makes me want to struggle.

Some female clients reported that the use of physical intervention can bring back memories of abuse they suffered in the past.

Eloise: So does it matter to you who restrains you?

Client: Yeah, if it’s men I go ballistic.

Eloise: Why is that?

Client: I don’t know. ‘Cause I were raped by me dad and I don’t feel that, it’s like (names clinical team leader) said that men shouldn’t restrain me. There were men on me foot and even on me hand. I turned around and said I’ll give you 3 to get off or I’ll go to (staff member) and they wouldn’t get off.

The Care Quality Commission (CQC, 2020) assessed wards for children and young people with mental health problems, a learning disability or autism. It found that four in five (81%) of the 313 wards had used physical restraint in the month before the information request. More than one in six (18%) had used prone restraint at least once in the same time period. The CQC found that staff training was patchy, particularly in relation to people with learning disabilities and autism, or those with sensory needs such as for blindness or deafness. More than half (54%) of those who had experienced seclusion had care and treatment plans that were generic and not aimed at meeting their individual needs. The Children’s Commissioner (Waldegrave and Roffe, 2020) also highlighted that good, needs-based, care planning can avoid unnecessary use of restraint.

Physical health needs, such as seizures and brain injury, were not always properly assessed or followed up, nor considered as a potential factor in people’s distress. This is not peculiar to England. Internationally, a significant proportion of young people in inpatient psychiatric care experience restraint and seclusion (Day, 2002; Delaney, 2006).

NHS England has developed a dashboard of restrictive practice. It shows monthly use of physical, chemical and mechanical restraint and seclusion or segregation, according to age, sex and ethnicity. It is still in the early stages of development and there are concerns about data quality, as not all providers are submitting data routinely. From the most recent month’s data from the dashboard, 485 young people were restrained 2,276 times.

Our steering group raised concerns about the use of seclusion, which the dashboard suggests is used in 4% of all instances of restraint. Members of the group felt the presence of a dedicated seclusion room could encourage 'practice drift' to increased use. However, they also noted that the lack of a seclusion space may increase the use of sedation and or physical restraint.

The Royal College of Psychiatrists' Quality Network for Inpatient CAMHS (QNIC) sets standards for seclusion rooms. As well as meeting safety requirements, they should be well insulated and ventilated, have natural light, direct access to toilet/washing facilities, a means of two-way communication with the team and a clock that patients can see.

Good, needs-based, care planning can avoid unnecessary use of restraint (Waldegrave and Roffe, 2020). Any member of staff who uses restraint should be appropriately trained. The Restraint Reduction Network has developed a set of training standards and provides a range of resources to help reduce the use restraint.

Expectations and outcomes

Expectations and outcomes both influence experience. Young people and their caregivers may have different expectations, including what a good outcome would be. Ronzoni and Dogra (Ronzoni and Dogra, 2012) explored expectations of CAMHS services. Overall, children, young people and their parents or carers agreed that the most important outcomes were improved symptoms of anger, anxiety, self-esteem and reduced self-harm, together with being able to function in society. However, children and young people prioritised getting a diagnosis, medication and help with education; whereas parents and carers valued their child’s safety and not having to worry about them. This was thought to reflect parents’ needs for a better quality of life and space for themselves.

Young people and their parents may have different perceptions of the experience (Solberg et al., 2015). For example, one study found that both parent and adolescent satisfaction was related to living conditions (r=0.61). But parental satisfaction was more strongly associated with the doctor (r=0.62) than young people’s (r=0.47); their satisfaction was far more associated with the nurses (r=0.74) (Marriage et al., 2001).

The outcomes of care are an important driver of satisfaction. A number of studies have found a correlation between clinical outcomes and parental satisfaction (Blader, 2006; Rey et al., 1999). Similarly, adolescents' satisfaction ratings are frequently related to outcomes (Madan et al., 2016).

Conclusion on the critical influences on experience

For a text description of this image please click here. In addition, you can also download this image and explanation as a PDF poster.

An inpatient admission is not easy for anyone involved: the young person, their family, carers, and hospital staff. Meeting everyone’s needs can be challenging. Understanding and respecting everyone’s perspective is essential to improve experience and outcomes.

Children and young people with mental health, learning disability or autism who require admission, are by definition at a vulnerable and difficult time in their life. The quality of the experience can determine whether the outcome from admission is good or bad. The eventual outcome will in turn influence how young people and their parents view the experience.

To avoid a sense of dislocation and disconnection, they need a sense of normalcy. Each child is unique, and normalcy needs to be defined in their terms, not the hospital’s. The quality of the relationships they build with their peers, with the staff that care for them and with their therapists, will all have a positive influence and help them manage their own emotions. These relationships can be undermined by poor staffing levels and the use of restrictive practices, which can trigger distress in both young people and those looking after them. Good, needs-based care can avoid unnecessary use of restraint and support more personalised care.

What is the best way to gain insight into young people's inpatient experience?

In the previous section, we described the drivers of a good outcome and experience of inpatient care for young people. Here, we explore the methods to assess whether these elements are in place. There is minimal evidence specific to children and young people's mental health and learning disability inpatient care. We therefore draw on broader evidence capturing people’s experiences of hospital and combine this with insight gained from our sense-making consultations with staff.

The different approaches to capturing experience – their strengths and weaknesses

Sheard et al. (Sheard et al., 2019) observed at least 38 different types of data collection on patient experience in the NHS. Data collection methods vary on a spectrum from descriptive (such as complaints or patient stories) to quantitative (such as surveys). The former are rich in data but staff are often concerned about generalisability. The latter are more standardised but do not capture the key elements that influence satisfaction (described earlier). More qualitative methods are therefore more likely to generate actionable and useful insight. But Weich et al. (Weich et al., 2020) found that one in five (22%) mental health Trusts were struggling to capture feedback routinely.

The specific needs of people with mental health problems and learning disability

Concerns about reliability mean that vulnerable people, such as those with acute mental health problems, are sometimes excluded from giving the formal feedback that feeds into compliance and assurance programmes. Weich et al.'s (Weich et al., 2020) study in inpatient units for adult mental health found that even the most acutely ill could give feedback, but staff often did not ask them. The quality of relationships between staff and patients affected the nature of feedback. Patients or carers would offer feedback selectively at the end of their stay and only if they had experienced good relationships with staff throughout. Sanders et al.(Sanders et al., 2020) found that people with mental health problems often said they would be unlikely to use digital methods to give feedback, especially when unwell, and they might feel unable to write. They would prefer to provide verbal feedback.

Recent work by the CQC through their "Declare your care” campaign shows that people with a learning disability are more likely to regret not complaining about poor care than those without. They are also twice as likely to have concerns about mental health services than people without learning disabilities.

The specific needs of children and young people

Children and young people with mental health issues represent a doubly vulnerable population because of their age and the stigma associated with mental illness (Mulvale et al., 2016). A 2011 study found that teenagers are more likely to give survey responses than younger children, noting that cognitively, teenagers are starting to find a sense of self, becoming more outspoken and clearer about what their needs are (Ronzoni and Dogra, 2012). Capturing the experience of children and young people in inpatient care needs to be sensitive to these differences. Techniques such as storytelling and visual media, which establish equal status among participants, are needed. Frequent breaks help, as does having skilled interviewers and facilitators. Capturing experience requires great skill and sensitivity.

Experience-based co-design (EBCD)

One narrative-based approach that can improve service is experience-based co-design (EBCD). Experiences are gathered from staff, service-users and sometimes carers via observation and interviews (which are typically filmed). 'Touchpoints' (critical experiences in relation to the service) are identified and fed back to participants, who then prioritise them. A summary (often a short film) is created and shared with staff. Staff and patients explore the findings and work in small groups to identify and implement activities to improve the service. Bate and Robert (2007) note that rich narratives of experience are not intended to be objective or verifiable but to illuminate the uniquely human experience.

EBCD has particular challenges in mental health settings. Filmed interviews need to be adapted to be shared (Boden et al., 2018). In an inpatient mental health context, service-users may have histories of trauma and abuse. Collecting experiential accounts, and sharing them with others carries a risk of re-traumatising interviewees. Issues of confidentiality and anonymity, and the legacy and ownership of recorded material, must be thought through. To address this, original experiential accounts were audio-recorded and transcribed to identify touchpoints. Service-users and carer volunteers volunteered to be filmed; the interviews related solely to the prioritised touchpoints.

Despite the success of EBCD, time and cost can be a barrier to its adoption (Locock et al., 2020). National video and audio archive of patient experience narratives can support the process. They can be used to create the touchpoints for the co-design event. The Health Experiences Research Group at the University of Oxford collects and analyses video and audio interviews with people about their experiences of illness. It has a national archive of around 3000 interviews, covering approximately 75 different conditions or topics. Selected extracts from these interviews are on Health Talk.

Capturing compliments as well as complaints

Many patients provide feedback about a good experience, but staff don't always recognise and value it. Weich et al. (Weich et al., 2020) described how patients in mental health settings often spent time thinking about the way to frame and phrase praise. However, positive feedback was often treated in an (unintentionally) dismissive way by staff. Positive feedback is plentiful but it is often not probed and positive practice that should be illuminated and encouraged is rarely identified (Sheard et al., 2019).

“I think the complaints get dealt with but there isn’t really any praise and I don’t think that’s because we’re not doing a good job, because I have parents all the time saying, “Thank you so much” and that’s fine, but It’s not collected, not audited.”

Quote from nurse (inpatient CAMHS),

Positive feedback tends to be short; often in a single word like 'fantastic'. There is a danger of giving less weight to this type of feedback (Rivas et al., 2019). Improvements as a result of positive feedback are often seen as less important and not recorded by the organisation (Donetto et al., 2019).

Conclusion on capturing experience

Capturing experience in inpatient care settings is not easy. There are barriers, both real (time and cost), and perceived (feedback reliability). There is also a potential “Catch 22”: a poor experience drives reluctance to give feedback. Using appropriate qualitative methods that address power imbalances and potential communication difficulties can provide rich insights. More research is needed on the specific needs of children with mental health needs, autism and learning disabilities. Their complex emotional needs, communication challenges and long inpatient stays all suggest particular challenges to be overcome.

How can understanding experience be used to improve inpatient care?

As in the previous section, this section relies heavily on broader evidence on service improvement. However, we have benefited from the feedback gained through our consultation with CAMHS staff.

Collecting experience data does not automatically lead to improvements. Weich et al. (Weich et al., 2020) found that more than half (51%) Trusts said they were collecting feedback but were experiencing difficulty in using it to drive change. Only one in four (27%) Trusts could describe how they use patient experience data to support change. Sheard et al., 2019, found that survey data is collected at the organisational level in some Trusts, and staff are unaware of it. This may go some way to explaining DeCourcy et al.'s (DeCourcy et al., 2012) findings that the national NHS patient survey in England has led to little change over time. The only significant improvements were in areas where there have been government-led campaigns, targets or incentives.

The literature highlights several barriers and facilitators of change.

Capacity to make sense of patient experience data

Staff want answers to specific questions about their service or particular patients rather than generalised findings. The format of feedback matters, and accessible reports, as infographics for example, are particularly helpful (Graham et al., 2018; Rivas et al., 2019). Senior ward staff are often sent spreadsheets of unfiltered and unanalysed feedback, and they may not have the skills to interrogate it. This can be made worse if staffing calculations do not factor in the time to reflect and act on patient feedback (Sheard et al., 2019). When frontline staff (often nurses) have the right skills and the necessary time, they can use imperfect data, set it in context and search for further data to fill gaps. They can use the evidence to improve services (Donetto et al., 2019).

Staff looking at multiple sources of feedback, coupled with their own ideas of what needs to change, can support 'knowledge in practice' (Locock et al., 2020). In a process akin to 'clinical mind lines', as described by Gabbay and Le May (Gabbay and le May, 2004), understanding is informed by a combination of evidence and experience.

Missing the insight offered by complaints

'Experience' and 'complaints' are often dealt with by different teams. This leads to missed opportunities to use feedback from complaints to improve care for future patients (Locock et al., 2020).

The capacity and authority to take action

For staff to believe listening to patients is worthwhile, they need the authority and resources to make changes based on their feedback (Sheard et al., 2019). (Donetto et al., 2019). This is particularly true when improvement requires a change in the organisation's policies and procedures. Ongoing commitment from senior staff is important (Graham et al., 2018). And multidisciplinary changes are difficult unless teams are already working together in this way (Sheard et al., 2019).

“I just think the ward and leadership style feel quite psychologically safe for our team. And we’ve worked really hard to get to that. I think this is at all levels, from junior staff up to our directorate senior leadership actually. I think if a team feel psychologically safe within their team to say I don’t think this is right, or is there any way we can change this, then I think they will do so and the concerns are escalated and can be acted on as necessary”

Ward Manager, inpatient CAMHS unit

The importance of allocating time and resources to capture and act on experience was emphasised in our consultations with CAMHS inpatient staff. We heard of a unit which had a dedicated member of staff (separate from nursing and care staff), with allocated time, capacity and authority to act. This member of staff was pivotal to responsive engagement with young people and their carers. The Trust’s investment in such a role allowed the unit to move above and beyond simple feedback mechanisms. It nurtured a sense of partnership between the team of staff, young people and their carers and led to continuous improvement.

“Having somebody like a HOPPI [Head of Patient and Parent Involvement] who takes leadership and ownership, helps keep it always on the agenda ... I think if I didn't have our HOPPI emailing me saying’ “You know the kids have said this, the kids have said that”: it wouldn't constantly be on my agenda. What I think is really important is not that we're just gathering pages and pages of data: it’s that we're actually using it to improve our service and to look at things where we're not improving, or where we’re deteriorating.”

Ward Manager, inpatient CAMHS unit

A preference for quick fixes and environmental change

There is a tension between quick wins and more complex improvements which require the resources to make cultural changes to enhance trust and relationships (Sheard et al., 2019). A systematic review in 2016 found that patient experience data were largely used to identify small incremental improvements that did not require a change in staff behaviour (Gleeson et al., 2016). Weich et al (Weich et al., 2020) contrasted 'environmental' change (to the physical environment or tangibles like diet, seating areas, temperature control and the physical environment of the ward) with 'cultural' change (to relationships with patients including feelings of respect and dignity, and staff attitudes).

Emotional impact on staff

The emotional impact on staff is often forgotten. Responding to patient experience can be emotionally difficult (Sheard et al., 2019). Mental health nurses experience conflict between getting to know and care for their patients while also having to sometimes control them (Gray and Smith, 2009). The seminal paper by Menzies (Menzies, 1960) describes how nurses cope with tension, stress and anxiety by depersonalising their relationship with patients. While this occurs in other professions, nurses have continuous contact with their patients and do not have non-contact time to recover.

The nature of this dynamic was revisited (Smith, 2002) using Hochschild's 1983 theory of emotional labour. Emotional labour is often invisible and unrecognised. Presenting patient experience feedback on culture, relationships with patients and staff attitudes requires sensitive handling. There is a risk of increasing emotional labour and further depersonalising the delivery of care. This is never a reason to ignore patient experience, but employers need to manage it sensitively to promote improvement rather than judgement.

Conclusion on service improvement

Collecting data on experience does not automatically lead to improvements in care. Ward level staff need the time, skills and authority to act on the data. It can be particularly hard for them to recognise the need for cultural change, and to embrace it. Change requires ongoing commitment from senior leadership.

Overall conclusion

Young people who require specialist inpatient care for mental health problems, learning disability, or autism are some of the most vulnerable and at-risk in the community. The quality of their experience is important for their short and long term wellbeing. This in turn has a significant impact on those that care for them.

The Specialist Taskforce set out its ambition that:

“The voice of children and young people, and their family or carers, are embedded in the culture of care, and are taken on board in all decisions about the care that they receive.”

This Themed Review has explored the inpatient experience of children and young people with mental health problems, learning disability or autism. We have identified three key action points to support the Taskforce’s ambition, and to address this significant area of need.

- Recognise the interdependence of experience, treatment outcomes, and other factors

First, each young person’s experience is unique. Understanding the key influences on a young person’s experience is the foundation of any improvement strategy.

We identified four broad themes: the quality of relationships between young people, their parents/carers and staff, the degree of normality of the experience, the use of restrictive practices, and good clinical outcomes. The four are interrelated; a young person is unlikely to feel they have had a good experience of care unless all factors are present. These four themes could be a useful starting point for staff on CAMHS units to develop methods to capture and monitor a more nuanced understanding of “What matters to you?”.

- Promote timely identification and action to address unmet needs

Second, it is important to use appropriate methods to capture the experiences of young people and their parents/carers/advocates in real-time. This will alert staff when the needs of individuals are not being fully met. It will give them the best chance to identify, intervene and improve the experience. Young people, their parents/carers and staff, all benefit when experience is acted on in the ‘now’ and not delayed due to feedback systems. Our Themed Review has highlighted an evidence gap in this area. More work is needed to identify the approaches most appropriate for the CAMHS inpatient setting.

- Equip staff with the resources, capacity and authority to improve experience

Third, improving experience is not a straightforward exercise. An individual member of staff can undoubtedly have a positive effect on the experience of a young person. But improving experience more widely is rarely in their gift. This can be due to several factors, such as their access to and ability to interpret data, resources (both physical and emotional), capacity, and authority. Different moving parts in the system need to align to create apparently small changes; the general evidence on improvement suggests that with the appropriate leadership and collaboration, this can be done. More research is needed in a CAMHS inpatient setting but staff could improve young people’s and their carer’s experience of inpatient care. Investment in roles with protected time, appropriate resources, improved capacity and authority to act will all be needed for this to happen.

We are continually trying to better understand the views and needs of our audiences, and make improvements in the way we share knowledge. We would love to hear your thoughts and reactions to this style of dissemination via our brief online survey.

Illustrations

You can download all the illustrations in this review as a PDF booklet. In addition, we have produced individual posters of each panel. You can find the links for these below:

- Full PDF booklet

- Posters

This report was written by Jodi Brown (NIHR), Candace Imison (NIHR) and Shaun Liverpool (Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families, University College London).

The Themed Review was guided by a Steering Group, listed below, led by Dr. Elaine Maxwell (Clinical Advisor, NIHR).

We are grateful to the young people, parents, carers and staff who participated in our sense-making exercise and to the members of our Steering Group who gave their time and experience to shape this Themed Review:

Dr. Paul Abeles – Consultant Clinical Psychologist: Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust

Dr. Roger Banks – National Clinical Director, Learning Disability and Autism: NHS England and NHS Improvement

Dr. Gill Bell – Consultant Forensic Adolescent Learning Disability Psychiatrist: Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust

Ruth Cooper – Operational and Strategic Lead for Learning Disability: East London NHS Foundation Trust

Dr. Rachel Elvins – Consultant Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist: Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust

Teresa Fenech – Director of Nursing & Quality Improvement Taskforce Director (CYPMH, LD and autism inpatient services): NHS England and NHS Improvement

Emily Frith – Head of Policy and Advocacy: Children’s Commissioner’s Office

Dr. Sarah Knowles – Knowledge Mobilisation Research Fellow: The University of York

Dr. Katrin Lehmann – Clinical Nurse Specialist CAMHS: Belfast Health and Social Care Trust

Funmi Osowumni – Parent Representative: Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families

Dr. Sara Ryan – Mother and Campaigner ‘Justice for LB’; Professor of Social Care, Manchester Metropolitan University

Leanne Walker – Expert by Experience; Patient and Public Voice Member: NHS England CAMHS Clinical Reference Group; Patient Representative: The Royal College of Psychiatrists

Smith, P.C., 2002. Performance management in British health care: will it deliver? Health Aff. (Millwood) 21, 103–115.

Solberg, C., Larsson, B., Jozefiak, T., 2015. Consumer satisfaction with the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service and its association with treatment outcome: a 3-4-year follow-up study. Nord. J. Psychiatry 69, 224–232.

Tas, F.V., Guvenir, T., Cevrim, E., 2010. Patients’ and their parents’ satisfaction levels about the treatment in a child and adolescent mental health inpatient unit. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 17, 769–774.

Tulloch, S., Lelliott, P., Bannister, D., Andiappan, M., O’Herlihy, A., Beecham, J., Ayton, A., 2008. The Costs, Outcomes

Smith, P.C., 2002. Performance management in British health care: will it deliver? Health Aff. (Millwood) 21, 103–115.

Solberg, C., Larsson, B., Jozefiak, T., 2015. Consumer satisfaction with the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service and its association with treatment outcome: a 3-4-year follow-up study. Nord. J. Psychiatry 69, 224–232.

Tas, F.V., Guvenir, T., Cevrim, E., 2010. Patients’ and their parents’ satisfaction levels about the treatment in a child and adolescent mental health inpatient unit. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 17, 769–774.

Tulloch, S., Lelliott, P., Bannister, D., Andiappan, M., O’Herlihy, A., Beecham, J., Ayton, A., 2008. The Costs, Outcomes

Smith, P.C., 2002. Performance management in British health care: will it deliver? Health Aff. (Millwood) 21, 103–115.

Solberg, C., Larsson, B., Jozefiak, T., 2015. Consumer satisfaction with the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service and its association with treatment outcome: a 3-4-year follow-up study. Nord. J. Psychiatry 69, 224–232.

Tas, F.V., Guvenir, T., Cevrim, E., 2010. Patients’ and their parents’ satisfaction levels about the treatment in a child and adolescent mental health inpatient unit. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 17, 769–774.

Tulloch, S., Lelliott, P., Bannister, D., Andiappan, M., O’Herlihy, A., Beecham, J., Ayton, A., 2008. The Costs, Outcomes and Satisfaction for Inpatient Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Services (COSI-CAPS) study. National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R&D.

Waldegrave, H., Roffe, J., 2020. Children’s experiences in mental health wards. Children’s Commissioner.

Weich, S., Fenton S-J, Staniszewska S, Canaway A, Crepaz-Keay D, Larkin M, Madan J, Mockford C, Bhui K, Newton E, Croft C, Foye U, Cairns A, Ormerod E, Jeffreys S. & Griffiths F, 2020. Using patient experience data to support improvements in inpatient mental health care: the EURIPIDES multimethod study. Health Serv. Deliv. Res. 8.

Wolpert, M., Jacob, J., Napoleone, E., Whale, A., Calderon, A., Edbrooke-Childs, J., 2016. Child- and Parent-reported Outcomes and Experience from Child and Young People’s Mental Health Services 2011-2015. Child Outcomes Research Consortium, London

NIHR Evidence is covered by the creative commons, CC-BY licence. Written content and infographics may be freely reproduced provided that suitable acknowledgement is made. Note, this licence excludes comments and images made by third parties, audiovisual content, and linked content on other websites.